How Artists, Mad Scientists and Speculative Fiction Writers Made Spaceflight Possible

A new book chronicles spaceflight’s centuries-long journey from dream to reality

The realization of human spaceflight has long stood as a testament to the power of human temerity, a triumph of will and intellect alike. Pioneers such as Yuri Gagarin, Neil Armstrong and Sally Ride have been immortalized in the annals of history. Their impact on terrestrial society is as indelible as the footprints left by the Apollo astronauts on the windless surface of the Moon.

Perhaps yet more wondrous than the Cold War-era achievement of extraterrestrial travel, however, is the long and meandering trail that we as a species blazed to arrive at that result. Such is the argument of author-illustrator Ron Miller, an inveterate spaceship junkie and one-time planetarium art director at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C.

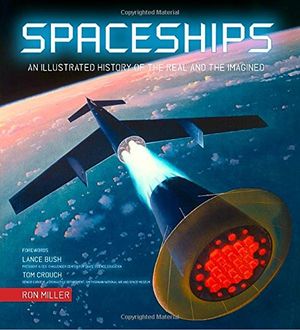

Miller’s just-published book, Spaceships: An Illustrated History of the Real and the Imagined from Smithsonian Books, is a paean to the exploratory yearning of humankind across the centuries. The profusely illustrated volume tracks technological watersheds with diligence, but its principal focus is those starry-eyed visionaries, the dreamers.

“I think astronautics is probably one of the only sciences that has its roots in the arts,” Miller told me in a recent interview. Konstantin Tsiolkovsky and Robert Goddard, key figures in the development of the physics of rocketry, he says, “would have become shoe salesmen if it hadn’t been for Jules Verne.”

Indeed, Verne, the 19th-century author fondly remembered for such classics as Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea and Around the World in Eighty Days, is a prominent player in the narrative of Spaceships—and with good reason. The Frenchman had an uncanny knack for engaging the adventurous side of his readers’ minds and with his seminal 1865 opus titled From the Earth to the Moon, kindled the imaginations of countless would-be spacefarers.

Evoking a theoretical scenario once put forth by Sir Isaac Newton, Verne envisioned a ballistic spacecraft shot from a cannon on Earth at a velocity sufficient to break free of gravity and surge onward toward the Moon. Onboard rockets, he suggested, would facilitate precision guidance. That rockets could even function in a vacuum was a shocking assertion at the time, but one whose validity would ultimately serve as the basis for modern spaceflight.

Jules Verne, though, is but the tip of the iceberg.

As Miller describes in Spaceships, everyday citizens had longed to embark from Earth on missions of discovery ever since Galileo’s early 17th-century telescopic observations, which indicated that the planets streaking through the heavens might not be the migratory stars many believed them to be, but rather worlds unto themselves—not so very different, after all, from our own lonely orb.

Most spellbinding of all, perhaps, were the Italian’s sketches of Earth’s Moon, which he published alongside other provocative findings in a tract titled Sidereus Nuncius—The Starry Messenger.

Galileo’s simple illustrations revealed the Moon for what it was: scarred, pockmarked and decidedly nonuniform. Like the Earth, this satellite was flawed—human. Gone was the ideal of a pristine white disc arcing across the night sky. For the first time, myriads began to grasp that a wholly alien landscape lay just in their backyard, silently beckoning.

From then on, thanks in large part to the work of writers and visual artists, the marvel of space and its secrets was a source of undying fascination for humans the world over, and escaping Earth was the mother of all pipe dreams. The field of astronautics had, as it were, taken off.

“Astronautics has a really long history,” Miller says. “A lot of things contributed to the first spaceship, including stratosphere balloons and submarines.” Radical technologies like these were forged in a blaze of creativity, a blaze stoked with the speculative writings of science fiction authors and their ilk.

“It’s a combination of art and science,” Miller explains. “A symbiotic relationship.”

In telling the stories of those who “kept the flame alive” from the time of Galileo through to the present day, Miller wanted to include as large and as disparate a cast of characters as he could, highlighting heroes and heroines all too often overlooked by history—folks who, as he puts it, “barely make it into the footnotes.”

One such figure was Max Valier, an intrepid experimenter who fascinated early 20th-century crowds with spectacular displays of rocketry, and who tragically lost his life in a fiery explosion at the age of 35. Valier deserves recognition, says Miller. “He lectured widely, he published popular books, and partly for that reason, spaceflight got a lot of the support it got from the people that needed to support it.”

In Miller’s view, one would be remiss to leave out such a staunch champion of spaceflight on the grounds that he didn’t invent a game-changing technology or come up with an invaluable equation. Doing so, Miller tells me, would be “unfair”—unfair in the extreme.

