Historic Bell Helps Ring in New African American History Museum

Why President Obama won’t cut a ribbon when the new museum opens this Saturday

When word leaked out that President Lincoln had issued the Emancipation Proclamation, the 1863 document outlining the legal end of slavery in the United States, jubilation swept through the North. As far north as Vermont, church bells rang out in celebration. And on Friday, as America’s first African-American president dedicates America’s first national museum of African-American history, a famous bell will be rung in an echo of that happy day 153 years ago.

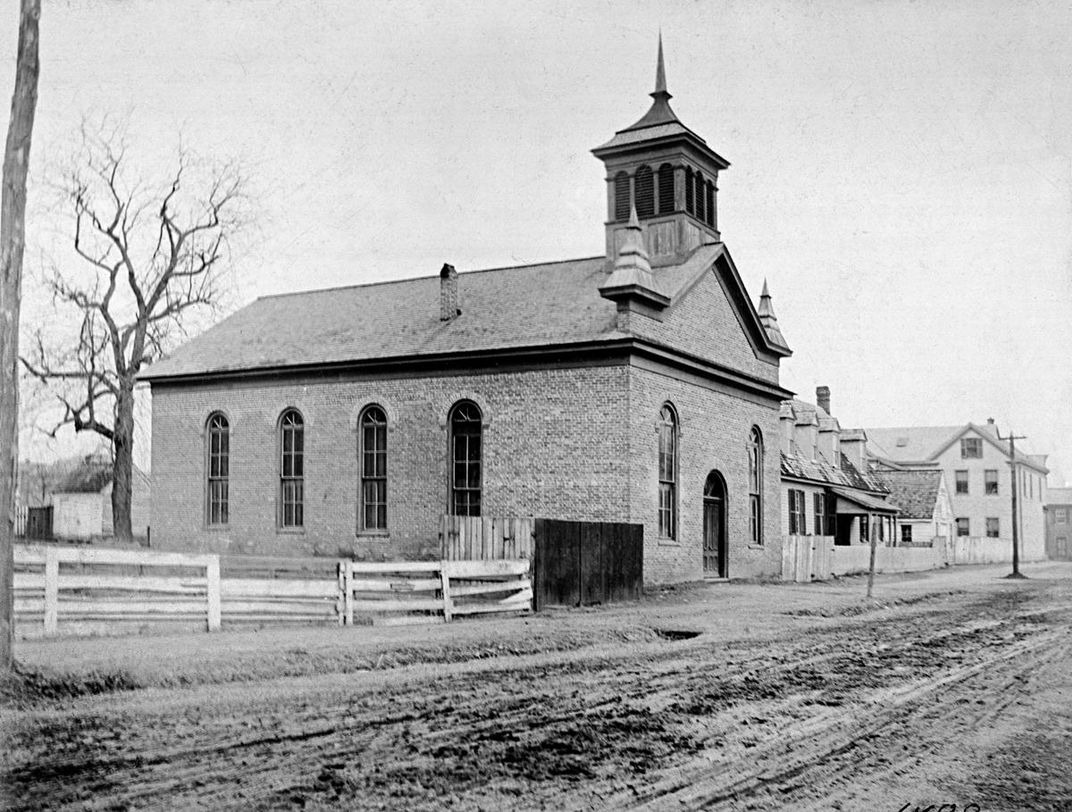

The bell in question is called the Freedom Bell, and it was specially restored for the event. Cast in 1886 to celebrate the 100th anniversary of Williamsburg, Virginia’s historic First Baptist Church, the bell has long stood silent. That will all change on Friday, though, as the newly restored bell makes a trip to Washington for the the opening of the National Museum of African American History and Culture. As the President rings the Freedom Bell in lieu of a ribbon-cutting, bells all over the country will ring in unison. At last count, at least 17 churches around the nation had plans to ring their bells in celebration.

“Everything’s coming full circle,” says Pastor Reverend Dr. Reginald Davis, who presides over the congregation of First Baptist. Davis wasn’t in church—he was riding on a bus that accompanied the bell from Williamsburg to Washington. And for the pastor, who is known for his scholarship on African-American icons like Frederick Douglass and his work interpreting scripture through an African-American lens, the bell means more than a chance to ring in a new museum.

“This bell represents the spirit of America,” Davis explains. For over a century, it’s been connected with a church whose history reads like a litany of the struggles and challenges faced by African-Americans throughout the nation’s history. Founded in 1776, the church was founded in defiance of laws that prevented black people from congregating or preaching. Gowan Pamphlet, the church’s first pastor, organized secret church outdoor church services for slaves and free people and survived whippings and accusations of criminal activity for the sake of his freedom to worship. But the church survived, and in memory of the congregation’s struggle for liberty and the wider struggles of African-Americans, the church’s women’s auxiliary raised money for a commemorative bell.

