How a 19th-Century Photographer Made the First ‘GIF’ of a Galloping Horse

Eadweard Muybridge photographed a horse in different stages of its gallop, a new Smithsonian podcast documents the groundbreaking feat

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b7/1e/b71e206b-df4a-4d9e-958a-1a249c544c6e/the_horse_in_motion_2_resized.jpg)

In June of 1878, before the rise of Hollywood and even the earliest silent movies, Eadweard Muybridge shocked a crowd of reporters by capturing motion. He showed the world what could be guessed but never seen—every stage of a horse’s gallop when it sped across a track.

In the 19th century, it seemed as though Muybridge had used photography to stop time. When the Industrial Revolution was underway, and scholars were obsessed with identifying, cataloging and potentially mechanizing nature, Muybridge’s photo sequence of a moving horse was a milestone.

“The breakthrough is that the camera can see things that the human eye can't see, and that we can use photography to access our world beyond what we know it to be,” says Shannon Perich, the Smithsonian’s curator of photography at the National Museum of American History. A new episode of Smithsonian’s Sidedoor podcast details Muybridge’s landmark photographic accomplishment.

For years, the public was debating the workings of a horse’s gallop. The “unsupported transit” controversy asked whether or not all four of a horse’s hooves came off the ground when it runs, and it polarized both scientists and casual observers.

“We have to remember that the horse was the source of all locomotion of importance. You went to war on horses, and any kind of large-scale movement was done on horses. To understand it was really very critical,” says Marta Braun, a professor at Ryerson University, who has studied Muybridge for almost 30 years.

One person with a big stake in the debate was not a scientist, but racehorse enthusiast Leland Stanford. The 19th-century robber baron and founder of Stanford University was as ambitious as he was wealthy, and believed that emerging technology would help settle the unsupported transit controversy.

“One of the stories that you often read is that Stanford placed a bet with the owner of a San Francisco newspaper for $25,000. And the camera was going to prove whether or not the horse had all four legs suspended in the air,” Braun says, adding that the bet is likely an exaggeration.

What is true, though, is that to make his fastest racehorses go faster, Stanford wanted to understand the most granular details about how they moved, and he believed the photographer, Eadweard Muybridge, would help him do it.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e9/23/e9238434-d9f1-48a1-a0c5-d10f4200ab95/3a33596r.jpg)

At just 20 years old, Eadweard Muybridge came to the United States from England with a family bookselling business. He settled in San Francisco shortly after the Gold Rush began, and was believed to have been successful sourcing books from London and selling them in the U.S.

It wouldn’t be long, though, before his life would be filled with ingenuity, obsessive ambition and absolute melodrama. “He was an artist, he was a salesman, he was an adventurer. He wasn't afraid of the world,” says Perich.

In the 1860s, Muybridge decided to travel from San Francisco to London where he still had family. But in the first leg of his trip—a stagecoach ride from San Francisco to St. Louis—he was involved in an accident. “In Texas, the horses bolted, the driver lost control and Muybridge was thrown out of the back of the stage and hit his head,” says Braun. “He was knocked unconscious and found himself awake a day later in Arkansas and told he would never recover.”

Muybridge did make it back to London, but the people who knew him would later say that his head injury changed him forever. When he returned to the U.S. after five years, he was neither himself, nor was he a bookseller.