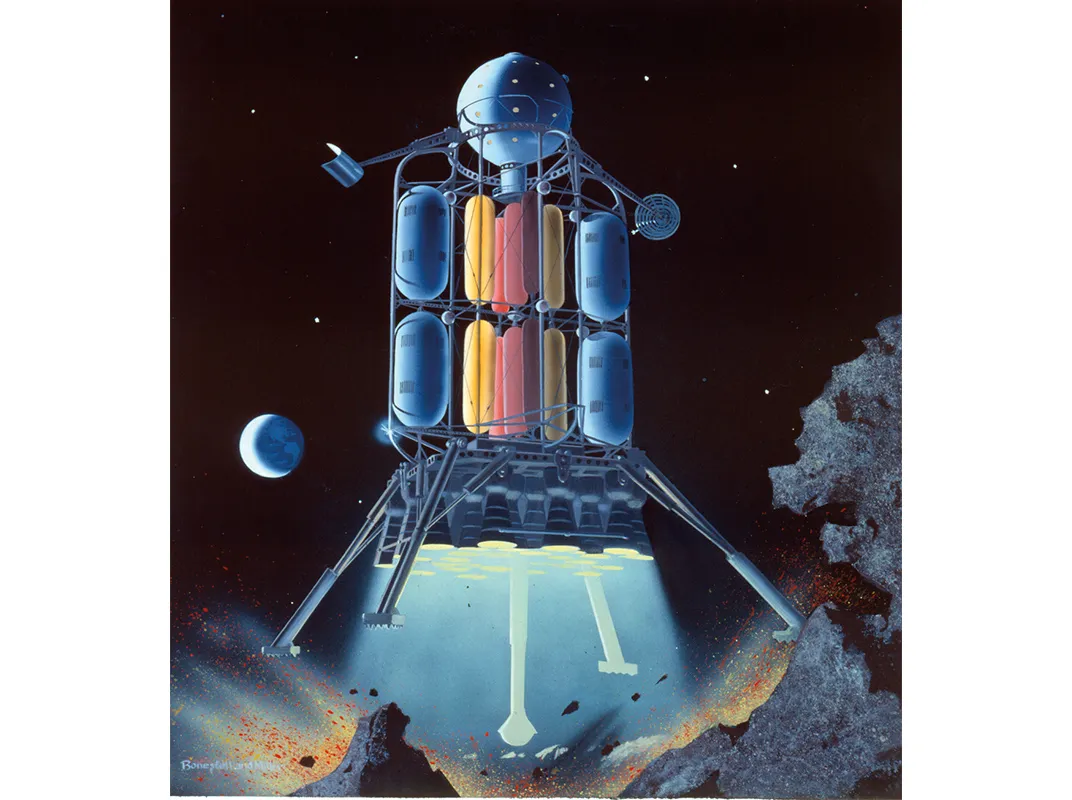

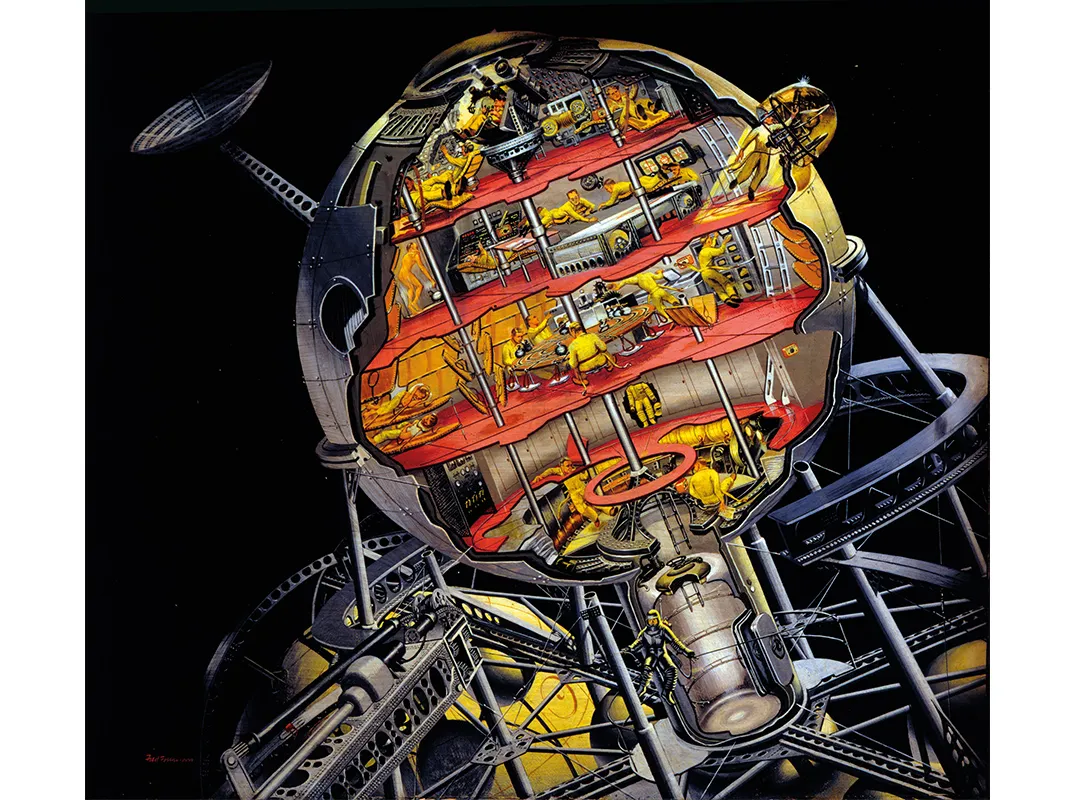

Through the efforts of Valier and other quixotic space enthusiasts—from painter Chesley Bonestell to the calculating “rocket girls” of Southern California’s Jet Propulsion Lab—the dream of spaceflight survived two World Wars and untold global turmoil. By the 1950s and 60s, in fact, it was flourishing as it had never before.

