The Grisly Details of Early Anatomy Textbooks

These images detail the inner workings of human bodies in all their gruesome glory

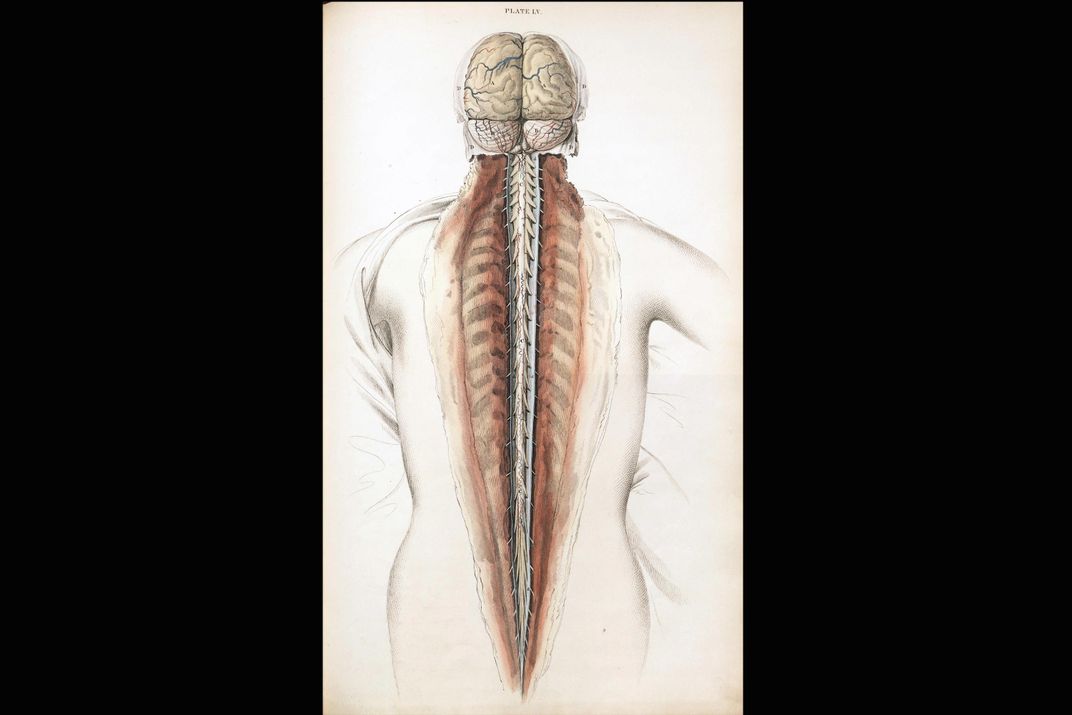

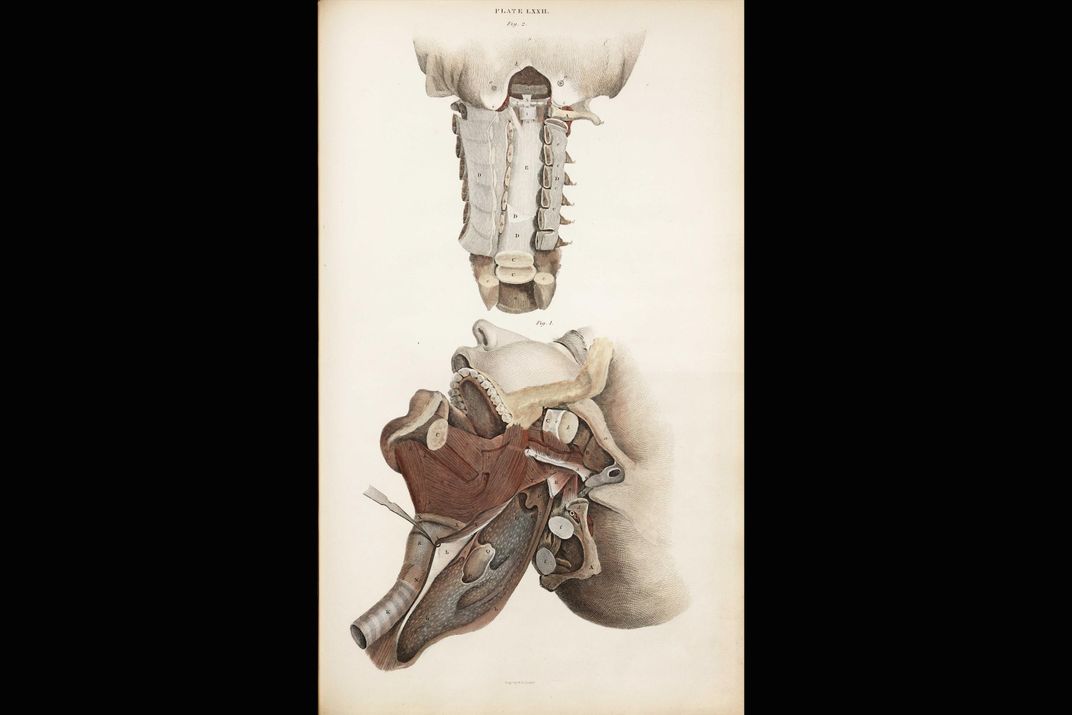

