The Definitive Story of How the National Museum of African American History and Culture Came to Be

From courting Chuck Berry in Missouri to diving for a lost slave ship off Africa, the director’s tale is a fascinating one

:focal(821x1113:822x1114)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b5/32/b532eccb-ff8b-4292-b168-e8dd1d145f82/sep2016_k04_lonniebunch.jpg)

In July 2005, I began this great adventure by driving from Chicago to Washington, D.C. to take a new job. The trip gave me plenty of time to ponder whether I’d made the right decision. After all, I loved Chicago, my home in Oak Park and my job as president of the Chicago Historical Society. But it was too late to turn back. I had agreed to become the founding director of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture—an opportunity, and an obligation to my community, that far outweighed my reservations.

On my first day on the job, I was told we’d have temporary offices somewhere off the National Mall. And when I say “we,” I mean me and the only other person on the staff, Tasha Coleman. Tasha and I searched for our offices and found them locked, so we went down to the building’s front desk and asked for a key. They said, we don’t know who you are; we’re not just going to give you a key.

I then went to the building’s security office and informed them that I was the new museum director and I wanted access to my offices. The officer said no, because we have no record of you.

I called back to the Castle, the Smithsonian headquarters building, and confirmed that we were supposed to be allowed in. As I stood looking foolishly at a locked door, a maintenance man walked by pushing a cart holding some tools. One of those tools was a crow bar. So we borrowed it and broke into our offices.

At that moment, I realized that no one was really prepared for this endeavor, not the Smithsonian, not the American public and maybe not even me.

This September 24, the museum’s staff—which now numbers nearly 200—will formally welcome the public into the National Museum of African American History and Culture, the Smithsonian Institution’s 19th museum. We’ll be opening a $540 million building on the National Mall, with 400,000 square feet to house and display some of the more than 35,000 artifacts that we’ve collected from all over the world. What a time it is to open this museum, at the end of the tenure of President Barack Obama and during a period where there is a need for clarity and understanding around issues of race.

First, though, I want to tell you a little about how we got to this point.

**********

This moment was born out of a century of fitful and frustrated efforts to commemorate African-American history in the nation’s capital. It was in 1915 that a group of African-American veterans of the Civil War proposed a museum and memorial in Washington. In 1929, President Calvin Coolidge actually signed enabling legislation for a memorial celebrating “the Negro’s contributions to the achievements of America,” but the Great Depression put an end to that.

Ideas proposed during the 1960s and ’70s found little support among members of Congress. The desire to create a museum was resurrected in the 1980s thanks to Representative Mickey Leland of Texas, among others. A bill introduced by Representative John Lewis of Georgia in the late ’80s spurred the Smithsonian to launch a formal study of what an African-American “presence” on the National Mall might be. The study concluded that that presence should be a separate museum, but budget concerns curtailed the initiative.

In 2003, a commission appointed by President George W. Bush studied the question again and issued a report whose title reflected its verdict: “The Time Has Come.” Congress passed the law authorizing the museum that year.

All that was left for the museum’s director to do was to articulate a vision, hire a staff, find a site, amass a collection where there was none, get a building designed and constructed, ensure that more than $500 million could be raised from private and public sources, ease the apprehension among African-American museums nationwide by demonstrating how all museums would benefit by the creation of NMAAHC, learn to work with one of the most powerful and influential boards of any cultural institution and answer all the arguments—rational and otherwise—that this museum was unnecessary.

I knew that the new museum had to work as a complement to the National Museum of American History on the Mall. I’d worked there for 12½ years, first as a curator and then as the associate director of curatorial affairs. (A colleague and I collected the lunch counter from the Greensboro sit-ins, one of the museum’s signature artifacts.) But I’ve been a historian for my entire professional life. I knew that the story of America is too big for one building.

The Smithsonian does something no other museum complex can: opens different portals for the public to enter the American experience, be it through the Smithsonian American Art Museum, or the National Air and Space Museum, or the National Museum of the American Indian. The portal we’re opening will allow for a more complicated—and more complete—understanding of this country.

The defining experience of African–American life has been the necessity of making a way out of no way, of mustering the nimbleness, ingenuity and perseverance to establish a place in this society. That effort, over the centuries, has shaped this nation’s history so profoundly that, in many ways, African-American history is the quintessential American history. Most of the moments where American liberty has been expanded have been tied to the African-American experience. If you’re interested in American notions of freedom, if you’re interested in the broadening of fairness, opportunity and citizenship, then regardless of who you are, this is your story, too.

