How a Maverick Hip-Hop Legend Found Inspiration in a Titan of American Industry

When LL COOL J sat for his portrait, he found common ground with the life-long philanthropical endeavors of John D. Rockefeller

:focal(800x342:801x343)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c9/55/c955d27c-ae62-43b5-bb88-8a24670a393d/ll_cool_j.jpg)

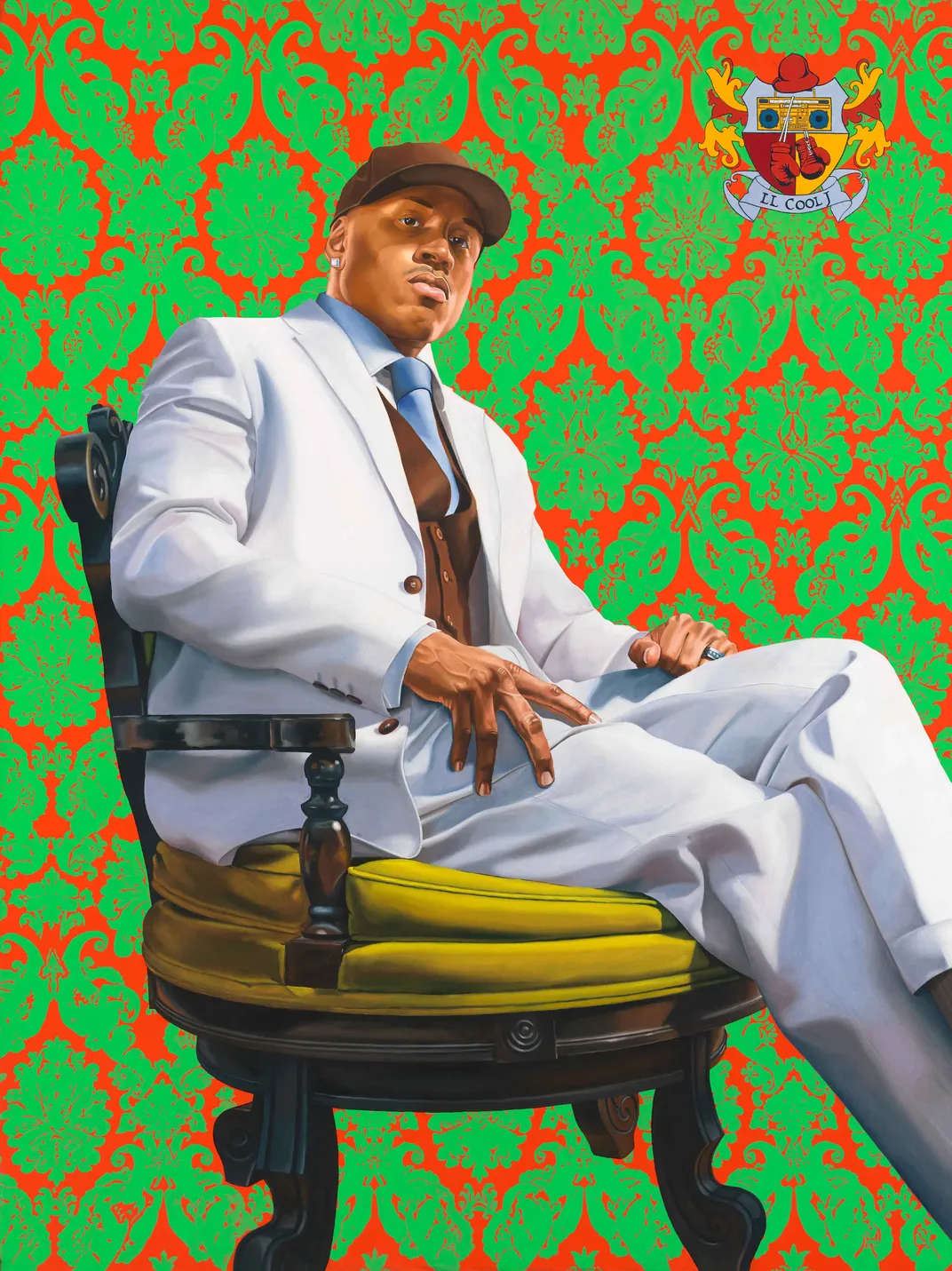

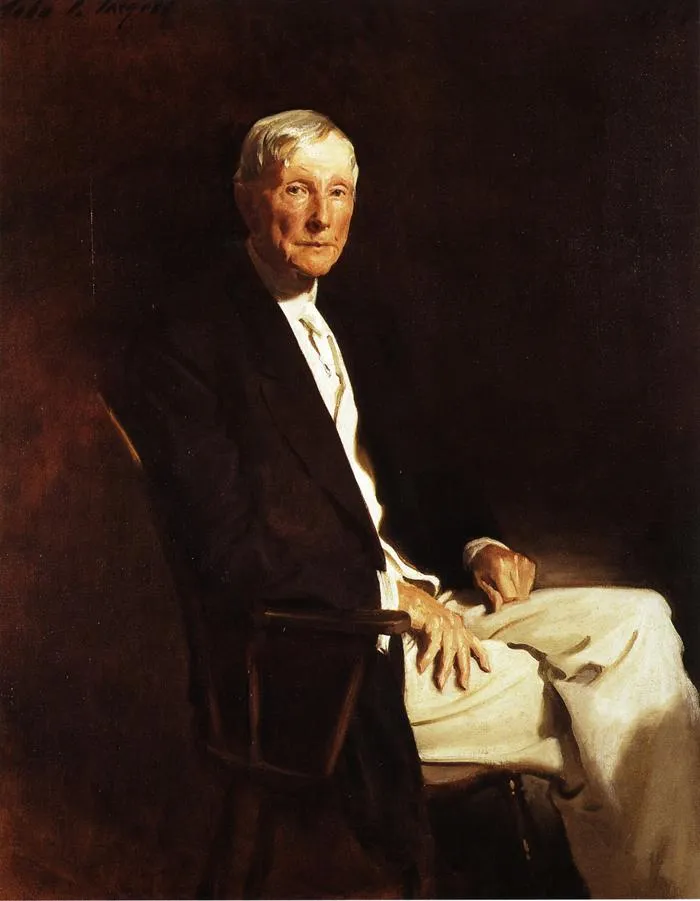

When LL Cool J prepared to pose for a portrait by a renowned artist, he looked to tycoon and philanthropist John D. Rockefeller for inspiration. As the rapper and actor met with the artist Kehinde Wiley, he had an image in mind—John Singer Sargent’s portrait of Rockefeller. Wiley has captured many visages, including Barack Obama’s portrait, that are held in the collections of the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery. Using historical works as a starting point, Wiley creates artwork that is very much a style of his own.

Growing up in Bay Shore, Long Island, LL found solace in hip hop music, having witnessed at the age of 4 his father shoot his mother and grandfather. Later, he suffered abuse at the hands of his mother’s boyfriend. At age 9, he was already writing his own lyrics and by 17, his first album by Def Jam had been released. By the time he was 30, LL had become the Rockefeller of the entertainment world with two Grammy awards, two MTV Video Music Awards, including one for career achievement, published his autobiography and launched an acting career. Today, he is the star of the popular television series NCIS: Los Angeles and one of the most sought-after host for award shows. In 2017, he became the first rapper to win recognition at the annual Kennedy Center Honors. In 2019, he took a seat on the Smithsonian National Board.

