Tricksters walk a fine line in our folk imagination. So long as their tricks remain playful, even if somewhat mischievous, we enjoy their company and the opportunity to laugh, especially if their cleverness challenges figures of authority. However, if their tricks become cruel or sadistic, or demean those who are relatively powerless, we may reject them entirely.

The new Disney+ television series, Loki, which premieres this week, must walk this fine line with its title character, dubbed the “god of mischief.” Produced by Marvel Studios, the six-part series takes Loki (played by Tom Hiddleston) through complicated adventures, traversing the realm of dark elves, alternate timelines and threats of catastrophic devastation that should be familiar to dedicated fans of the Marvel Cinematic Universe.

For folklorists, however, Loki’s place in the pantheon of trickster heroes is even more universal.

“Loki has attracted more scholarly attention during the past century than perhaps any other figure in Norse mythology, primarily as a result of his ubiquity and importance in the surviving mythological documents and the almost universally acknowledged ambiguity of his character,” writes scholar Jerold Frakes.

Some sources characterize Loki as the son of two giants, who abandoned him in battle with Odin, one of the leading gods in Norse mythology. Other sources indicate that Odin and Loki became blood brothers and undertook adventures with Thor, who also figures prominently in the Marvel Cinematic Universe.

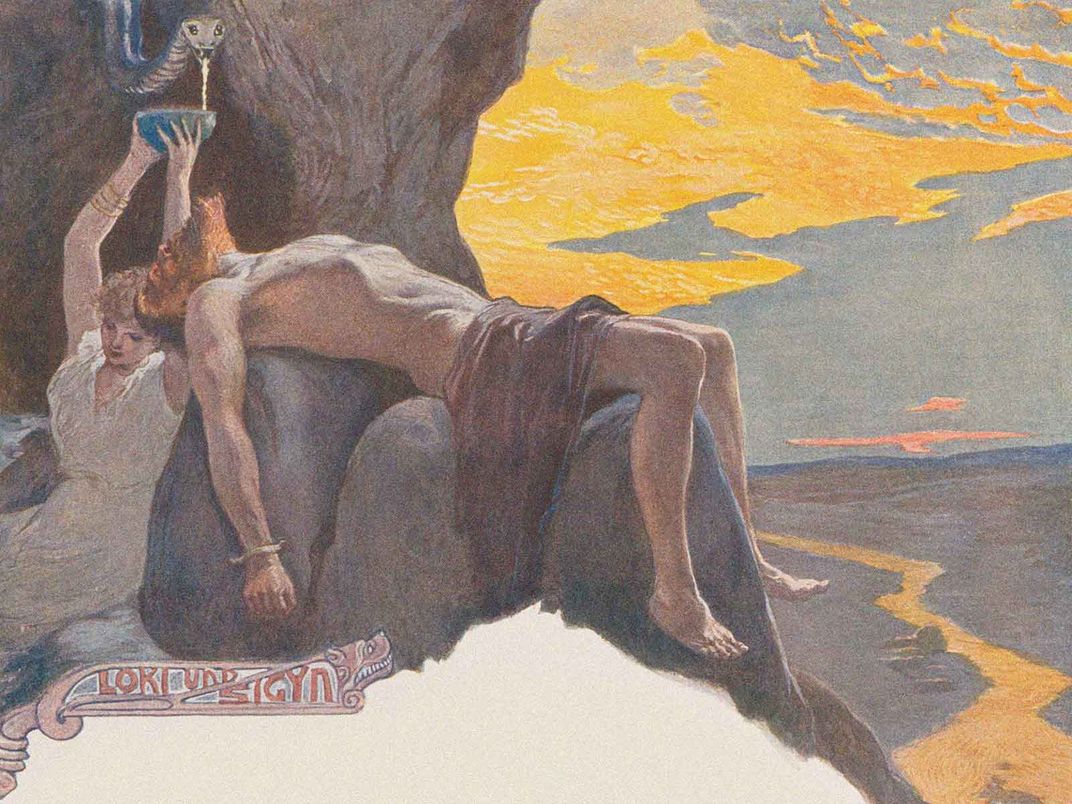

Jacob Grimm, best known for the fairy tales he and his brother Wilhelm collected, was one of the first to propose Loki as a god of fire, and to draw similarities between Loki and the fire demon Logi in Norse mythology. Other scholars see Loki as a shortened name for the devil Lucifer, or perhaps derived from loca (Old English for prison). The latter may relate to an especially gruesome myth in which Loki—imprisoned in a cave and held fast by the solidified entrails of his son Narvi—cannot escape until the apocalyptic end, known in Norse mythology as Ragnarok. This particular myth spares no grisly detail. Narvi’s entrails are available because cruel gods transformed his brother Vali into a wolf, who then devoured Narvi. A poisonous serpent slowly releases its venom to drip onto Loki’s face, which causes him to shriek in pain and the Earth to quake.

