A Curator’s College Find Is Revisited in the New PBS Showcase ‘Civilizations’

Debra Diamond’s story, says the show’s producer, exemplifies the ‘joy of discovery’ in a whole new way

:focal(926x380:927x381)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c8/a2/c8a2b571-1b02-4619-a2b0-ebba9197565b/39750037651_c909bca9a2_k.jpg)

Nearly a half century since it first aired, under the name “Civilisation,” hosted by Kenneth Clark, public television’s cultural series is back—with the plural “s” added to its name to emphasize a far wider scope.

Rather than being hosted by a central figure, “Civilizations,” as it is being called, will be hosted by a range of cultural experts when it begins on PBS April 17. And amid the familiar triumphs of the world will be new discoveries—and certainly new connections made between the influence of East and West.

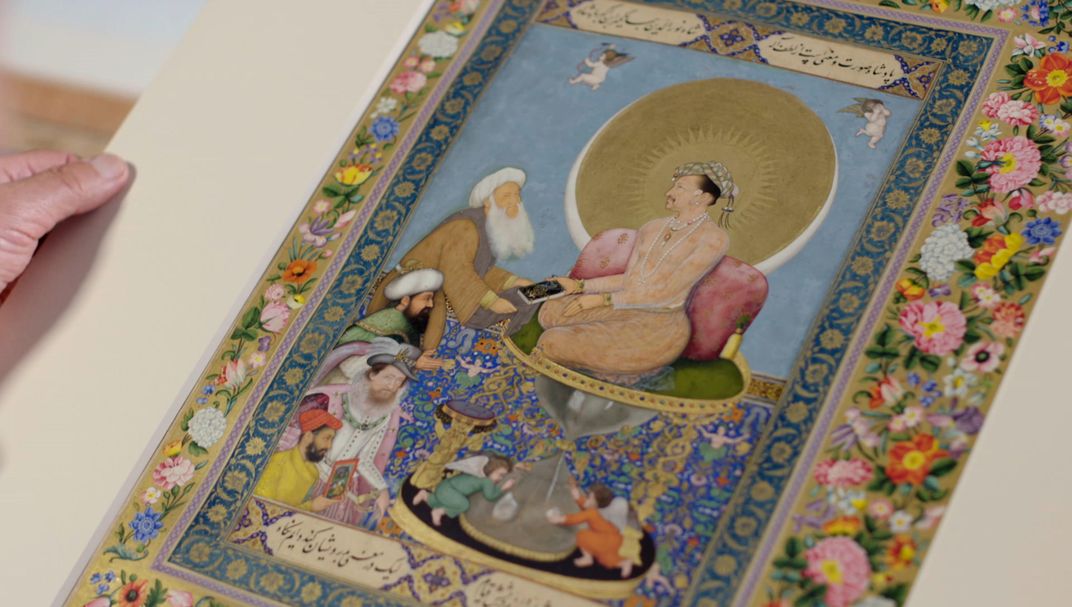

One such find was made during the college days of Debra Diamond, the curator of South and Southeast Asian Art at the Smithsonian’s Freer and Sackler Galleries. At a January press conference for the TV Critics Association winter press tour, Diamond saw the highlights clip that featured one of her own discoveries.

“There was a very gold painting from India, a detail from a huge painting circa 1810 of a yogi,” Diamond told the assembled crowd. “And nobody knew that those large paintings from that state in Rajasthan, that kingdom in Rajasthan, existed until the 2000s.”

Jane Root, executive producer of the nine-part series, wouldn’t let Diamond get away without telling the full story. “You have to say that you were the person who brought that knowledge,” she told her.

“Right. I found them in a palace,” Diamond explained. “They’re, like, my babies.” They were found in Rajasthan, in Northwest India, when Diamond was a graduate student at Columbia, where she received a PhD in South Asian history in 2000. At the time, Diamond says she was writing her “dissertation, going around, studying Indian painting and looking for a topic.” While doing so, she says, “I talked my way into the basement of a palace.”

While looking around in the basement of the Maharaja’s Fort in Jaipur, “there were these huge boxes filled with these paintings—I mean, big like coffee table size. And a lot of them that looked like color field paintings, what I was used to from growing up in the 1970s, and these vast fields of gold.”