Helios, The Photographer

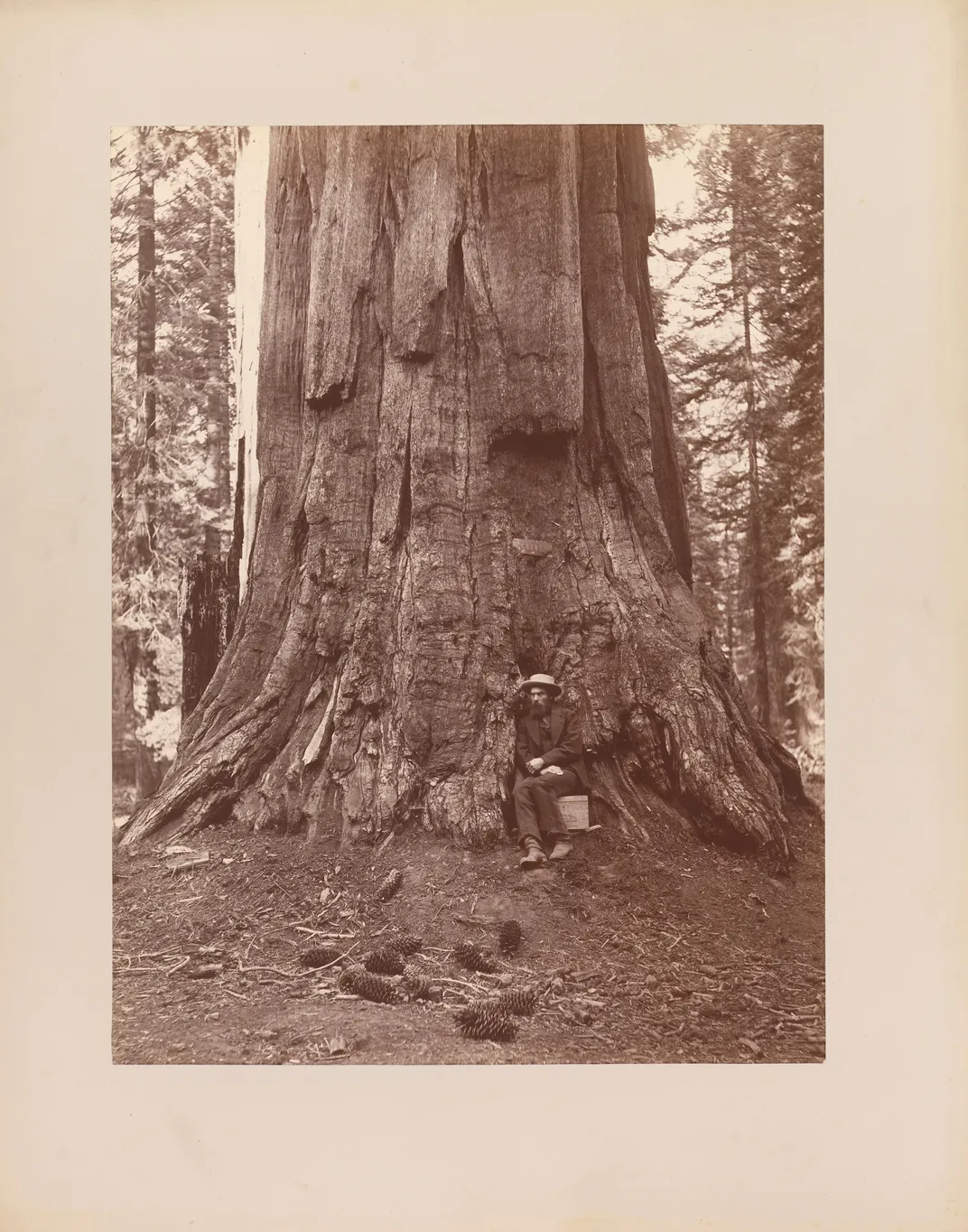

In the 1870s, Leland Stanford began working with an English photographer to get a split-second photograph of a horse that was airborne while galloping. Known for his photography of Yosemite National Park, the photographer had also been commissioned by the U.S. government to take pictures of native people in the northwest.

He had released work under the name Helios, the Greek sun god, but his real name was Eadweard Muybridge, and Stanford tasked him with capturing an image of a moving horse at a time when exposure times were so long, that the slightest movement could turn a portrait into a blurry mess.

Braun says that’s because the average exposure time in 1872 was about two seconds. “In two seconds, the horse is going to be right across the field from one end to the other. You're not going to get anything,” she says.

So Muybridge created mechanical shutters, made of wood, rubber springs and a trigger that would snap closed within one-thousandth of a second. It would be a major move away from the way most photographers controlled light exposure at the time—by manually removing a lens cap and quickly placing it back onto a camera.

The photo that Muybridge took of Stanford’s prize horse using the mechanical shutters was a disappointment, however—the image was blurry, and while a few newspapers may have printed it, the quality was too poor to settle the unsupported transit controversy or Stanford’s fabled bet.