This part of Loki lore probably will not appear in any episodes of the new television series. Based on some of the advance previews and speculation, we know that this particular manifestation of Loki will be arrogant, stubborn, unpredictable, super-smart and insubordinate to authority. In one of the trailers, Agent Mobius (played by Owen Wilson) from the mysterious Time Variance Authority tells Loki they are going someplace to talk. “Well, I don't like to talk,” Loki declares—to which Mobius replies, “But you do like to lie. Which you just did, because we both know you love to talk.”

All of these characteristics—from arrogance and insubordination to intelligence and chattiness—are primary features of the trickster hero, a folkloric character found worldwide and also highly appropriate for a god of mischief. Parallels to Loki abound, from tricksters like Narada in Hindu mythology or Susanoo in Shinto mythology to multiple figures among many Native American tribes.

“The central characteristic of the Trickster is that he (usually, although sometimes she) has no fixed nature,” writes the poet and artist Tim Callahan. “Just when we’ve decided he’s a villain, he does something heroic. Just when we’re sure he’s a fool, he does something intelligent. . . . Yes, the Trickster does charm us, even when we know he’s lying.”

In many instances, the trickster takes the form of an animal like Big Turtle from the story-telling tradition of the Pawnee on the Central Plains. One of the best examples of the trickster’s guile and ability to talk his way out of any situation is recorded in Stith Thompson’s 1929 Tales of the North American Indians. Hearing that hostile humans will place him on hot coals, Big Turtle warns them: “All right. That will suit me for I will spread out my legs and burn some of you.” Next, hearing that they’ve decided instead to immerse him in boiling water, Big Turtle declares: “Good! Put me in, and I will scald some of you.” And finally, hearing that they will throw him into a deep stream, Big Turtle cries: “No, do not do that! I am afraid! Do not throw me in the water!” And, of course, as soon as the people throw Big Turtle into the water, he swims to the surface and taunts their gullibility. Such is the way of the trickster.

Coyote tricksters prevail in Native American tales of the Southwest. A raven trickster triumphs in Native American stories in the Northwest. A shape-shifting trickster who frequently appears as a spider is the mischief maker in West African and Caribbean folklore. In one well-known African American tradition, the crafty character Brer Rabbit outwits larger animals, such as the fox, using reverse psychology to reach the safety of the briar patch. Of course, another trickster rabbit is Bugs Bunny, which brings us back to other television and big screen pranksters from Woody Woodpecker to Bart Simpson to Jack Sparrow to The Joker in the Batman series to Fred and George Weasley in the Harry Potter franchise.

Trickster figures—whether human or animal, whether traditional or cinematic—share several key elements of folk wisdom. Tricksters are smaller than their rivals. Loki is no match physically for his half-brother Thor, much less for other Marvel superheroes. But the success of the trickster demonstrates that you don’t need extraordinary physical prowess to win the day. Mere mortals may take much satisfaction in this turning of the tables.

Tricksters illustrate the capriciousness of nature, or perhaps even embrace chaos theory, which asserts that chaos and order are not necessarily in opposition. “Our timeline is in chaos,” Mobius tells Loki. And who better to restore order than the god of mischief himself? This bit of folk wisdom may reassure those who too often find the world incomprehensible.

Tricksters may transform the world for good. In Northwest Coast mythology, the raven brings fire and light to the world. Humankind receives agriculture from the Shinto trickster Susanoo and journalistic news from the Hindu trickster Narada. Rumor has it that Loki in the new television series may be able to alter human history, which may help counter the alternate folk belief that the world as we know it is nearing its end.

We do not expect this new version of Loki to conclude with everyone living “happily ever after.” But we may hope that this particular god of mischief will not only amuse, but also successfully navigate the folkloric traditions of the trickster.

Editor's Note, June 21, 2021: Norse mythology scholars say that Loki's parentage is contested. An earlier version of this article inaccurately described Loki's parents as Odin and Frigga. This article clarifies the scholarship and is updated with new sources.

:focal(291x94:292x95)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/2c/79/2c79ebe0-5eb8-4738-aa1c-acf83e049a0b/mobile_lokie.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/11/37/11375dee-fe85-4411-890d-68ce46e2b36d/loki.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/James_Deutsch.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/James_Deutsch.jpg)