Why is Turquoise Becoming Rarer and More Valuable Than Diamonds?

With depleting mines, turquoise, the most sacred stone to the Navajo, has become increasingly rare.

A sky-blue colored stone with a gray and gold spiderweb matrix sits melded into an intricate silver ring with engraved feathers along the sides. This one piece of jewelry may have taken years to make and is worth thousands of dollars, but the story it tells is priceless. It’s the story of a stone, of a culture, a history and of tradition—the story of the Navajos.

The stone is turquoise, an opaque mineral, chemically a hydrous phosphate of copper and aluminum. Its natural color ranges from sky blue to yellow-green and its luster from waxy to subvitreous. The mineral is typically found in arid climates—major regions include Iran (Persia), northwest China, the Sinai Peninsula in Egypt and the American Southwest. The word itself is derived from an Old French word for “Turkish” traders who first brought the Persian turquoise to Europe. It has graced the halls and tombs of Aztec kings and Egyptian pharaohs, such as Tutankhamun, whose golden funeral mask is inlaid with turquoise.

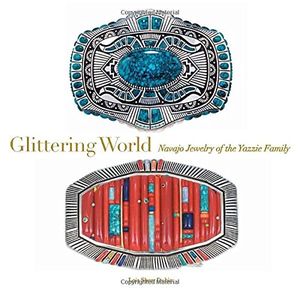

The importance of this gem lies far beyond its name (Doo tl’ izh ii in Navajo) and characteristics in the culture as showcased in the exhibition “Glittering World: Navajo Jewelry of the Yazzie Family,” which opened last week at the National Museum of the American Indian in New York City. The show features more than 300 examples of contemporary jewelry made by the Yazzie family of Gallup, New Mexico. It is the museum’s first exhibition to explore the intersection of art and commerce and the personification of culture through jewelry. Although turquoise is not the only stone incorporated in the jewelry, it may be the most important.

“Turquoise is a great example of a secular and sacred stone,” says Lois Sherr Dubin, the curator for the “Glittering World” exhibition. “There is no more important defining gem stone in Southwest jewelry and part of the exhibition’s purpose is to expose people to turquoise that is not dyed or stabilized, but is the authentic stone.”

Turquoise is a central element in Navajo religious observances. One belief is that to bring rainfall, a piece of turquoise must be cast into a river, accompanied by a prayer. Its unique hue of green, blue, black and white represents happiness, luck and health and if given as a gift to someone, it is seen as an expression of kinship.

There are some 20 mines throughout the American Southwest that supply gem-quality turquoise, the majority of them are in Nevada, but others are in Arizona, Colorado and New Mexico. According to turquoise expert Joe Tanner, when Spanish conquistador Coronodo took home riches to the Spanish king, the turquoise from the jewelry was traced back to the Cerrillos mine in New Mexico, the oldest known in America.

“What the Yazzies work with is the finest from the mines,” says Dubin. “We’re saying it’s more rare than diamonds.”

Less than five percent of turquoise mined worldwide has the characteristics to be cut and set into jewelry. Once a thriving industry, many Southwest mines have run dry and are now closed. Government restrictions and the high costs of mining have also impeded the ability to find gem-quality turquoise. Very few mines operate commercially and most of today’s turquoise is recovered as a byproduct of copper mining.

Despite the lack of mines in North America, turquoise is readily available on the market, with more than 75 percent coming out of China. However, much of this turquoise has either been filled with epoxy for stabilization or enhanced for color and luster.

Lee Yazzie, known as one of the world’s leading crafters of this artform, prefers his turquoise from the Lone Mountain in Nevada. “I was exposed to the stone in my early life,” he says. “My mother wore it and I remember her working with turquoise to make rings and other pieces. Later, I learned it was considered a sacred stone.”

He set out to find the sacredness of this stone. “One day, I tried to connect to that spirit. I started talking to it and said, ‘I have very little knowledge on how to work with you and need you to give me direction on what it is you want.’ I can testify to you that when I started communicating in this very special way, I discovered why the Navajos considered turquoise to be sacred—everything is sacred in this life.”

This idea of sacred and secular coincides with the idea of preserving tradition through innovation, a common theme in the Yazzie family’s production of jewelry.

“My tradition has always been in my work, no matter how contemporary my pieces look,” says Raymond Yazzie, whose jewelry is distinguished by the quality of his domed inlay work.

“The ability to take traditional forms and make it contemporary is a clear expression of how native people have transitioned from their traditional cultures into a world that is very different,” says Kevin Gover, the museum's director, “yet they have managed to retain their cultural identity.”

Raymond incorporates turquoise into his designs, although he is better known for his use of coral, which he says is also rare when trying to find good quality.

“The Lone Mountain and Lander Blue mine are coming to be like diamonds," says Raymond, "with how much you pay for the turquoise."

“Glittering World: Navajo Jewelry of the Yazzie Family” runs through January 10, 2016 in New York City at the National Museum of the American Indian's Heye Center, is located at One Bowling Green, across from Battery Park. The exhibition will be accompanied by a gallery store that features the work of up and coming Navajo artists.

On December 6 to 7, the National Museum of the American Indian in New York hosts the 2014 Native Art Market from 10 a.m. – 5 p.m. The free event in the Diker Pavillion, first floor, brings many of the best well-known and up-and-coming contemporary Native artists to New York City and includes jewelry makers, basket and traditional weavers, sculptors and ceramic artisans. A ticketed preview party and lecture "Sustainability in native Art & Design" on December 5, features the opportunity to meet the artists, sample Native American influenced food and drink, and tour the exhibition,”Glittering World: Navajo Jewelry of the Yazzie Family.”

Glittering World: Navajo Jewelry of the Yazzie Family

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ff/d5/ffd51b8d-21c1-4b3b-8755-094eb11b7d32/37_ring-copyweb.jpg)