Museums that specialize in a given ethnic group usually focus solely on an insider’s perspective of that group. But the story we’re going to tell is bigger than that; it embraces not only African-American history and culture, but how that history has shaped America’s identity. My goal for the last 11 years has been to create a museum that modeled the nation I was taught to expect: a nation that was diverse; that was fair; that was always struggling to make itself better—to perfect itself by living up to the ideals in our founding documents.

The vision of the museum was built on four pillars: One was to harness the power of memory to help America illuminate all the dark corners of its past. Another was to demonstrate that this was more than a people’s journey—it was a nation’s story. The third was to be a beacon that illuminated all the work of other museums in a manner that was collaborative, and not competitive. And the last—given the numbers of people worldwide who first learn about America through African-American culture—was to reflect upon the global dimensions of the African-American experience.

One of the biggest challenges we faced was wrestling with the widely differing assumptions of what the museum should be. There were those who felt that it was impossible, in a federally supported museum, to explore candidly some of the painful aspects of history, such as slavery and discrimination. Others felt strongly that the new museum had the responsibility to shape the mind-set of future generations, and should do so without discussing moments that might depict African-Americans simply as victims—in essence, create a museum that emphasized famous firsts and positive images. Conversely, some believed that this institution should be a holocaust museum that depicted “what they did to us.”

I think the museum needs to be a place that finds the right tension between moments of pain and stories of resiliency and uplift. There will be moments where visitors could cry as they ponder the pains of the past, but they will also find much of the joy and hope that have been a cornerstone of the African-American experience. Ultimately, I trust that our visitors will draw sustenance, inspiration and a commitment from the lessons of history to make America better. At this time in our country, there is a great need for contextualization and the clarity that comes from understanding one’s history. I hope that the museum can play a small part in helping our nation grapple with its tortured racial past. And maybe even help us find a bit of reconciliation.

**********

I was fascinated by history before I was old enough to spell the word. My paternal grandfather, who died the day before I turned 5, always read to me, and one day he pulled out a book with a photograph of children in it. I can’t remember whether they were black or white, but I can remember him saying, “This picture was taken in the 1880s, so all of these kids are probably dead. All the caption says is, ‘Unidentified children.’” He turned to me and asked, “Isn’t it a shame that people could live their lives and die, and all it says is, ‘Unidentified’?” I was stunned that no one knew what became of these children. I became so curious that whenever I looked at vintage images I wondered whether the people in them had lived happy lives, had they been affected by discrimination and how had their lives shaped our nation.

Understanding the past was more than an abstract obsession. History became a way for me to understand the challenges within my own life. I grew up in a town in New Jersey where there were very few black people. Race shaped my life at an early age. I remember a time from elementary school, when we were playing ball and it was really hot. We lined up on the steps in back of one kid’s house, and his mother came out and started handing out glasses of water. And when she saw me, she said, “Drink out of the hose.” As I got older, I wanted to understand why some people treated me fairly and others treated me horribly. History, for me, became a means of understanding the life I was living.

In college and graduate school I trained as an urban historian, specializing in the 19th century. And while I taught history at several universities, I fell in love with museums, especially the Smithsonian Institution. I like to say that I am the only person who left the Smithsonian twice—and returned. I began my career as a historian at the National Air and Space Museum. Then I became a curator at the California African American Museum in Los Angeles. From there I returned to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, and then I led the Chicago Historical Society. And now I am back once again.

One of my favorite books, which I often used in my university classrooms, is Jean Toomer’s Cane, an important short-story collection from the Harlem Renaissance. One of the stories involves a couple who live on the first floor of a building and a man who’s chained and hidden on the upper floor. The couple is always fighting; they just can’t seem to figure out the cause of their tension. The man on the second floor symbolizes the memory and impact of slavery. The book suggests that until this couple—until America—comes to grips with that person upstairs, they’ll never find peace.

The Smithsonian is the great convener, bringing diverse points of view into contact. A primary goal of the museum is to help America find whatever peace it can over issues of race.

