“Call Me Ishmael” Is the Only Melville Tradition in This Innovative Presentation of “Moby Dick”

Visceral, kinesthetic, cinematic, aural and psychological, Arena Stage’s new show about the 19th-century novel is a 21st-century experience

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/cb/38/cb385137-dc84-49d8-a611-72bc34d756f1/hiresmobydick01web.jpg)

“Call me Ishmael.” So begins Arena Stage’s current presentation of the play Moby Dick. But after that familiar line, this highly engaging production shrugs off tradition with strobe lights flashing, giant waves crashing and the audience swept up in a relentless sense of movement. The play has become an "experience" of life aboard the Nantucket whaler Pequod with Capt Ahab in pursuit of the white whale Moby-Dick.

Arriving at Arena from Chicago’s Lookingglass Theatre Company and with an upcoming stop at South Coast Repertory in Cosa Mesa, California in January, Moby Dick is the product of a multidisciplinary group that received the 2011 Tony Award for Outstanding Regional Theatre.

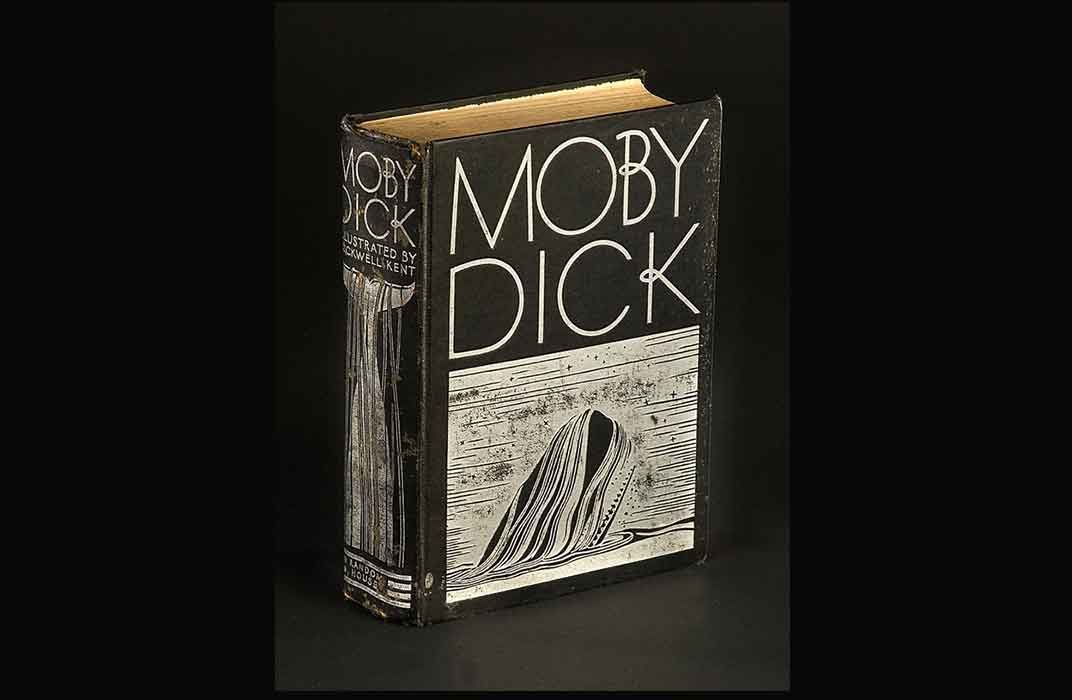

Founded in 1988, the company is dedicated to creating original, story-centered theater through physical and improvisational techniques. For this production, playwright-director and founding member David Catlin was inspired by the challenge of transforming Herman Melville’s lengthy 1851 novel into a compact 21st-century production that reflects the pace and interaction demanded by today’s audiences.

As a faculty member of Northwestern University, Catlin calls himself a “theater-maker who acts, writes, directs and teaches.” Since Lookingglass was created, he has been part of more than 50 world premieres, and currently serves as the company’s director of artistic development.

Traditional “static theater” is dead-in-the-water to today’s theatergoers who are “used to interacting with multiple screens” and multitasking, says Catlin. So the idea for Moby Dick was to dramatically reimagine Melville’s classic seafaring tale, strip it of convention, and make it pulsate with bold acrobatics.

“We refer to the stage as the deck,” Catlin says, and “the people working back stage are the crew.”

He appreciates that theater has long been a primarily auditory experience. “In Shakespearean England, you wouldn’t go to see a play, you’d go to hear a play,” he says, referring to the rich language and iambic rhythms of Elizabethan theater.

While he respects that tradition, Catlin wants to experiment with a type of theater that people “can experience in other ways, too.”

Lookingglass continually innovates with a performance style that shapes an immersive audience environment. Their method incorporates music, circus, movement, puppetry and object animation, symbol and metaphor, and visual storytelling to create work that is visceral, kinesthetic, cinematic, aural and psychological.

