After more than a century of luring tourists with their glorious blooms, the National Park Service is actively discouraging visits to see the famous cherry blossoms along Washington D.C.’s Tidal Basin, where access will be limited or closed off completely because of the coronavirus pandemic.

There will be no parades or festivals, officials say. Access to cars and pedestrian walkways will be limited, and the Tidal Basin could be closed altogether if crowds still grow beyond safe numbers. There will be views available online with a streaming BloomCam. An “Art in Bloom” activity involves 26 oversized cherry blossom statues painted by local artists around town and three can be found at the Smithsonian’s Haupt Garden, located behind the Castle Building along Independence Avenue. Some other “pandemic-appropriate” events are also scheduled.

“The health and safety of our Festival staff and the attendees, sponsors and other stakeholders remain the Festival’s top priority,” says Diana Mayhew, president of the National Cherry Blossom Festival.

As an alternative to hanami, the time-honored Japanese tradition of flower viewing, it would be natural to suggest the blossoms found in the array of art at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Asian Art. But the Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, like the other Smithsonian museums, also continue to be closed out of a public-health caution associated with the coronavirus pandemic.

“We usually do some kind of special series of events inspired by the Cherry Blossom Festival every year, because it is such an important part of D.C.’s identity, but also as a way to bring Asia closer to the local audience, particularly Japan,” says Frank Feltens, an assistant curator of Japanese art at the museum. “This year because we cannot enter the museum and also, we are discouraged from congregating on the Mall and on the Tidal Basin to see the blossoms, we created these various online offerings.”

“We do have quite a number of works that depict cherry blossoms one way or another,” he says—some 200 out of the estimated 14,000 works from Japan alone. “Cherry blossoms are just such an important part of Japan’s visual culture to begin with.” Indeed, visitors to Japan get a stamp on their passport with a stylized depiction of a cherry blossom bough.

Feltens and Kit Brooks, assistant curator of Japanese art, chose these nine prime examples of cherry blossoms in Japanese artworks held in the museum's collections.

Washington Monument (Potomac Riverbank)

The woodblock print by Kawase Hasui (1883-1957), a prominent and prolific artist of the shin-hanga (new prints) movement, depicts some of the more than 3,000 Japanese cherry trees planted in West Potomac Park in 1912 by First Lady Helen Herron Taft and Viscountess Chinda, wife of the Japanese ambassador to the U.S. “That print was actually made in 1935 to commemorate the first Cherry Blossom Festival in D.C.,” Brooks says. “It was commissioned by a Japanese art dealer living in San Francisco.” It was by a very popular artist; Hasui was named a Living National Treasure in 1956, the year before he died.

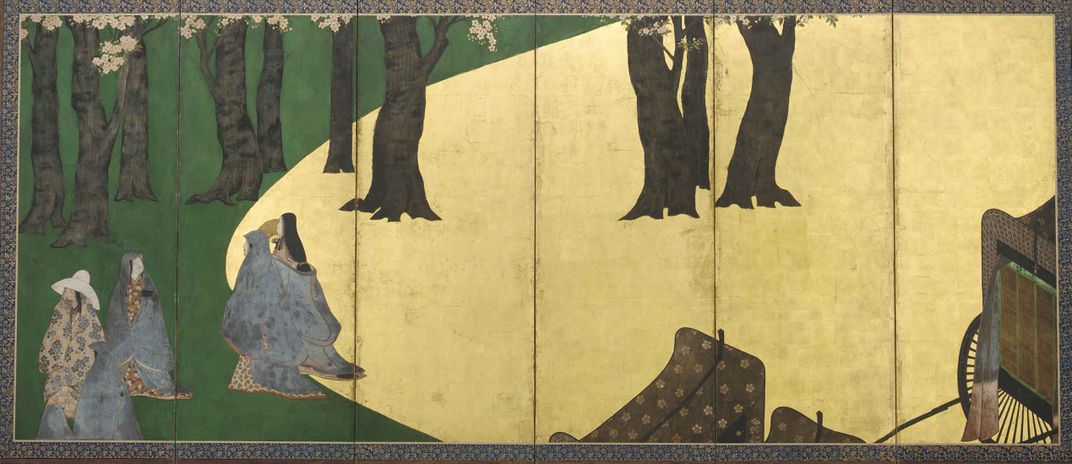

Court Ladies among cherry trees; Cherry blossoms, a high fence and retainers

The pair of six-panel screens from the Edo period depicts two scenes that have been connected to a classic work of Japanese literature from the early 11th century, The Tale of Genji written by noblewoman and lady in waiting Murasaki Shikibu. But, Feltens says, the work instead reflects a decisive move away from literary specificity. “In that sense, it’s revolutionary in its own way, using these big expanses of color, both the green and the gold are so incredibly prominent, to create these abstracted vistas, which is part of the appeal of Sōtatsu’s style.” At 5-foot-5-inches tall and nearly 25-feet across, the two screens would have immersed a viewer, Feltens says. “If you imagine that an average person in 17th-century Japan would probably be shorter than this screen, it would have been this towering vista of cherry blossoms.”