Shortly before his sitting for the portrait, which now hangs in the Portrait Gallery opposite a painting of author Toni Morrison and near one of Michelle Obama, LL had read a biography of Rockefeller. He was impressed by the business acumen of the man who was once one of the richest people on Earth, and he was struck by Rockefeller’s philanthropic legacy after donating more than $500 million in his lifetime.

The rapper spoke with the museum’s director Kim Sajet and the renowned British art historian Richard Ormond joined in the discussion, sharing his thoughts as part of the podcast series, Portraits. The segment is entitled “The Rockefeller Pose.”

Listen to "The Rockefeller Pose"

with LL Cool J and art historian Richard Ormond

As the foremost portraitist of his time, Sargent painted Rockefeller in 1917, about seven years after he had turned away from portraits to concentrate on painting landscapes. Ormond, who is Sargent’s grand-nephew and an expert on his work, says Sargent made the shift from portraits because of “the strain of being at the top of the tree. . . . Each time, you’ve got to go one better, one better.” However, when a Rockefeller son sought a portrait of the man who turned Standard Oil into an empire, the artist reluctantly agreed because he considered Rockefeller a visionary. In his portrait, the corporate czar sits in a chair with one hand splayed and the other clenched. Sajet suggests that one represents the tight-fisted businessman, while the other is open as if in the act of giving through philanthropy, and Ormond agrees. Sargent gave his $15,000 commission for the portrait—equivalent to more than $300,000 in 2020 dollars—to the American Red Cross as soldiers fell on the battlefields of World War I.

Wiley depicts LL Cool J in a similar pose; but there the similarity between the two images ends. While the elderly Rockefeller appears against a dark field, the middle-aged rapper and actor is pictured before an eye-catching pattern. Ormond says that Wiley’s background “leaps out at you” and “causes my eyes to vibrate.” Nevertheless, Ormond sees the portrait as “a power image.”