A Breakthrough, But First, A Murder

Muybridge was said to have been obsessive about his work, something that some have wondered could have been a product of his head injury years before. Scholars today have argued that Muybridge may have injured his orbitofrontal cortex—a part of the brain associated with emotion and decision-making. Even outside of photography, Muybridge was described as erratic and emotionally volatile.

When Muybridge was 42, he married a 21-year-old woman named Flora, with whom he had a son named Florado Helios Muybridge. But Muybridge's family life was strained. “The early years of his marriage, he was making photographs in Yosemite. He would be home for a little while, and then go away for weeks at a time,” says Braun.

Muybridge found out his wife was having an affair because of a picture. One day, he came across a letter written by his wife that was addressed to Harry Larkyns, a “roguish” drama critic about town. Enclosed in the letter was a photo of Florado Helios Muybridge, and on the back of it were the words “Little Harry.”

Muybridge got a gun and boarded a train that would take him to where Larkyns was.

“He finds a cabin in which Larkyns was playing cards,” says Braun. “He knocks on the door. He asks for Larkyns. And when Larkyns comes to the door, Muybridge says, ‘I have a message from my wife,’ and shoots him dead.”

At a three-day trial for a murder that he committed in front of several witnesses, Muybridge pleaded insanity. His lawyer, who many believe was hired by Stanford, had people who had known Muybridge testify that his personality had changed drastically after the stagecoach accident.

To a skeptic, Muybridge’s personality change can sound like a narrative that could have been crafted by his lawyer, but Braun thinks the accident did have an impact on him. “I think he did change. There are pictures of him in Yosemite where he's sitting on the outcroppings of a cliff, thousands of feet high, and to me it suggests a mind that's not completely balanced,” she says, adding that Muybridge's appearance went from neatly groomed to unkempt, and was often compared to that of the bearded poet Walt Whitman.

Muybridge was eventually acquitted, but it wasn’t because of the insanity argument. The jury, which was made up mostly of married men, considered the murder of the man who had an affair with Muybridge’s wife, justifiable homicide.

In June of 1878, just a few years after he was acquitted for murder, Eadweard Muybridge made history at a racetrack in Palo Alto, California. Stanford had invited reporters to the track to witness a new age in photography and to see Muybridge capture photos of his prize horse galloping.

To do it, Muybridge hung a white sheet, painted walls at the track white, and spread white marble dust and lime on the ground, so the dark-colored horse would pop against the backdrop.

Stanford’s horse galloped down the track pulling a cart. In its path were twelve trip-wires, each connected to a different camera. As the horse sped down the path, the cart’s wheels rolled over each wire, and the shutters fired one after another, and captured the horse in different stages of motion.

After earlier photos of a horse in motion were accused of being fake or dismissed, Muybridge exposed the negatives on site, and showed the press a series of images of a galloping horse—including one of the horse with all four hooves off the ground.

Muybridge was now the man behind photography that used sequences of pictures to show motion, and he also wanted to be the man who would make those pictures move. He invented the zoopraxiscope, a device that created the primitive gif-like image of a running horse that many people associate with Muybridge.

It would project sequential images that were traced from a photograph onto a glass disc. When the disc spun rapidly and consistently, it created a looping moving picture of a galloping horse. In many ways, the invention was a frustrating one—after producing groundbreaking photography, Muybridge’s work could only be enjoyed as motion pictures if they were reproduced as drawings on a glass disc.

The zoopraxiscope was from the same lineage as projectors and optical toys, but would be exceeded by motion picture technology from inventors like Thomas Edison within a few years.

“Once you have broken a threshold, then there's a whole lot of people that will come and pick up that new idea, that revelation, that revolution, and run it out to different opportunities,” says Perich.

While Muybridge’s work photographing motion would garner the fascination of horse enthusiasts and scientists eager to understand animal locomotion, it also laid the groundwork for modern narrative-driven motion pictures, or cinema, as we know it today.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Headshot_HaleemaShah.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Headshot_HaleemaShah.jpg)