**********

Getting this museum organized was like taking a cruise at the same time you’re building the ship. Hundreds of priorities, all urgent, all needing attention from my very small band of believers. I decided that we had to act like a museum from the very beginning. Rather than simply plan for a building that would be a decade away, we felt that it was crucial to curate exhibitions, publish books, craft the virtual museum online—in essence, to demonstrate the quality and creativity of our work to potential donors, collectors, members of Congress and the Smithsonian.

With no collections, a staff of just seven and no space to call our own, we launched our first exhibition, in May 2007. For “Let Your Motto Be Resistance: African-American Portraits,” we borrowed rarely seen works from the National Portrait Gallery. We enlisted a dear friend and a gifted scholar, Deborah Willis, as the guest curator. We exhibited the work at the Portrait Gallery and at the International Center of Photography in New York City. From there it went on a national tour.

That strategy became our way of making a way out of no way. Later we obtained a dedicated space within the Museum of American History, and I started hiring curators who reflected America’s diversity. At times I took some flak, but if I was arguing that we were telling the quintessential American story, then I needed a variety of perspectives. Now the diversity of my staff is a point of pride for me and should be for all who care about museums.

As the staff grew, we organized 12 exhibitions, covering art (Hale Woodruff’s murals, the Scurlock Studio’s photographs), culture (Marian Anderson, the Apollo Theater) and history, which meant confronting difficult issues head-on. We intentionally did exhibitions that raised provocative questions, to test how to present controversy and to determine how the media or Congress might respond. “Slavery at Jefferson’s Monticello: Paradox of Liberty,” a collaboration with the Monticello historic site, was kind of a watershed. Of course, the subject of slavery went to the very core of the American dilemma, the contradiction of a nation built on freedom while denying that right to the enslaved. Slavery is one of the great unmentionables in contemporary American discourse, but we felt we had to confront the subject in a way that showed how much of America’s past was shaped by what was then called the “peculiar institution.” We featured one of those iconic statues of Jefferson, but we put it in front of a wall that had the 600 names of the enslaved residents of Monticello, both to humanize them and to show that one cannot understand Jefferson and the other founding fathers without grappling with slavery.

Another challenge was raising the money to build and outfit the museum. Ultimately we needed to raise $540 million from public and private sources. I was often reminded just how large that number was, usually in insomniac moments around 2 a.m. Maybe the first week or two after I arrived here, we received our first major donation, a million-dollar gift from Aflac, the insurance company. I was so exultant, I shouted, “Yeah, baby, we can do this!” And then someone reminded me that the museum would need hundreds more checks like that to reach our goal. Great. I realized I would probably need to make more than a thousand presentations.

Traveling to make those presentations, I saw more trains, more planes, more rental cars, more hotel rooms than anybody should have to. But I learned two important things. The first is how far I can go in one day: Denver and back. Any farther, my body falls apart. The second came in 2008, when we began fund-raising in earnest right as the country faced its worst economic catastrophe since the Great Depression. Things were bad, but I was overwhelmed by the support the museum received even in the worst of times. The key to the museum’s fund-raising success was the work of the creative development staff, plus the leadership of Dick Parsons, Linda Johnson Rice and Ken Chenault. Along with the other members of the Museum Council, they gave of their time and their contacts to help make the museum a reality. America is indebted to their volunteer service.

Maybe it was the curator in me, but what worried me the most was whether we could find the stuff of history, the artifacts that would tell the story of this community. Some of the early plans for the museum de-emphasized artifacts, partly out of a belief that there were few to be collected and technology could fill any void. But I already knew that even if you have the very best technology, a tech-driven institution would fail. People come to the Smithsonian museums to revel in the authentic, to see Dorothy’s ruby slippers, or the Wright Flyer, or the Hope Diamond, or the Greensboro lunch counter. So the most pressing question on my mind was: Where were we going to find collections worthy of the rich history of the African-American?

The first object walked right in the door. Within my first month, I got a call from someone at a nonprofit in Washington who said a scholar from Latin America wanted to meet me. My wife was still back in Chicago and I was working late hours, and there was no one else left in the office. I said, sure.

This scholar, Juan Garcia, who identified himself as a black Ecuadorean, came over and started talking about the importance of this new museum. He explained that he’d heard about my vision of African-American history as the quintessential American story. He added: “If you are able to centralize this story, it will give a lot of us in other countries hope that we can do that. Because right now the black experience in Ecuador is little known and undervalued.” We ended up talking for a good long time before he said, “I want to give you a present.” So he reached into this box and pulled out a carved object of a type that was completely unfamiliar to me.