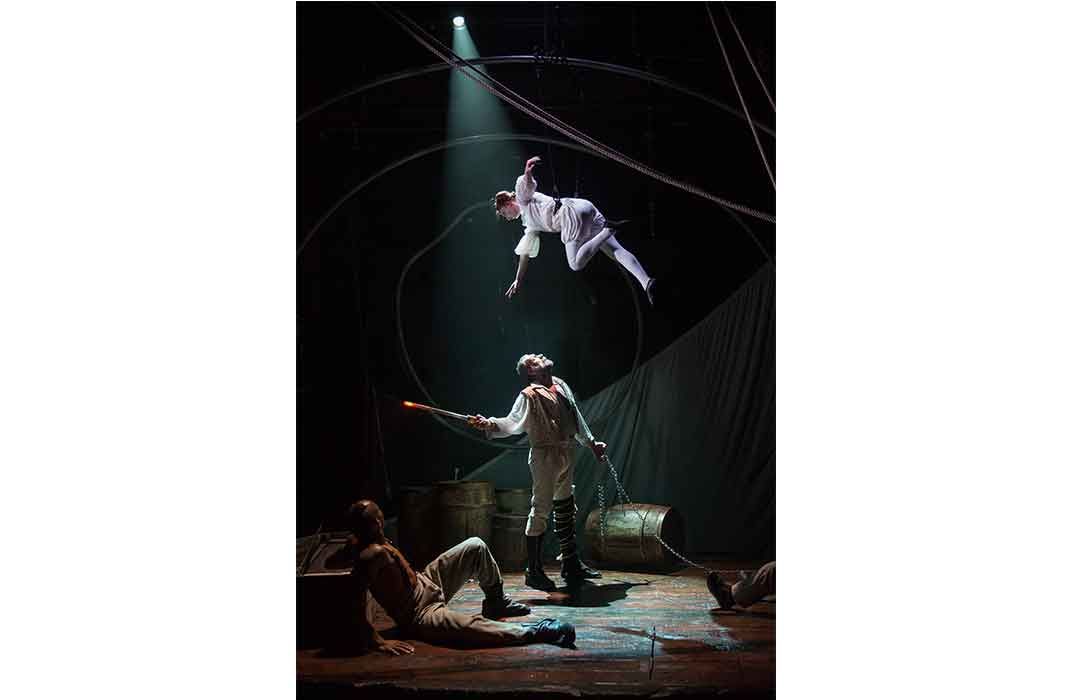

The company collaborated with The Actors Gymnasium, in Evanston, Illinois, one of the nation’s premier circus and performing arts training centers. Actors tell their stories acrobatically, propelling themselves across a set designed as a ship’s deck. Filled with interlocking cables and rope riggings, the entire stage, or deck, is framed by arching steel-tubed pipes suggesting the curved ribs of a whale. The set, says Catlin, conveys the long connection between theater and ships—many of the mechanical elements used to move theatrical scenery are common to sailing, such as the block and tackle used to raise and lower curtains, and the use of rope lines.

This production of Moby Dick with its daring use of circus techniques plays to a shared history with the book’s origins.

Herman Melville published Moby Dick in a decade that’s been called “the golden age of the circus.” The circus was considered America’s most popular form of entertainment in the mid-19th century, and master showman P.T. Barnum even established his American Museum as a proto-circus on Broadway, winning great notoriety by displaying such wildly diverse entertainments as “industrious fleas, automatons, jugglers, ventriloquists….”

While Melville never met Barnum, he was certainly aware of the circus and wrote about it evocatively in his short story “The Fiddler,” published anonymously in Harper’s in 1854. The story depicts a sad poet being cheered up by a friend who takes him to a circus: he is swept up by “the broad amphitheater of eagerly interested and all-applauding human faces. Hark! claps, thumps, deafening huzzas; one vast assembly seemed frantic with acclamation. . . .”

The stage audience experiences circus and movement, says Catlin, “in a visceral and kinesthetic and muscular way.” Some of the performers are circus-trained, adding authenticity to the aerial acrobatics displayed.

“The dangers of sailing and whaling are made that much more immediate,” he says, “when the performers are engaged in the danger inherent in circus.”

Using movement to propel the art of storytelling is an increasingly popular theatrical approach. Earlier, modern dance pioneers occasionally incorporated a mix of artistic and theatrical ingredients; Martha Graham notably had a brilliant 40-year collaboration with sculptor Isamu Noguchi that resulted in 19 productions. A photograph of Noguchi’s “Spider Dress” for Graham is currently on display in the Smithsonian American Art Museum’s new exhibition, "Isamu Noguchi, Archaic/Modern."

Choreographer Christopher Wheeldon is contemporary ballet’s leading proponent of storytelling through movement, and has applied his flowing narrative approach both to classical ballet and to Broadway, where his production of An American in Paris won a 2015 Tony Award.

Perhaps the singular, most dramatic example of a company that tells stories through movement is the Synetic Theater in Arlington, Virigina, which is renowned for its fluid synthesis of innovative techniques for silent storytelling using only mime and movement.

Moby Dick has inspired countless adaptations: Orson Welles broadcast a 1946 radio version, Gregory Peck starred in a 1956 film, Cameron Mackintosh produced a 1992 musical that became a West End hit, and there was a 2010 Dallas Opera production that was a box office triumph.

The Lookingglass production of Moby Dick taps into the public’s continuing fascination for the classic novel with a grand and obsessive vengeance, but Lookingglass employs a more intimate approach.

The company creates a small-scale immersive theatrical experience that largely succeeds, although coherent storytelling in Act II sometimes loses out to vivid theatricality. The costume designs are highly imaginative—actors opening-and-closing black umbrellas seem perfectly credible as whales spouting alongside the Pequod, and the humongous skirt of one actor magically flows across the stage/deck in giant wave-like ocean swells.

Ahab’s doom is never in doubt, and we are there for every vengeful step. For David Catlin, the set’s rope riggings convey the play’s essential metaphor: the web they weave provides the “aerial story-telling” that connects Ahab to his fate, and the rest of us “to each other.”

Moby Dick is a co-production with The Alliance Theatre and South Coast Repertory. It will be in residence at Arena Stage through December 24, before heading to the South Coast Repertory in Cosa Mesa, California, January 20 through February 19, 2017.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Amy_Henderson_NPG1401.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Amy_Henderson_NPG1401.jpg)