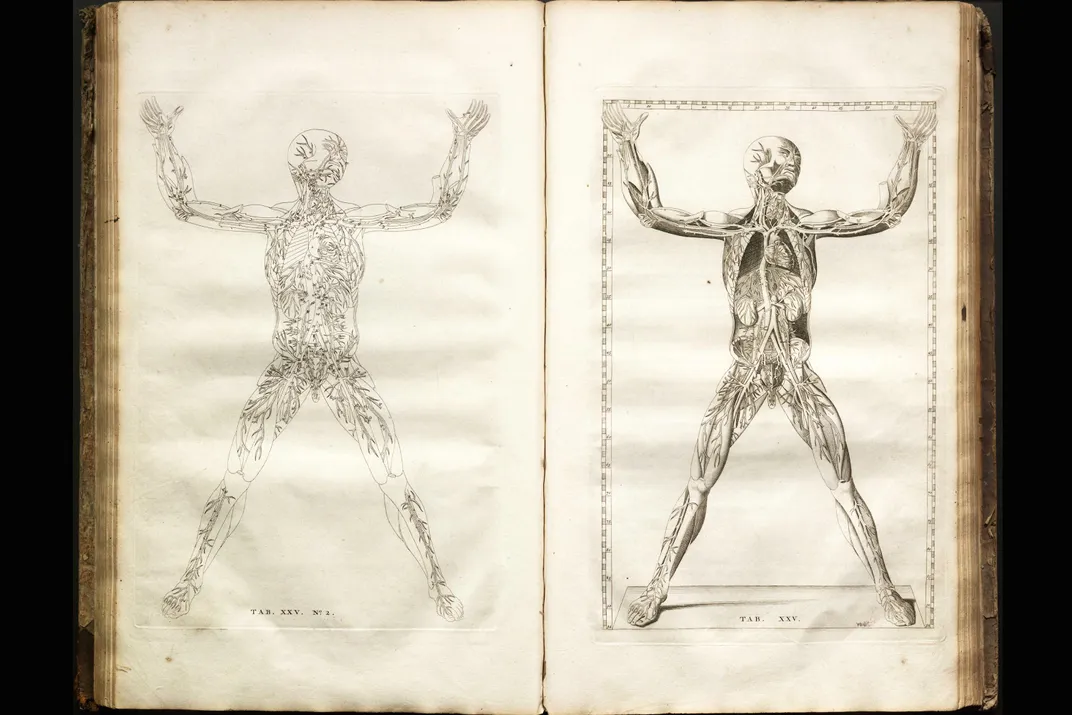

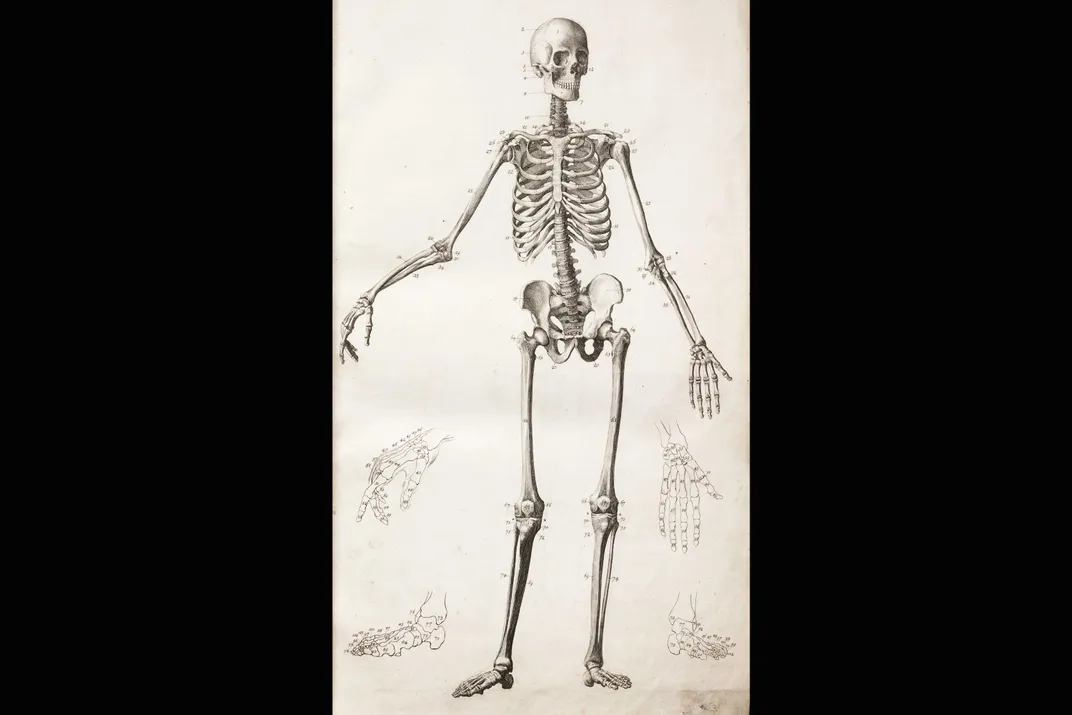

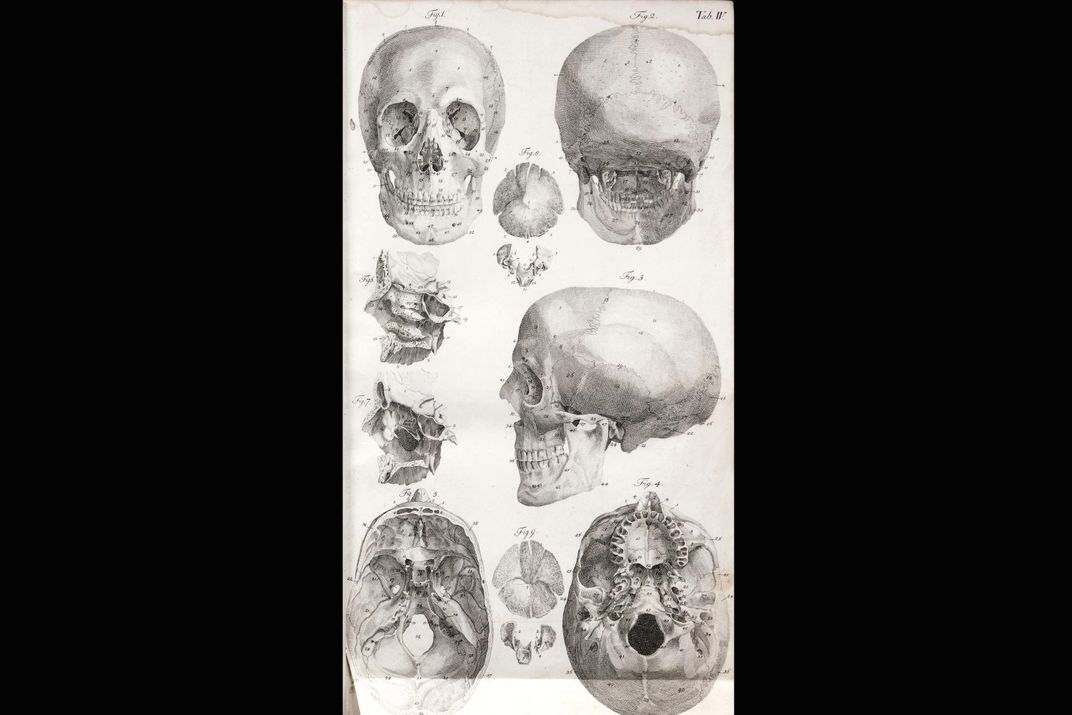

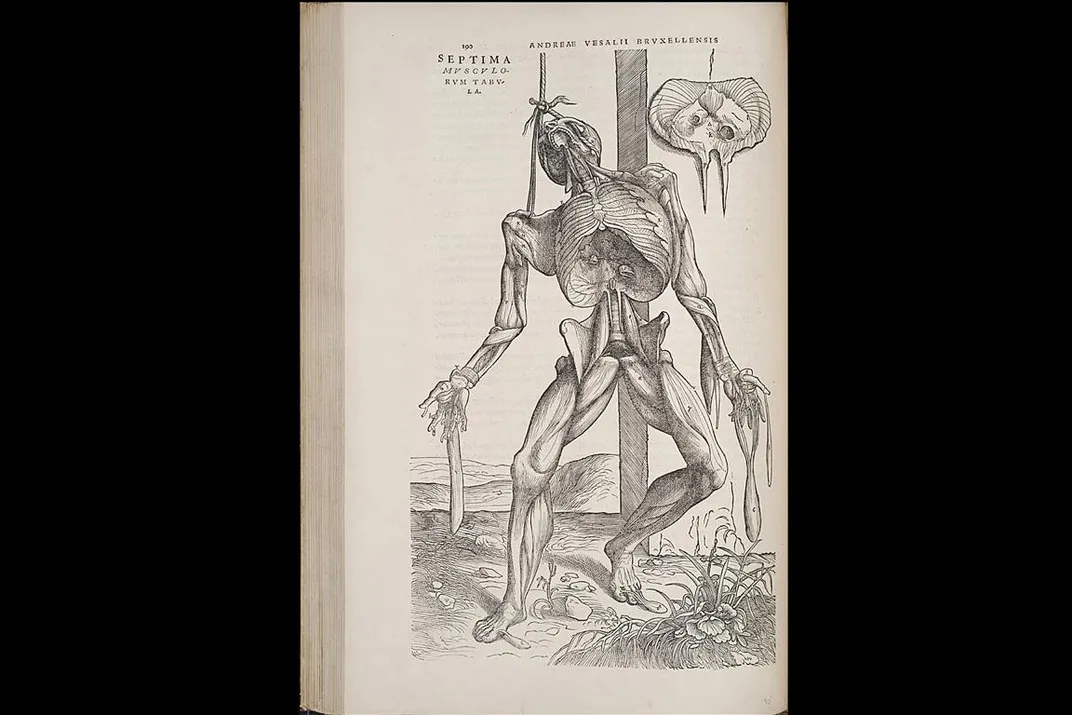

Early pioneers of the medical field went to great pains to learn about the