How Can Museums Democratize Portraiture?

As the National Portrait Gallery turns 50, it is asking how well its collections represent the people—and where there is room for improvement

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/94/12/94120c68-ec8a-4303-b96a-97318fdf54c6/114_mooney_fig_4_muse_and_carpenter.jpg)

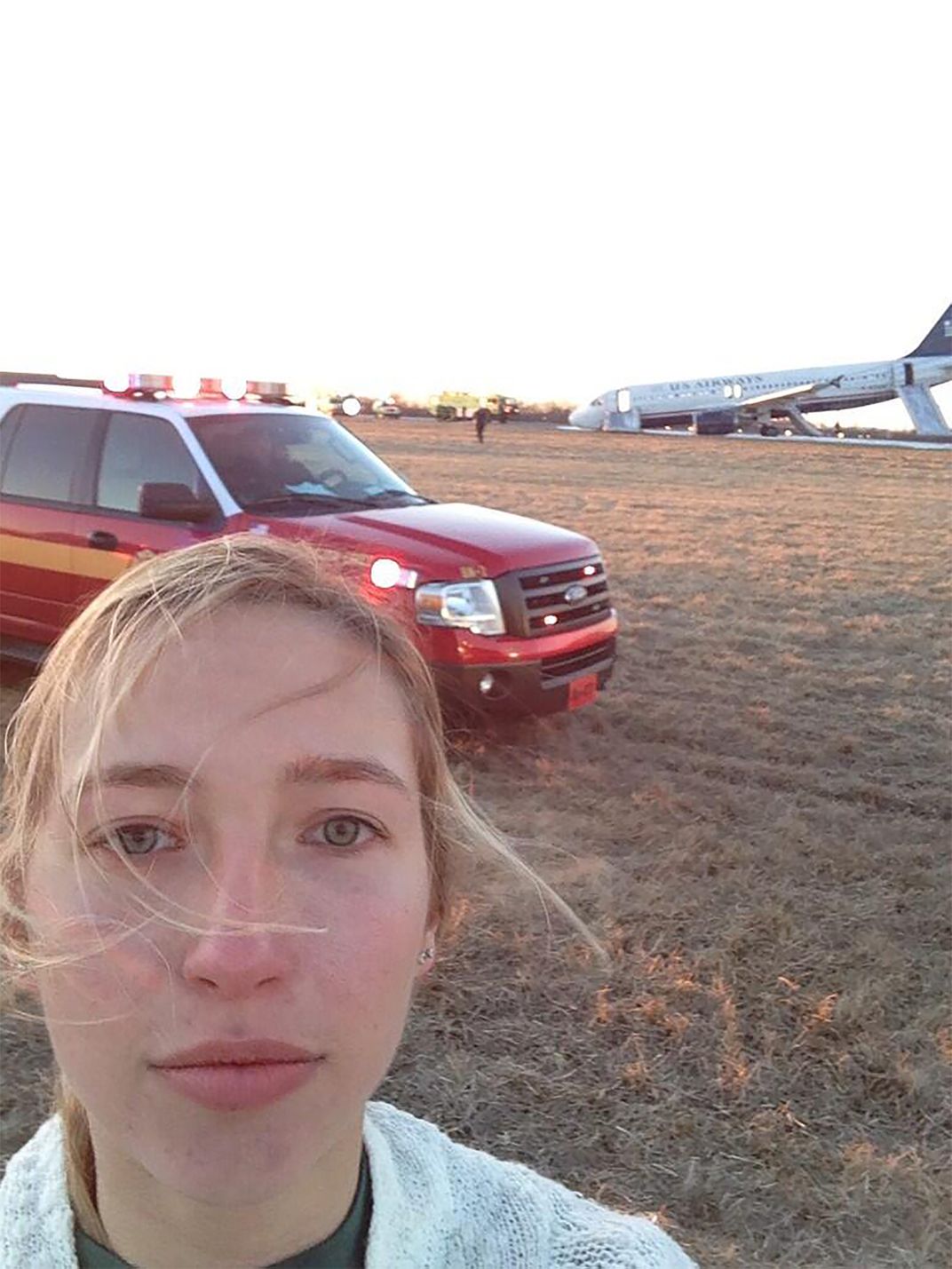

Nowadays, Americans capture photos of their friends, loved ones and selves with such regularity that the notion of smartphone “portraiture” is likely to sound absurd. “Portraiture” evokes stately oils like the Lansdowne George Washington by Gilbert Stuart—not the eclectic mementos preserved in the hard drive of your iPhone. Yet the image that graces the cover of the National Portrait Gallery’s latest book, Beyond the Face: New Perspectives on Portraiture edited by Wendy Wick Reaves, is not a regal or presidential image, but a humble selfie captured by a young American woman.