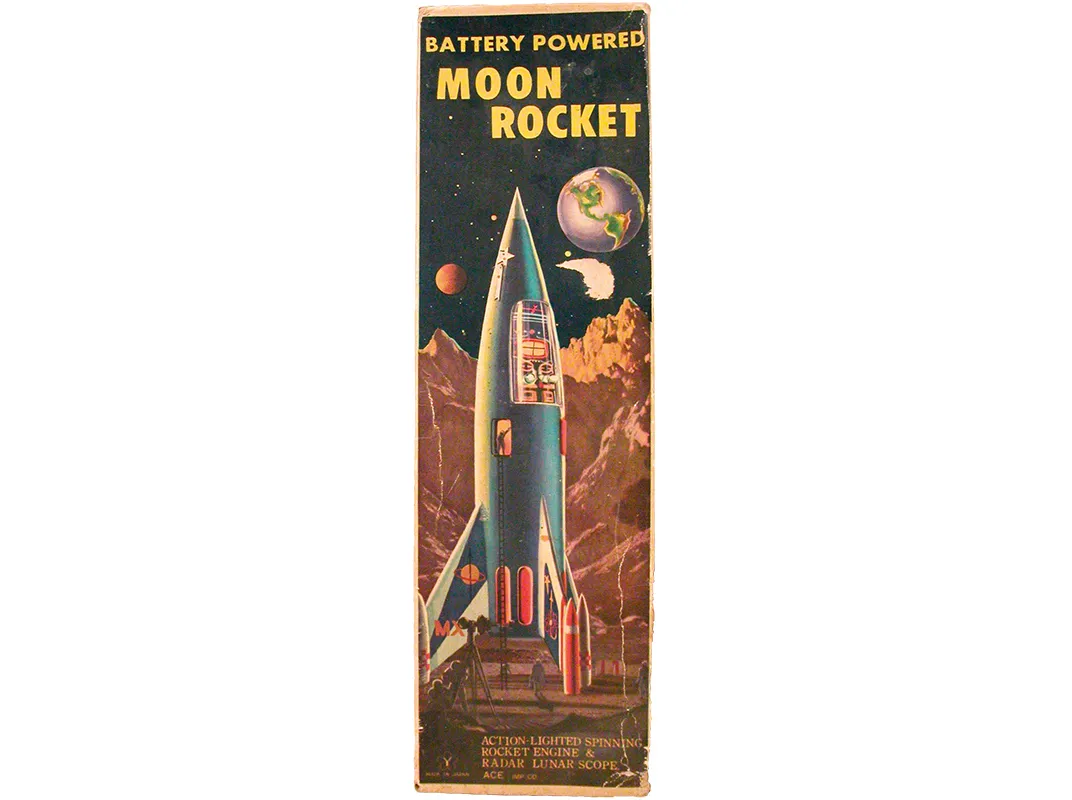

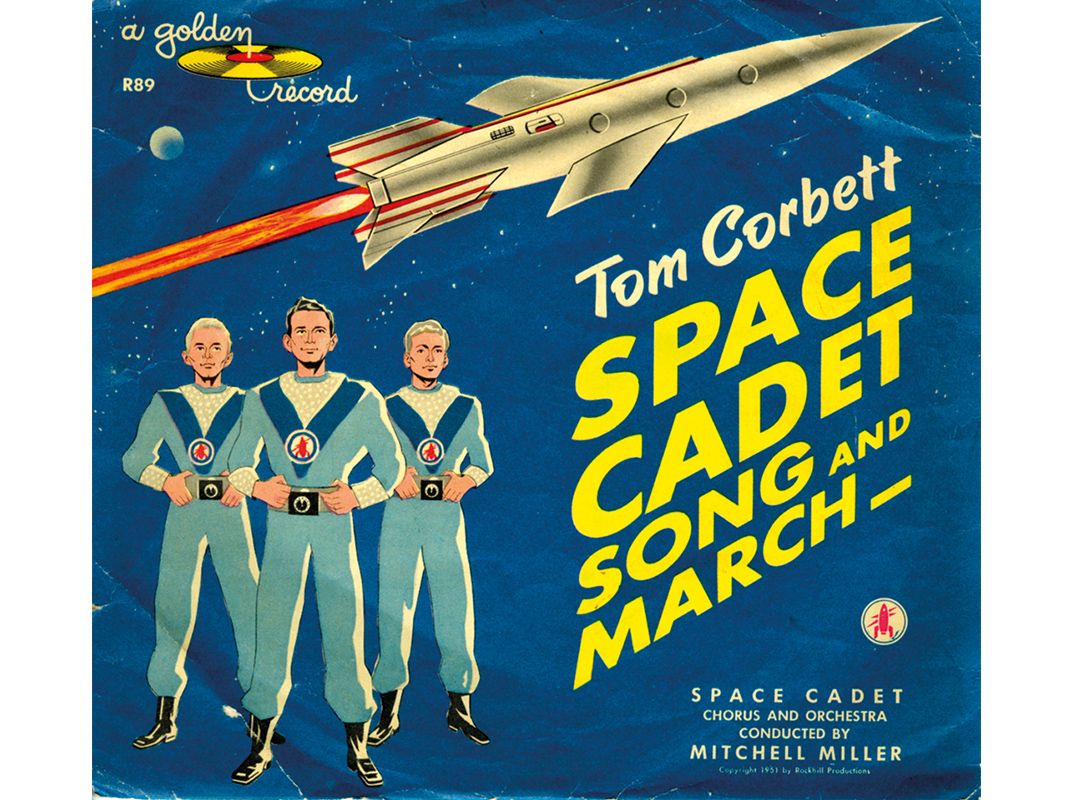

In America in those decades, Miller warmly recalls, “everything was shaped like a spaceship, or had a spaceship on it.” His book offers abundant examples of society’s all-consuming obsession with space, from pulp comics and board games to model kits and radio shows.

Stanley Kubrick’s masterpiece 2001: A Space Odyssey was perhaps the pop cultural crown jewel of the era. Never before had a filmmaker been able to bring space travel to life with such fidelity or beauty.

“There had been nothing like it ever,” Miller stresses. “It was really overwhelming.” A sci-fi-loving college student at the time of the movie’s theatrical release, Miller saw it 28 times—dazzled, like so many others, with the dream of leaving planet Earth in the rearview.

By April 1968, when 2001 made its debut, that dream was tantalizingly close to fruition.

Leveraging the elegant design of German scientist Wernher von Braun’s V-2 missile—a technology originally conceived as a means of bringing the Allied powers to their knees—the U.S. and Russia had entered the Cold War, well-equipped for a Space Race whose ultimate winner would prove to be humankind.

Now, in the wake of the orbital flights of the Mercury astronauts—and their Russian cosmonaut equivalents—America was poised to take JFK up on his audacious exhortation and send a fearless crew of spacefarers on a trip to the Moon, in what may rightly be viewed as the culmination of centuries of human wanderlust.

For all the glory and grace of the Apollo XI mission, and for all the enticing possibilities it ushered in for future adventurers, it is imperative to bear in mind that astronautics, as Miller says, “had a running start.” The giant leap made by the legends of the 1960s was but an exclamation point on the thousands of small steps it took generations of dreamers to get there.

“The science fiction and literature and art and science all came together,” Miller tells me. “In a unique way. I can’t think of any other science that’s done this.”

Spaceships, then, is no mere catalog of outmoded technologies and pop cultural baubles. Rather, it is an awe-inspiring glimpse at a select few of the near-infinite ideas it took to propel the dream of spaceflight into reality.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSC_02399_copy.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSC_02399_copy.jpg)