intricate inner workings of human bodies—studying and sketching every muscle, organ and bone to compile detailed descriptions and images of humans turned inside out.

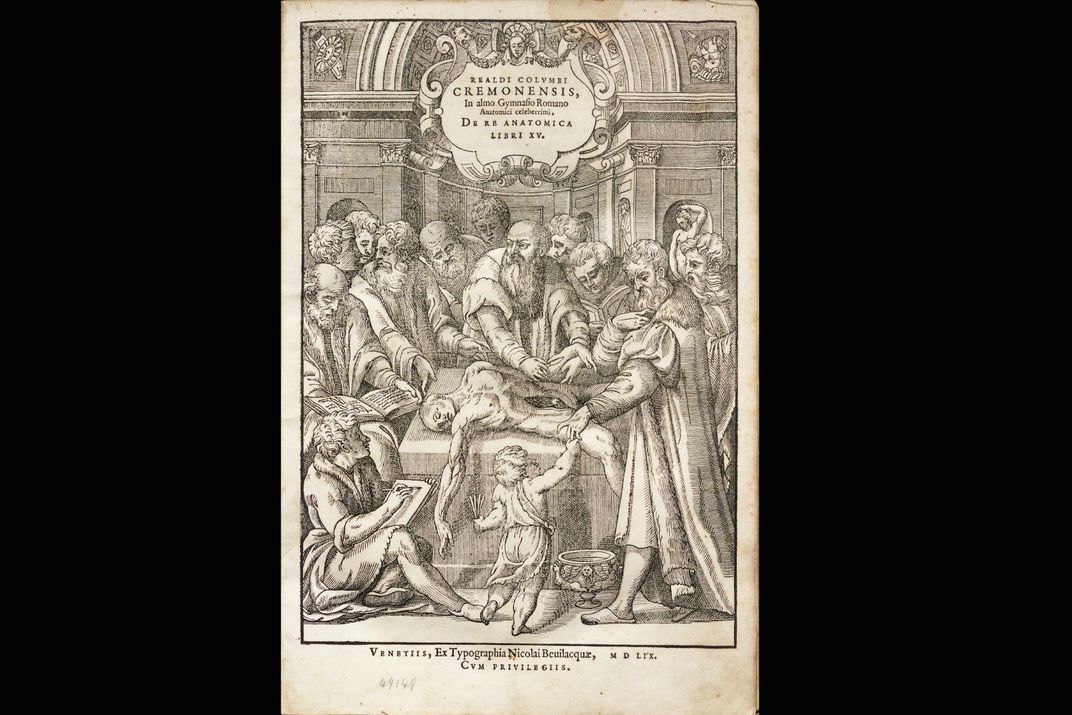

At the time these images were highly controversial, since dissection of human corpses was taboo. Before the 16th century, majority of medical texts were mostly devoid of images, making it more difficult to teach, learn, and advance the medical field.