Wind-screen and cherry tree

The painted six-panel screen, nearly 12-feet wide each, shows the white flowers of a cherry blossom among the equally delightful patterns of assorted wind screens, which seem to be actually flapping in the wind. “These brightly decorated panels are hung with this red cord between the trees, as a temporary barrier,” Brooks says. “So if you were setting up a picnic, you could surround your group with these very decorative gold panels which would give you shelter from the wind as well as a little variety, while creating this really lively, beautiful backdrop, that can move with the wind, so it can move with the elements. You’re not being totally separated from the environment that you’ve chosen to spend your afternoon in.”

Incense box

A 3-D work of art celebrating spring with scenes on each surface comes from the artist Kageyama Dōgyoku. The two-tiered lacquer incense container, slightly less than 5-inches-square, is rendered in gold and silver powder and leaf with a few pieces of inlaid iridescent shell. “This is a pretty late work from the 18th century, but there has been a tradition in Japan of creating these gilded lacquer pieces for centuries before that,” Feltens says. “This is in line with that tradition of adorning these utilitarian objects with the sumptuous decors.” And while incense wouldn’t be burned in the lavish container—its basis is wood—it would smell sweetly from the incense that would be stored in it, he says.

A Picnic

Hishikawa Moronobu (1618-1694) helped popularize the ukiyo-e woodblock prints and paintings, taking what he learned from his family’s textile work to produce works like this silk hanging scroll. Moronobu was known for his distinct lines of the many figures in his work—one has a flute; three others play the traditional stringed instrument the shamisen. Twelve gather on one blanket while another eight arrive by boat. “These types of interior furnishings created natural vistas of what cherry trees could look like in the artistic fantasy,” Feltens says. “They’re similar to what they would look like in reality or nature, but idealized, for people to live with them and imagine them at times when the cherry blossoms weren’t in bloom, so you could basically live with them whenever you wanted.”