Historically, Garcia’s community had fled into the swamps in order to escape slavery, so their primary mode of transportation was the canoe. And the role of elderly women was to carve canoe seats. What he had was a canoe seat that had been made by either his mother or grandmother. On the seat she had carved representations of the Anansi spider, the spirit that looms so large in West African folklore. So I was sitting in Washington with someone from Ecuador who had just given me an artifact that had strong ties to Africa—a powerful reminder that we were telling not just a national story, but a global one as well.

From there the collection grew and evolved along with the concept for the museum. While we did not have a specific list of objects initially, as the museum’s exhibition plans solidified, so too did our desire for certain artifacts. We didn’t know all the things we needed, but I knew we would eventually find them if we were creative in our search.

Early in my career, I did a great deal of community-driven collecting. I had stopped counting the times when I was in somebody’s house drinking tea with a senior citizen who suddenly pulled out an amazing artifact. As director of this museum, I believed that all of the 20th century, most of the 19th, maybe even a bit of the 18th might still be in trunks, basements and attics around the country. I also knew that as America changed, family homesteads would be broken up and heirlooms would be at risk. We had to start collecting now, because the community’s material culture might no longer exist in ten years.

So we created a program, “Saving African-American Treasures,” where we went around the country, invited people to bring their things in and taught them how to preserve them, free of charge. The first time we did it, in Chicago, on a brutally cold day, people actually waited in line outside the Chicago Public Library to show their treasures to the museum staff. We partnered with local museums, which gave them visibility and the opportunity to collect items of local importance. And we made sure the local congressman or -woman had a chance to be photographed holding an artifact so their picture could appear in the newspaper. This stimulated a conversation that encouraged people to save the stuff of their family’s history.

Our hopes were more than met. At that Chicago event, a woman from Evanston, Illinois, brought in a white Pullman porter’s hat. The white hat was very special—you had to be a leader of the porters to warrant the hat—and I had never seen one outside of a photograph before. When the woman offered to donate the hat, I was exhilarated, because while we always knew we were going to tell the story of the Pullman porters, this artifact would let us tell it in a different way.

As a result of the visibility that came from the treasures program, a collector from Philadelphia called me to say he had received material from a recently deceased relative of Harriet Tubman, the abolitionist and Underground Railroad conductor. As a 19th-century historian, I knew that the chances were slim that he had actual Tubman material, but I figured it was a short train ride from D.C. to Philadelphia and I could get a cheesesteak in the bargain. We met in a room at Temple University. And he reached into a box and pulled out pictures of Harriet Tubman’s funeral that were quite rare. By the time he pulled out a hymnal that contained so many of the spirituals that Tubman used to alert the enslaved that she was in their region, everyone was crying. I cried not only because these things were so evocative, but also because the collector was generous enough to give them to us.

As we hired more curators, we relied more on their collecting skills than on people bringing their things to us. We had a broad notion of the stories we wanted to tell, but not of the artifacts that would determine how we could tell them. We knew we wanted to talk about the role of women in the struggle for racial equality, but we didn’t know that we’d be able to collect a 1910 banner from the Oklahoma Colored Women’s Clubs that says, “Lifting As We Climb.”

Other individuals donated robes that had belonged to the Ku Klux Klan, including one that had been used by Stetson Kennedy, who infiltrated the Klan to write the book I Rode With the Klan in 1954. These and other potentially inflammatory artifacts pressed the question of how we could display them without coming off as exploitive, voyeuristic or prurient. Our answer was: Context was everything. No artifact would be off-limits, as long as we could use it to humanize the individuals involved and illustrate the depth of the struggle for equal rights.

The curators operated under one firm directive: 70 to 80 percent of what they collected had to end up on the museum floor, not in storage. We couldn’t afford to collect, say, a thousand baseballs and have only two of them end up on display. Sometimes I had to be convinced. One curator brought in a teapot—a nice teapot, but it was just a teapot to me, and it was going to take some money to acquire it. Then the curator pointed out that this teapot bore the maker’s mark of Peter Bentzon, who was born in St. Croix and made his way to Philadelphia at the end of the 18th century. And that even though his name meant a lot to people who study the decorative arts, this was only like the fourth example of his work known to exist. So suddenly I saw it not as a teapot, but as the concrete expression of somebody who was born enslaved, got his freedom, carved out economic opportunities and developed a level of craftsmanship that is spectacular to this day.