Taken on a windblown airstrip, the improvised portrait was a way of signaling to the subject’s parents that she was not harmed in a U.S. Airways plane crash (the wreck looms over her left shoulder). Circulated widely on social networks in 2014, the image prompted heated exchanges over propriety. Now, the intimate still sets the tone for a profusely illustrated, boundary-pushing scholarly examination of the essence of American portraiture and its evolution over time.

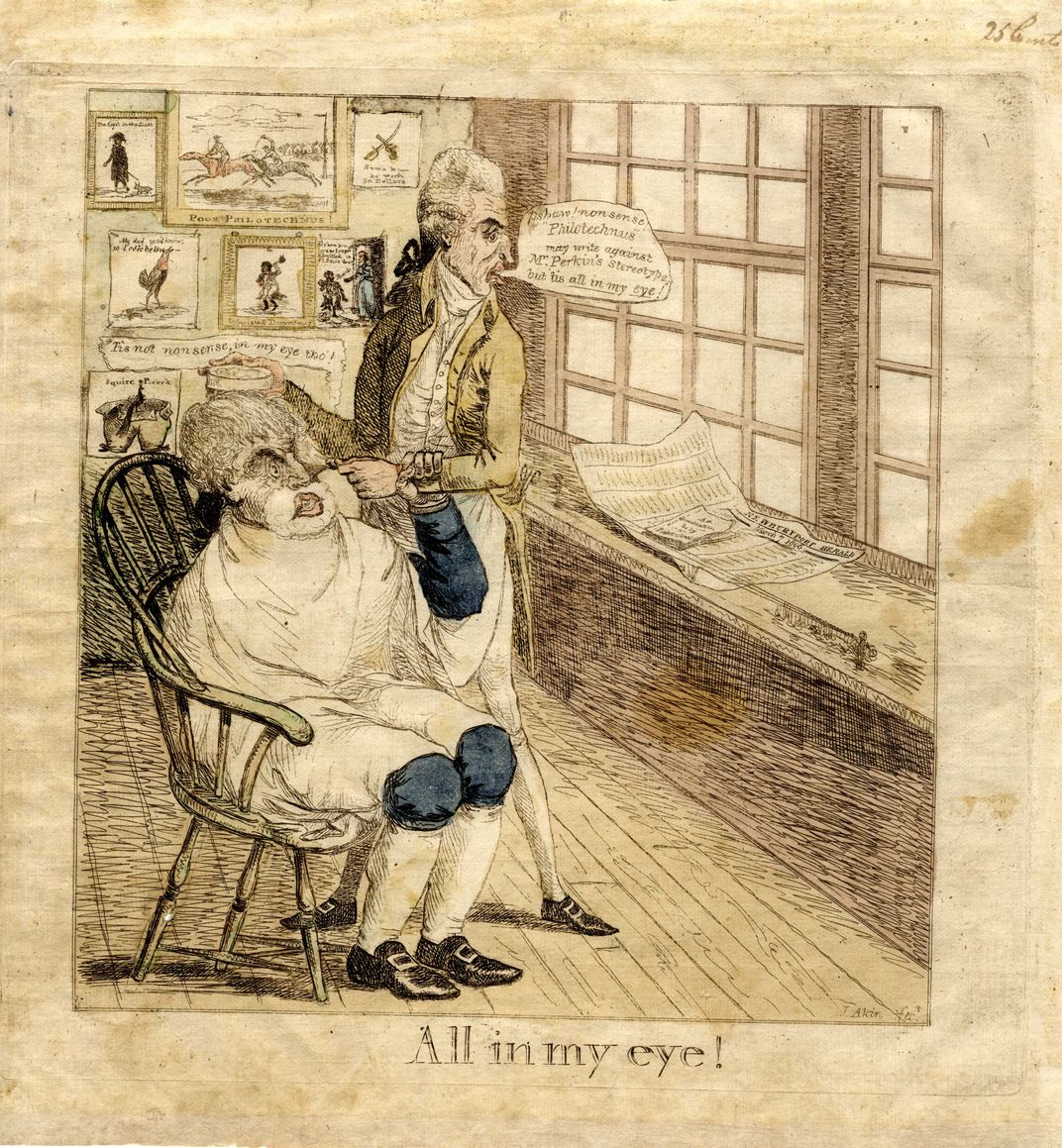

Essays from an assortment of academic portrait experts, including the University of Delaware’s Jennifer Van Horn, the University of Georgia’s Akela Reason, and Wellesley College’s Nikki A. Greene, aim to bring portraiture to the people, showing how evocative images can be appropriated and re-contextualized to fuel social movements, and how seemingly crass variants on portraiture—ranging from newspaper caricature to the modern selfie—have often had the greatest lasting effects on American history.

Beyond the Face is slated for release on September 20 of this year, and its interrogation of portraiture will be expanded upon in an unprecedented symposium to be held at the Gallery’s McEvoy Auditorium from September 20 to 21. In keeping with the inclusive thrust of the new scholarship, the event will be open to the general public.

For symposium co-organizer (and Beyond the Face essayist) Kate Clarke Lemay, 2018, the year in which the Portrait Gallery turns 50, is the perfect occasion on which to reflect critically and reevaluate the role of portraits in a changing nation. “It’s almost like a ‘state of the field’ of portraiture,” she says of the symposium, “and the Portrait Gallery has the most cutting-edge collection of portraiture in the United States”—some 23,000 artworks strong.

Even so, Lemay says the Gallery and its collections have plenty of room for improvement, and she is sure the views of both outside scholars and the general public will be invaluable in reshaping the museum’s mission in the coming years. Noting the difficulty of avoiding “hierarchies instated by the objects themselves” when putting together historical exhibitions about people whose representation in portraiture was skewed by the discrimination of their era (black women’s suffrage activists, for instance, are severely underrepresented in the portrait corpus), Lemay endorses a sustained push to keep the Gallery as inclusive as possible moving forward.

