For Every Object, There Is a Story to Tell

A Smithsonian curator is asked to select just one artifact

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/eb/5e/eb5e9314-88b2-4a40-bd15-45699832f55b/702_6685abweb.jpg)

New York Times reporter Sam Roberts author of the book, A History of New York in 101 Objects, recently asked several museum experts about what had led them to become most interested in “stuff,” what we technically call “material culture.” For Neil MacGregor, head of the British Museum, it was a pot of French yogurt. Asking for it during a youthful sojourn whetted his appetite for learning another language, propelling him toward more cosmopolitan horizons. For Jeremy Hill also of the British Museum, it was something more utilitarian—a word processer. For Louise Mirrer, president of the New York Historical Society, it was the egg-shaped IBM pavilion at the 1964 World’s Fair. Then, he asked me.

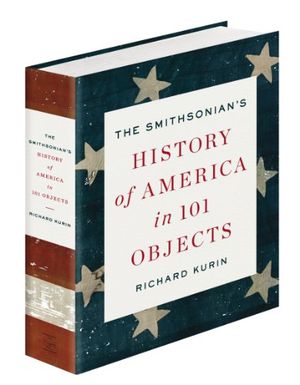

It’s one thing to choose items from the Smithsonian’s collection for their significance to our national life and history, as I did for the book, The Smithsonian’s History of America in 101 Objects. It’s quite another thing to recall the object that led to an inspirational moment. In the 1950s and early 1960s, like many, I collected baseball cards, comic books and coins. The rarity of a Mickey Mantle card or a Superman in the first Action Comics, or a 1909-S-VDB penny held powerful sway for me as a young boy—but didn’t change my life.

As an adventurous teenager living in New York City where there were no buffalo or alligators, and milk came packaged or dispensed from a machine, I remember being transported to another place and time by the totem poles and the great Haida cedar canoe in the lobby of the American Museum of Natural History. I spent hours gazing into the museum’s renowned dioramas, enchanted by taxidermy animals staged against the backdrop of those magnificent painted murals.

A turning point though came when as an 18-year-old undergraduate my buddy got the idea that we take a semester of independent study and travel to India. We needed money to do that and one of our professors suggested that maybe the Natural History museum would pay us to collect things for them. He told us to call one of his mentors at the museum—she was Margaret Mead. We were naïve amateurs—but with guidance from the museum’s South Asian anthropology specialists Stanley Freed and Walter Fairservis we got the gig. We started learning Hindi and figuring out how to conduct an ethnographic study of a village—a type of research then in scholarly vogue, so we could get academic credit.

The museum gave us a few thousand dollars to collect artifacts illustrating peasant life. In India, my pal went off to find a guru, and I ended up living in a Punjabi village. I tried to learn another language and practice my fledgling ethnography skills. Most villagers resided in mud huts and farmed wheat, rice, cotton and sugar cane. For a city boy, learning about growing crops and dealing with livestock was as fascinating as delving into local customs and understanding India’s religious traditions and beliefs. Over the course of several months, I amassed a small mountain of artifacts. Fairservis was interested in looms and I found one. I paid village craftsmen and women to make woven mats, wooden beds and pots. Some objects, like swords, clothing, turbans and colorful posters of gods and goddesses I purchased in a nearby town. I traded for objects—“new pots for old,” the village watchman would bellow, making his daily rounds and informing residents about this crazy American’s puzzling quest. Much of what I collected was mundane; items of everyday agricultural and household routine—jars, churns, baskets and bridles.

One day I came across a village elder hunched over an ancient spinning wheel in her simple one room mud-built home. The wheel was made of wood and roughly, but beautifully, hewn. Its construction combined heft and lightness in all the right places—there was an inherent dignity which the maker had imparted to it, and the woman honored that with an air of respect for the tool as she worked, spinning cotton grown in the fields just yards from her home. The quiet intensity of her spinning native cotton with that wheel was spectacular. I was once again, like those days at the museum, transported. I still have a fading snap shot (above) of the wheel and the woman, and a strong memory frozen in my mind.

It was no wonder that Gandhi had used the cotton spinning wheel, or charkha, as a symbol of long-lived self-reliance for India’s independence movement. I couldn’t imagine acquiring this wheel—it was too connected to this woman’s life. But months later her son came to my door. His mother was ill; she’d never spin again, and the family could use the money. I was saddened and guilt-ridden and overpaid them quite a bit. I would have preferred that woman continued to spin forever.

I gave the spinning wheel a number in my inventory—6685 A&B 107—and a description, something for the record utterly devoid of its emotional significance. It went into a storehouse I used in the village. Later, it was transported to Delhi—I had collected two truckloads of artifacts—and by ship to the U.S., and finally to the museum’s collections facilities. I don’t know if the spinning wheel was ever put on exhibit at the museum.

Meanwhile, because I had learned so much about what I didn’t know during my time in that village, I decided to head off to the University of Chicago to study for a PhD in cultural anthropology.

So 44 years later when Roberts asked me to name an object, I told him about the old woman’s spinning wheel. And when I searched the American Museum of Natural History’s website, I couldn’t believe my eyes when I found it. But joy turned to sadness.

The sanitized image of the spinning wheel and the clinically precise metadata used to describe it stripped away all of the significance and backstory of its history and the last woman who had used it.

When I’d first come to work at the Smithsonian in 1976, it was for the Folklife Festival held annually in the summer on the National Mall. This living exposition of culture had been championed by S. Dillon Ripley, one of the formative secretaries here at the Smithsonian, who in response to what he saw as the stuffy, dusty, artifact-crowded museums of the day, ordered curators to “Take the instruments out of their cases and let them sing.” He and the Festival’s founding director Ralph Rinzler wanted to show how people used, made and were connected to the treasures in the collections. And that’s what I told Roberts, it was the spinning wheel, but more than the object, it was also the old woman, and her hut and her fields of cotton and her family and her children and her grandchildren. It was the entire experience. I’ve now spent the better part of four decades working on making those connections between people and artifacts, and telling the backstories, and providing the context to material culture— that which makes “stuff” so interesting.

The Smithsonian's History of America in 101 Objects

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/kurin.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/kurin.png)