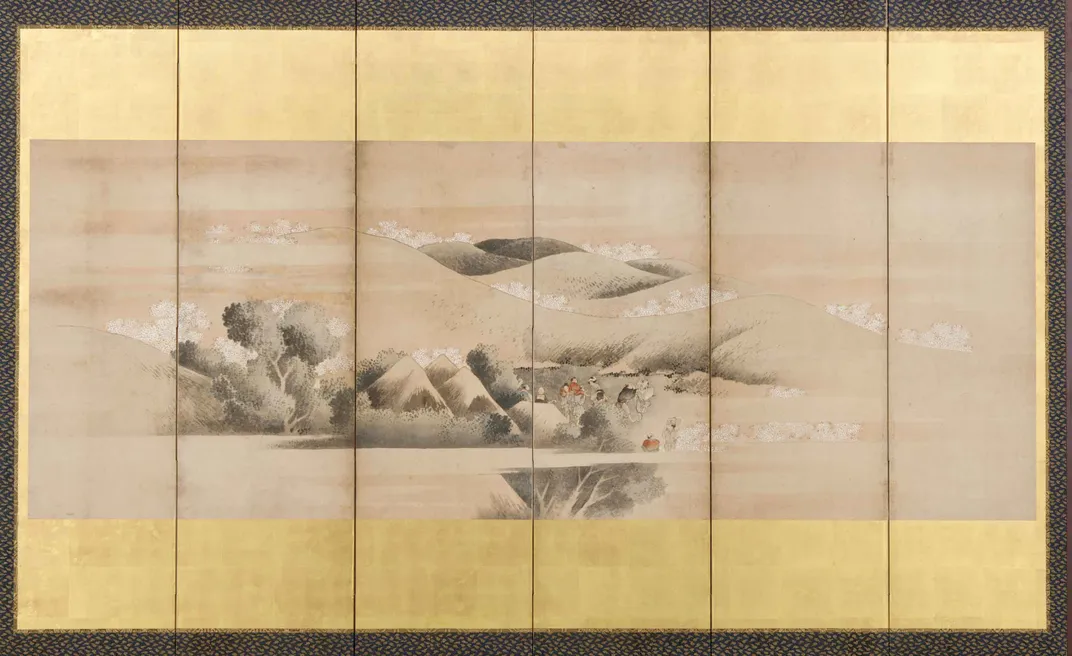

Spring Landscape

This hanging scroll from the Edo period, nearly 7-feet-tall, not only has the rare signature of its artist, Kano Tan’yū (1602-1674), but also his age, 71, and his Buddhist honorific title conferred on him a decade earlier. The rolling hills and blossoms depicted are thought to be the scenery of the mountains of Yoshino, a district near Nara famous for its spring blossoms. “There is a long centuries-old tradition in Japan to immerse yourself into these interior settings that depict landscapes of any kind, and also to compose poetry in response to them,” Feltens says. “That’s not necessarily the case with the Edo period screens we’re looking at now. But they come from a similar tradition.”

A Picnic Party

There’s no lounging in this springtime picnic, where all of its 11 figures seem to be expressively dancing to an unseen music source. Fans and parasols are among the accessories they wave as they dance, but also sprigs of sakura, or cherry blossoms, from the trees around them. The undulating shapes echo the contours of the boughs surrounding their celebrations in this hanging paper scroll of the Edo period. And it would likely enliven any indoor gathering. “Depending on the social occasion, you’re trying to create an environment for your guests, that you’re having in the room, whatever artwork you’re displaying,” Brooks says. “You’re putting it out there in order to create the environment that you want.”

Autumn at Asakusa; Viewing cherry blossoms at Ueno Park

Another work from Moronobu—25-feet-wide altogether—shows scenes from two different seasons in Edo, the city now known as Tokyo. It’s clearly autumn on the right-hand screen, where Kannonji Temple, the Sumida River and the Mukojima pleasure houses are on display. On the left, though, crowds come to see cherry blossoms in the Ueno area, where the Kaneiji Temple and Shinobazu Pond are depicted. Since the fashions shown can be traced to the end of the 17th century, it’s clear that they’ve survived their own national crisis, a March 1657 fire followed by a snowstorm that combined to kill more than 100,000 people.

Owners of such seasonal screens didn’t necessarily pull them out to reflect the time of year. “There is a certain seasonal specificity, but people back in the day weren’t necessarily adhering to that very strictly,” Feltens says.

Viewing Cherry Blossoms

This painting is attributed to the best known Japanese artist Katsushika Hokusai, ukiyo-e painter and printmaker of the Edo period. Hokusai became known for his woodblock print series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji and his iconic The Great Wave off Kanagawa. The artist is also the subject of a current exhibition at the Freer, “Hokusai: Mad About Painting,” which is also only available currently online.

“The right (second slide, above) part of it depicts this grand picnic of these ladies and gentlemen listening to music and drinking sake in a refined way,” Feltens says, “And then they all look toward the left and in the left screen you’ll see in the distance this raucous gathering that is the other form of cherry blossom season, where everybody is already very much inebriated and is so happy that they break out in spontaneous dancing. I love this screen because it shows these very different styles of enjoying the blossoms in spring.”

Also, he promises, “It will be the first thing that visitors see when the museum reopens.” To protect the works on paper, the Hokusai exhibition was always meant to have two rotations; this one was always planned for the second. “So this will be on view once we get back to a semblance of normalcy.”

Smithsonian’s National Museum of Asian Art is offering a number of online programs and activities, including a curator-led virtual tour of the “Hokusai: Mad About Painting” exhibition, an interactive docent tour exploring cherry blossoms in the collections and offering cherry blossom art for Zoom backgrounds. Other programs are: “Art & Me Preservation Family Workshop: Celebrating Cherry Blossoms” March 27 at 10 a.m.; “Look & Listen: Nature in Japanese Art and Music, Kurahashi Yodo II, shakuhachi,” with curator Frank Feltens, April 8 at 7 p.m.; “Teacher Virtual Workshop: Slow Looking and Hokusai,” April 10, 11 a.m.; “Jasper Quartet: Music for the Cherry Blossom Festival,” April 10, 7:30 p.m.; and “Meditation and Mindfulness” with a focus on objects from the museum's Japanese collections, April 2 and April 9, noon.

To view the blossoms on the Tidal Basin, check out the BloomCam and the Art in Bloom program offers numerous activities and ideas for celebrating the Cherry Blossoms at other locations around the city, or in your own communities.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/22/79/2279ddaf-c50f-4695-9d33-ebc9eca79e38/longform_mobile2.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/75/dc/75dc7669-6083-4c9e-99c8-9473cd1c9103/longform_desktop2.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)