As we kept collecting, we ran across things I didn’t expect, like Nat Turner’s Bible and Roy Campanella’s catcher’s mitt. And the surprises continued to shape our collecting. It turned out that Denyce Graves owned the dress Marian Anderson wore when she sang her historic concert at the Lincoln Memorial in 1939; after Ms. Graves sang at our groundbreaking ceremony in 2012, she was moved to donate the dress to us. Chuck Berry offered us the guitar he wrote “Maybelline” on—as long as we’d take his cherry-red 1973 Cadillac Eldorado, too. That donation was shaky until one of our staff members went out to see him in Missouri and sealed the deal over ice cream sandwiches. George Clinton parted with his fabled P-Funk Mothership, which brings home for me how his stagecraft expressed his yearning to get beyond a society riven by racial strife.

The one thing I was intent on getting was something tied to the slave trade. I knew it would be impossible to get an entire slave ship, but I just wanted a piece of one, almost like a relic or icon. I figured, how hard could it be? I called museums I knew around the country. Nothing. I called museums around the world. Same thing. But I found out that no one had ever done an archaeological documentation of a vessel that foundered while carrying a cargo of enslaved persons.

It took us several years and a few false starts, but then scholars at George Washington University pointed us toward the São José, which sank off South Africa in 1794. About 200 of the enslaved people aboard died and maybe 300 were rescued, only to be sold in Cape Town the next week. To document that vessel, we started the Slave Wrecks Project with more than half a dozen partners, here and in South Africa. We trained divers, and we found documents that allowed us to track the ship from Lisbon to Mozambique to Cape Town. And we identified the region in Mozambique where the enslaved people it was carrying, the Makua, had come from.

It was inland, and it had something I’d never seen before—a ramp of no return, which enslaved people had to walk down to get to a boat that would take them away. It was nothing like the Doors of No Return that I had seen at Elmina in Ghana or on Gorée Island in Senegal; it was just this narrow, uneven ramp. I was struck by how hard it was for me to keep my balance walking down the ramp and how it must have been so difficult walking in shackles. I kept looking at the beauty of the water before me but realized that those enslaved people experienced not beauty but the horror of the unknown.

We wanted to take some dirt from this village and sprinkle it over the site of the wreck, to symbolically bring the enslaved back home. The local chiefs were only too happy to oblige, giving us this beautiful vessel encrusted with cowry shells to hold the dirt. They said, “You think it’s your idea that you want to sprinkle the soil, but this is the idea of your ancestors.”

The day of our ceremony was horrible: driving rain, waves pushing all kinds of things onto the rocks, probably like the day the São José sank. We were packed into this house overlooking the wreck site; speeches were made and poems read. And then we sent our divers out toward the site to cast the dirt on the water. As soon as they finished, the sun came out and the seas went calm.

It sounds like a B-movie, but it was one of the most moving moments of my career. All I could think was: Don’t mess with your ancestors. I am so honored and humbled to display remnants of the ship at the National Museum of African American History and Culture.

**********

It is impossible to overstate how meaningful it is to have this museum on the National Mall. Historically, whenever Congress directed the Smithsonian to build a museum, it specified where. We were given four possible sites. I spent a year having them analyzed on the basis of cost, water supply, truck access, pedestrian flow and all the other nuts-and-bolts issues that come with any big construction project. But there was one other factor that comes with no other project—the sensitivity over what is built on the Mall.

This might seem a little opaque to non-Washingtonians, but the Mall—America’s front yard—is hallowed ground. It is where the world comes to better understand what it means to be an American. It is where the March on Washington drew multitudes in 1963, and where Marian Anderson’s voice overrode the strains of discrimination that Easter morning in 1939. There was a feeling, amply expressed, that the Mall was already overbuilt and that this museum had to go somewhere else; another view, also amply expressed, was that this museum was so important it could go nowhere else.