“They didn’t look like anything I had ever seen,” she says, “and nobody had published them, certainly.” Excited, Diamond return to the U.S. and shared pictures she'd taken of her find with older art historians who did not share her enthusiasm. “They said, ’Those are hideous paintings!’”

She was undeterred. “And I persevered,” she says, “partly because they have a lot to do with yoga and I was quite interested in yoga,” who curated the wildly popular 2013 exhibition "Yoga: The Art of Transformation."

“And so it just turned out that, for 40 years, in the early 19th century, in the period when everyone thought that Indian artists weren’t doing anything because they had been quashed by the British, there was a school of some 20 or 25 artists who made hundreds, actually over a thousand, paintings of monumental size on the themes of yoga and Indian philosophy,” she says.

But, she says, “because they were considered to have been made in a decadent period, they were stuck in boxes and put in the basement of a palace.”

They emerge again in the new series. Root says, “It’s that kind of detail and that kind of story which is at the heart of “Civilizations,” that you see just the joy of discovery in a whole new way.”

“There’s new discoveries, new scholarship, and also new dimensions of filmmaking,” Diamond says of the series. “I know we’ve all seen drone photography, but, man, the footage inside buildings that you wouldn’t ordinarily have access to, or the way that old Mughal Lahore Fort looks like when the camera is flying over it, it’s really spectacular.”

It’s the same technology used to compare structures of Ottoman architect Mimar Sinan who designed the Süleymaniye Mosque in Istanbul with Michelangelo’s plans for St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome. “It’s brilliantly filmed,” Diamond says. “I mean, these structures look vast and as if they are floating in space.”

But what they are conveying in the comparison between the two is just as important. “This is the first time I had heard in a nonacademic setting Renaissance Italy compared to Turkey,” she says. “It’s very exciting that the [Renaissance] episode begins first in Istanbul before it goes to Italy and then the great Mughal Empire of India.”

It reflects, says David Olusoga, a British-Nigerian historian and writer, how “our view of the Renaissance has enormously expanded from being a North Italian phenomenon to being a Mediterranean phenomenon stretching up into northern Europe.”

In Civilizations, the Renaissance has been “extended into the Ottoman Empire, showing how Italian artists were commissioned by Ottoman sultans, as well as how the Ottoman ideas moved into Italy and moved into northern Europe,” he says. “I think that is appropriately groundbreaking, because it is the fruits of 50 years’ more thinking, reading, and seeing the world more interconnected.”

Olusoga is one of three chief hosts in the BBC co-production, along with Simon Schama, art historian and professor of history and art history at Columbia University and Mary Beard, professor of classics at the University of Cambridge.

“There is an enormous broadening of the canvas here,” Root says. “What Kenneth Clark was doing in his amazing, wonderful series was looking at one civilization and really focusing in on that. But here in the 21st century, we’re saying one of the incredible stories is many different civilizations interconnecting with each other.”

In addition to studying landscape scrolls of classical China, Olmec sculpture, African bronzes, Japanese prints and French Impressionist paintings, there is input from contemporary artists, ranging from Damien Hirst and Kehinde Wiley to El Anatsui and Kara Walker.

When the first BBC-produced “Civilisation” aired stateside in 1970, it was a landmark for many reasons, according to Beth Hoppe, chief programming executive at PBS. Not only was it the first BBC production to run on the fledgling network, Hoppe says, “it planted a flag for PBS in establishing our mission to present the very best arts programming found anywhere on television.”

After first airing on BBC in 1969, where it was a sensation, it showed in Washington, D.C. in screenings that were overrun for their popularity at the National Gallery of Art . “It was at the height of the Vietnam War marches,” Root says, “An enormous number of people queued up to see it.”

PBS acquired it because of the interest “and it became this incredible phenomena that was, really, at the very heart of PBS’s beginning. At that time, Richard Nixon, who was president, was making noises about defunding this little nascent organization, this little beginning thing that didn’t really need to exist, and “Civilisation” was one of the things that meant that that didn’t happen,” adds Root.

Since then, she added, the BBC and PBS became “the biggest makers and producers of arts programs anywhere in the world.”

‘Civilizations’ premieres April 17 at 8 p.m. on PBS (check local listings) and runs the next four episodes Tuesdays through May 15. Four more episodes air in June.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)