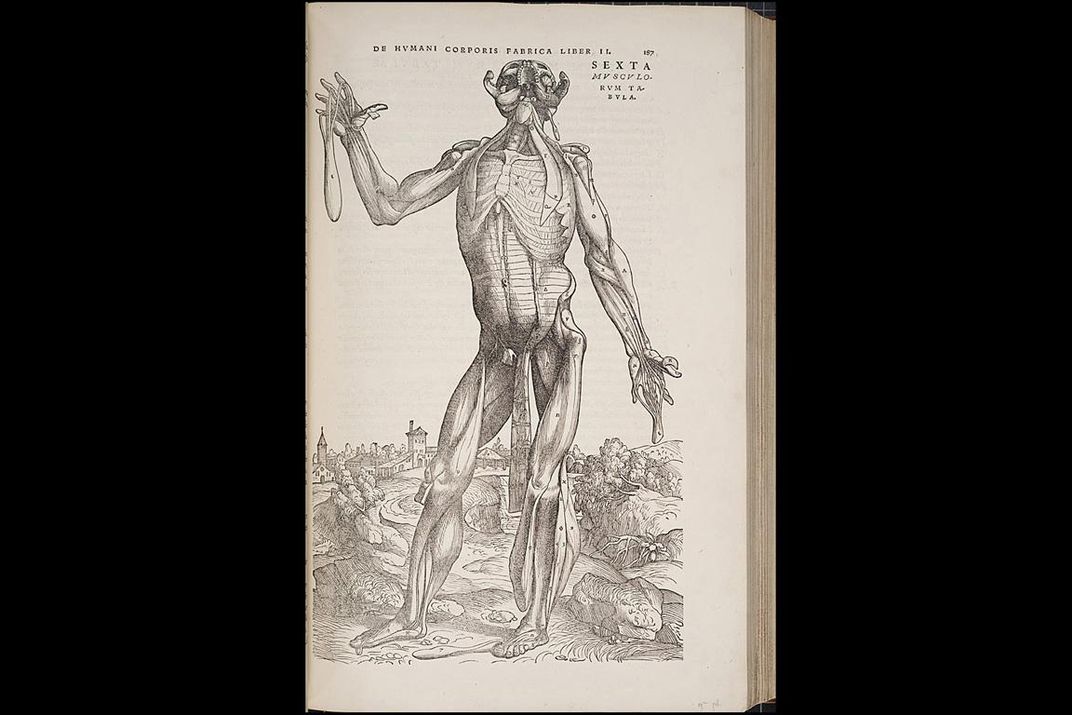

But that slowly changed when Flemish physician Andreas Vesalius came on the scene. An exemplary teacher, he tirelessly advocated the need for anatomical images and hands-on dissection practice. And in 1543, he published the famous De Humani Corporis Fabrica, the first medical text rife with images depicting human anatomy in exacting detail.

“An immense achievement, this almost 700 pages long huge folio volume [is] one of the heralds of the scientific revolution,” says Lilla Vekerdy, head of special collections at the Smithsonian Libraries.

Even then, scientists like Vesalius needed real, but deceased, subjects for study and illustration.They often dissected the bodies of hanged criminals, explains Vekerdy. All the way through the 19th century, so-called “body-snatchers”—who often dug up graves—were a major source of medical cadavers for both teaching and creating these detailed illustrations.

These carefully constructed images paved the way for later greats in the medical field to continue to study and detail the human form in all of its gruesome glory.

On October 29, at 1 p.m. ET, the Smithsonian Libraries is serving up an eerie tour of these centuries old anatomy books via the online video platform Periscope. Join in to learn more about the grisly details of these important milestones in medical history.

Editor's note (October 29, 2015): Andreas Vesalius' origins were corrected from Finnish to Flemish.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Wei-Haas_Maya_Headshot-v2.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Wei-Haas_Maya_Headshot-v2.png)