A family crest, which Ormond calls “a very witty touch,” is topped with a Kangol knit cap, one of LL’s trademarks. It also contains boxing gloves to represent his hit, “Mama Said Knock You Out,” and his family’s history in boxing. (His uncle, John Henry Lewis was the first African American light heavyweight champion.) Centrally located is the image of a boombox, which LL says “symbolizes all things that hip-hop was and is. The music that came out of the boombox was timeless and classic.” This is not “a faux European crest,” says the rapper. “That thing is very real.” It represents both James Todd Smith, the artist’s original identity, and his pseudonym, which he adopted when he was 16. It stands for “Ladies Love Cool James,” and over the years of his career, women have remained the heart of his fan base. “Men are little more than chaperones” at an LL Cool J performance, the New York Times has reported.

Ormond, who had never heard of LL Cool J before seeing this painting, says that “it’s only recently that I really got hip with rap.” After viewing the portrait, he sees the work as Wiley’s “challenge across time” to Sargent. He credits the young and successful artist with “appropriating the great tradition of portraiture, which is what the Rockefeller comes from.”

Wiley is well known for placing young African American men and women in scenes that are somewhat regal and European in origin. Because of a visit to a museum in his youth and his sense of underrepresentation of blacks in art, “there was something absolutely heroic and fascinating about being able to feel a certain relationship to the institution and the fact that these people happen to look like me on some level,” he says on his website. “One of the reasons I’ve chosen some of these zones had to do with the way you fantasize, whether it be about your own people or far-flung places, and how there’s the imagined personality and look and feel of a society, and then there’s the actuality that sometimes is jarring, as a working artist and traveling from time to time.” He seeks to lead his audience away from preconceptions about African Americans.

When LL saw Wiley’s finished portrait, which had been commissioned in 2005 by the VH1 Hip-Hop Honors, he “was blown away.” Consequently, he bought it himself and hung it in his living room. After a while, he found its overwhelming size—103 inches by 80 inches in its frame—created a problem. He questioned whether it reflected too much ego and asked himself, “Do I really want to do this to my family right now?” He wondered, “Should I light a candle and pray to myself?” He said he was fortunate that at about that time, the National Portrait Gallery approached him about a loan of the painting, which he happily granted.

He likes the connection to Rockefeller and says you “can take inspiration from anyone.” He adds that “I just like the idea of someone totally maximizing their potential on every level.” He especially liked learning that Rockefeller, a devout Northern Baptist, tithed, giving one-tenth of his income to his church—a practice LL also has adopted.

He sees Rockefeller’s story as being about “making your dreams a reality and realizing that your dreams don’t have deadlines and never denying yourself the opportunity to dream and then go after it. You’ve got to be fearless. I don’t see any reason to limit myself in America. It’s not as easy as a black man. It’s a lot more challenging, but you can still take inspiration from anyone.”

LL recalls the day he sat for his portrait and admits, “Quite honestly, Kehinde was like an alien to me—like from a whole other planet.” LL felt that he was “in my hip-hop world. I’m just fully immersed in it,” while Wiley is a “really, really, really formally educated, top-tier kind of artist with a perspective and a point-of-view.” In contrast, he says, “I’m this hardscrabble get-in-where-you-fit-in, figure-out-a way-to make-it-out, roll-up-your sleeves kind of guy.” Despite his own initial uneasiness, the rapper says that Wiley got right to work, putting him in a chair and spending four to five hours sketching him and beginning his portrait.

One of LL’s recent works is a rap song on Black Lives Matter and George Floyd’s death. Because the campaign has led to removal of Confederate statues in the South and imperialist images elsewhere, he says, “I see the toppling of a paradigm.” He believes many Americans and others around the world finally said, “Enough is enough!” He says he does not really understand prejudice toward African Americans because it seems to be anger over the black refusal to serve as slaves. He says hatred of blacks has been passed from generation to generation. He quotes the Nobel Prize-winning Bengali poet Rabindranath Tagore in saying, “Power takes as ingratitude the writhing of its victims.”

LL says, “Racism is not a successful formula.” His new Black Lives Matter recording declares that “being black in America is like rolling a pair of dice,” and that “America is a graveyard full of black men’s bones.” Nevertheless, he is hopeful. He says that “people are inherently good.” Looking back at U.S. history from Frederick Douglass to Martin Luther King Jr. to Barack Obama, he acknowledges there has been “incremental progress.” Social unrest, he says, is understandable. “When you see your people killed over and over and over again with no justice, with no remorse, with no respect, that’s bound to happen.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alice_George_final_web_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alice_George_final_web_thumbnail.png)