I spent months evaluating the sites with my deputy director, Kinshasha Holman Conwill. To me, the issue was, which one was best suited to house a national museum that would present a history little known and often undervalued to the millions who visit the Smithsonian Institution? Of the four on the list, the two that were off the Mall would have involved the added cost of razing pre-existing buildings, rerouting highways and relegating an important history far from the mainstream of Washington visitation. One of the sites on the Mall already had a Smithsonian facility on it, the Arts and Industries Building, but it needed a major renovation. I believed it would be a lot harder to raise money to refurbish an older building than to create something new and distinctive.

After reviewing the choices, I felt that the five-acre site at 14th Street and Constitution Avenue NW was the best possible location for this museum. There were meetings, reports, hearings and dueling letters in the newspapers—“contentious” doesn’t begin to describe it. But in January 2006, the Smithsonian regents voted to put the museum on the Mall, next to the Washington Monument and within the shadow of the White House.

“My first task for tomorrow is to stop smiling,” I said. I have no clear memory of saying it, but I must have. It became the Quotation of the Day in the New York Times.

I knew I wanted the building to be environmentally green, to enhance the Washington landscape, and to reflect spirituality, uplift and resiliency. Of course it had to be functional as a museum, but I had no idea what it should look like—just not like another marble Washington edifice. Early on I received an array of packets from architects asking to design the museum, so I knew there would be global interest in this commission. But questions abounded: Did the architect have to be a person of color? Should we consider only architects who had built museums or structures of this cost or complexity? Was the commission open only to American architects?

I felt it was essential that the architectural team demonstrate an understanding of African-American culture and suggest how that culture would inform the building design. I also felt that this building should be designed by the best team, regardless of race, country of origin or the number of buildings it had built.

More than 20 teams competed; we winnowed them down to six finalists. Then I set up a committee of experts, from both inside and outside the Smithsonian, and asked the competing teams to submit models. Then I did something that some of my colleagues thought was crazy: We displayed the models at the Smithsonian Castle and asked members of the museum-going public to comment on them. The perceived danger was that the committee’s choice might be different from the visitors’ favorite. For the sake of transparency, I was willing to take that risk. I wanted to be sure that no one could criticize the final choice as the result of a flawed process.

Choosing the architectural team made for some of the most stressful weeks I’ve had in this job. After all, we would have to work together, dream together and disagree together for ten years. We had a unique chance to build something worthy of the rich history of black America. And we had more than half a billion dollars at stake. But those weeks were also some of my most enlightening, as some of the world’s best architects—Sir Norman Foster, Moshe Safdie, Diller Scofidio + Renfro and others—described how their models expressed their understanding of what we wanted.

My favorite was the design from a team led by Max Bond, the dean of African-American architects, and Phil Freelon, one of the most productive architects in America. Max’s model also received favorable reviews in the public’s comments. After very rigorous and candid assessments, that design became the committee’s consensus choice. Unfortunately, Max died soon after we made the selection, which elevated David Adjaye, who was born in Tanzania but practices in the United Kingdom, to be the team’s lead designer.

The design’s signature element is its corona, the pierced bronze-colored crown that surrounds the top three levels of the exterior. It has an essential function, controlling the flow of sunlight into the building, but its visual symbolism is equally important. The corona has roots in Yoruban architecture, and to David it reflects the purpose and the beauty of the African caryatid, also called a veranda post. To me, there are several layers of meaning. The corona slopes upward and outward at an angle of 17 degrees, the same angle that the Washington Monument rises upward and inward, so the two monuments talk to each other. We have a picture from the 1940s of black women in prayer whose hands are raised at this angle, too, so the corona reflects that facet of spirituality.

The most distinctive feature of the corona is its filigree design. Rather than simply piercing the corona to limit the reflective nature of the material, I wanted to do something that honored African-American creativity. So I suggested that we use the patterns of the ironwork that shapes so many buildings in Charleston and New Orleans—ironwork that was done by enslaved craftsmen. That would pay homage to them—and to the unacknowledged labor of so many others who built this nation. For so long, so much of the African-American experience has remained hidden in plain sight. No more.

**********

Once you’re inside our museum, you will be enveloped by history. Exhibitions will explore the years of slavery and freedom, the era of segregation and the stories of recent America. On another floor you will explore the notion of community in exhibitions that examine the role of African-Americans in the military and in sports—and you’ll understand how the power of place ensured that there was never one single African-American experience. The last exhibition floor explores the role of culture in shaping America, from the visual arts to music to film, theater and television.