Paralleling the loosely chronological structure of the book, the symposium will address in discrete segments the formal profession of portraiture, the dissemination of portraits, the public’s role in morphing and enlivening portraits, and the ongoing expansion of the definition of portraiture.

Lemay hopes the jubilee discussion will encourage the American public to scrutinize not only the portraits on the walls, but also—using those portraits as mirrors—itself. The study of portraiture “is a great tool to reflect upon American identity,” she says, “and what that really even means.”

Amid the current debates roiling public discourse, Lemay believes that a balanced inspection of the images that resonate with us is a perfect way to confront sensitive issues productively. “There are some tricky topics that [the featured artists] have addressed,” she says, including “issues of race, issues of gender. And it’s always nice to get into those topics—which have so much meaning for so many different people—through an art object.”

The use of art objects, she says, is an effective way to catalyze dialog. “You’re talking about an object someone else made,” she says, “but you can use that object to query and explore different ideas or issues that otherwise might have felt too loaded or tricky to talk about.” Portraits tend to be deeply personal as well; discussing an individual artist’s perspective rather than an abstract topic like immigration policy forces debaters to consider the humanity underlying opposing arguments.

Beyond the Face: New Perspectives on Portraiture

Examining a wide range of topics, from early caricature and political vandalism of portraits to contemporary selfies and performance art, these studies challenge our traditional assumptions about portraiture.

Lemay has no illusions of bringing about a kumbaya moment between proponents of antithetical worldviews—her aim is simply the fostering of a space in which ideas can play off of one another constructively. “I think a really healthy, productive symposium is one where people disagree with each other,” she says, “and they do it in a way that’s collegial and respectful. That’s how good ideas are brainstormed. If you’re pushing someone else to expand their mind in ways they wouldn’t have done otherwise, it’s a win-win situation.”