The Freedom Bell immediately took on an important role for the first Baptist church organized entirely by African-Americans. But history was not kind to the bell—it remained silent throughout much of the 20th century after falling into disrepair. That silence coincided with hard years for African-Americans, who had to contend with virulent racism and Jim Crow laws long after slavery’s technical end.

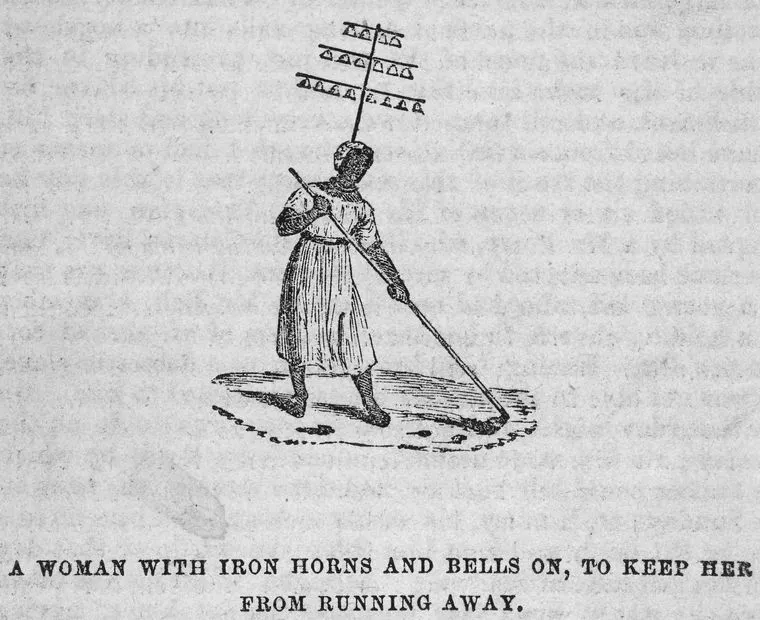

Bells have a long connection to the struggle for African-American civil rights in the United States. Perhaps the most famous example is Philadelphia’s Liberty Bell, which was adopted as a symbol of freedom by abolitionists and patriots alike during the 1830s. But they have links to oppression, too: Many slaves were forced to respond to plantation bells while working in the fields, and some were even fitted with personal bells designed to keep them from escaping.

After slavery ended, sound became inextricably linked with the struggle for African-American civil rights, from the strains of “We Shall Overcome” at Selma to Mahalia Jackson’s rendition of “Amazing Grace” at multiple Civil Rights rallies to President Obama’s intonations of the same song during his eulogy for Reverend Clementa Pickney, who was gunned down at the 2015 shooting of nine black churchgoers in Charleston. And then there was Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., whose booming “I Have a Dream” speech reminded Americans to let freedom ring.

For Davis, the sound of the newly-restored bell evokes both past and present. “We felt that this bell needs to be rung again so that we can help make our nation a more perfect union,” he said. “Looking at our current climate of racial division, of government division, we feel that we need to ring this bell again to bring us all together and to remind us that we are one nation under God.”

Restoring the 130-year-old bell was no easy task. Funded in part by the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, the work finished up in time for Black History Month, when members of Davis’ congregation challenged themselves to ring the bell continuously for the entire month of February, in part to make up for the many events it never commemorated.

But the bell’s brief foray to Washington will not be its last sounding. After the museum opens, the 500-bell will be carted back home and rehung in the church. And you can ring it once it returns: The church is inviting members of the public to sign up to ring the bell themselves this October.

Whether you ring the bell in person, take part in a virtual bell-ringing by using the hashtag #LetFreedomRingChallenge online, or just watch the President ring in the new museum, Davis hopes you’ll remember the significance of its sound. “I’m part of an ongoing storytelling about a people up against significant odds,” he explained. “Due to their faith, courage and perseverance, [African-Americans] have been able to struggle on and help make our country live up to its creed.” Though that struggle is made more challenging by factors like ongoing police brutality against young African-American men and a climate of racial tension, he said, it can be easy to wonder if the nation has regressed. “Do we want to go back?” he asked. “What kind of progress will we continue to make? I think America wants to move forward.”

Can that work be accomplished by a single bell? Probably not—but by celebrating the culture and accomplishments of African-Americans, Davis hopes the museum and the bell will ring in a new era of cooperation and hope. “We see this as unfinished work,” he said. “The work goes on.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erin.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erin.png)