The stuff of history will be your guide, whether it’s an actual slave cabin reconstructed near a freedman’s cabin, or a railroad car outfitted for segregated seating, or the dress Carlotta Walls’ parents bought for her to wear the day in 1957 she and eight others integrated Central High School in Little Rock, or a rescue basket used after Hurricane Katrina. There are nearly 4,000 artifacts to explore, engage and remember, with more in storage until they can be rotated into the museum.

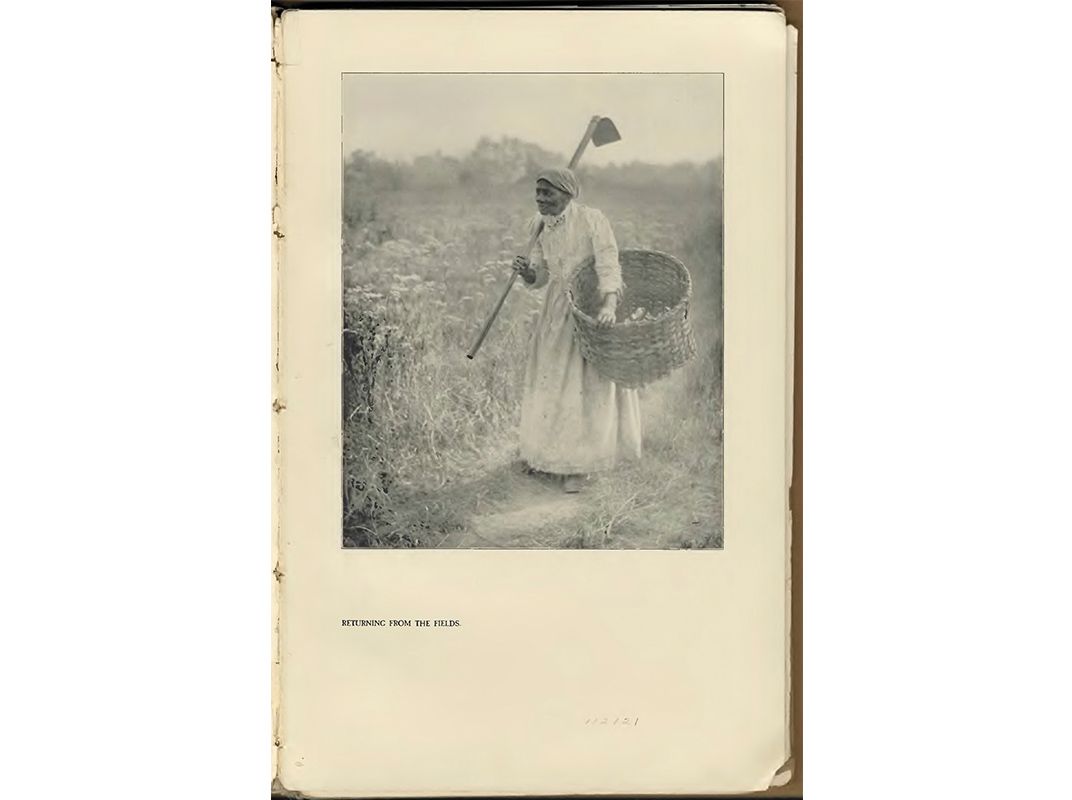

When I move into my new office, the one object that I will bring with me is a photograph I’ve kept on my desk for years, one taken in the late 1870s of an African-American woman who was once enslaved. I was drawn to the image because her diminutive stature reminded me of my grandmother. She’s walking up a slight incline. In one arm she holds a garden hoe that is taller than she is. In her other arm she cradles a basket used for harvesting corn or potatoes. Her hair is wrapped neatly, but her dress is tattered. Her knuckles are swollen, probably from years of labor in the fields. She is clearly weary, but there is pride in her posture, and she is moving forward despite all she is carrying.

This image became my touchstone. Whenever I get tired of the politics, whenever the money seems like it will never come, whenever the weight of a thousand deadlines feels crushing, I look to her. And I realize that because she did not quit, I have opportunities she could never imagine. And like her, I keep moving forward.

Building the National Museum of African American History and Culture

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lonnie_new1.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c0/9d/c09d4436-ebaf-4e88-96c2-eb982477e111/sep2016_k05_lonniebunch.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lonnie_new1.jpg)