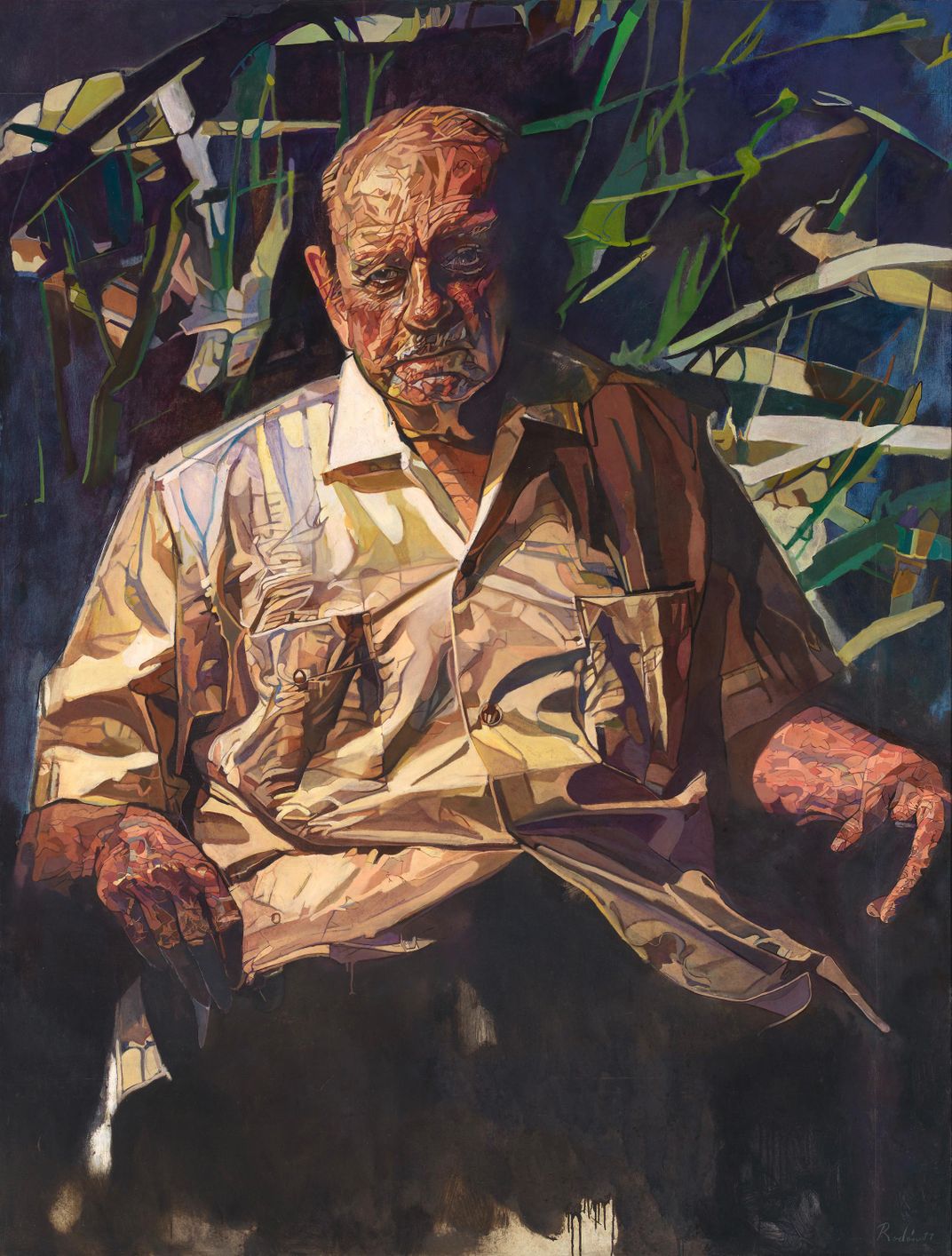

“We’re in a new era where we need to reflect,” she says. By looking beyond formalist, upper-class oil paint portraiture and incorporating examples of performance art, satirical cartoons, remixed images and tender posthumous tributes, she is optimistic that the museum should be more diverse and relevant than ever in the years to come.

“We need to make sure that our audiences see themselves when they look at portraiture.” Representation of self and community through art is not a privilege reserved to the one percent, she says. “Is art an elitist practice? It’s not. Anyone can make a portrait, and anyone should feel welcome to participate in this kind of conversation about its meaning.”

“The Edgar P. Richardson Symposium: New Perspectives on Portraiture,” organized by Kate Clarke Lemay, historian and director of PORTAL, the Portrait Gallery’s Scholarly Center and Wendy Wick Reaves, curator emerita of prints and drawings, is a two-day event to be held at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery in the Nan Tucker McEvoy Auditorium on September 20 and 21, 2018.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSC_02399_copy.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSC_02399_copy.jpg)