Bronze Sculptures of Five Extinct Birds Land in Smithsonian Gardens

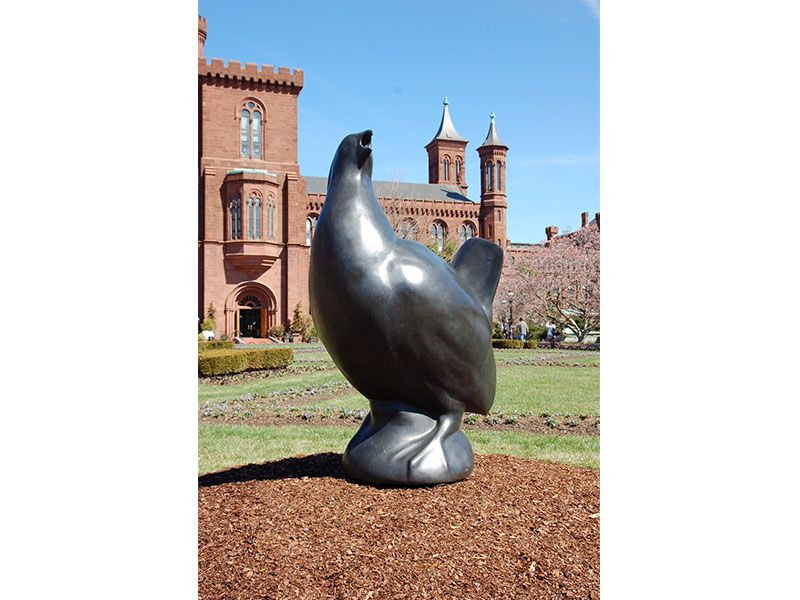

Artist Todd McGrain memorializes species long-vanished, due to human impact on their habitats, in his “Lost Bird Project”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/2a/34/2a3418af-9ea8-4b3a-b696-bad7bd41a8d7/lbp_set3-credit_the_lost_bird_project.jpg)

It has been almost 15 years since artist Todd McGrain embarked on his Lost Bird Project. It all began with a bronze sculpture of a Labrador duck, a sea bird found along the Atlantic coast until the 1870s. Then, he created likenesses of a Carolina parakeet, the great auk, a heath hen and the passenger pigeon. All five species once lived in North America, but are now extinct, as a result of human impact on their populations and habitats.

McGrain's idea was simple. He would memorialize these birds in bronze and place each sculpture in the location where the species was last spotted. The sculptor consulted with biologists, ornithologists and curators at natural history museums to determine where the birds were last seen. The journal of an early explorer and egg collector pointed him toward parts of Central Florida as the last-known whereabouts of the Carolina parakeet. He followed the tags from Labrador duck specimens at the American Museum of Natural History to the Jersey shore, Chesapeake Bay, Long Island and ultimately to the town of Elmira, New York. And, solid records of the last flock of heath hens directed him to Martha's Vineyard.

McGrain and his brother-in-law, in 2010, took to the road to scout out these locations—a rollicking roadtrip captured in a documentary called The Lost Bird Project—and negotiated with town officials, as well as state and national parks, to install the sculptures. His great auk is now on Joe Batt's Point on Fogo Island in Newfoundland; the Labrador duck is in Brand Park in Elmira; the heath hen is in Manuel F. Correllus State Forest in Martha's Vineyard; the passenger pigeon is at the Grange Audubon Center in Columbus, Ohio; and the Carolina parakeet is at Kissimmee Prairie Preserve State Park in Okeechobee, Florida.

McGrain is no stranger to the intersection of art and science. Before focusing on sculpture at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, he studied geology. "I've always thought that my early education in geology was actually my first education in what it means to be a sculptor. You look at the Grand Canyon and what you see there is time and process and material. Time and process and material have remained the three most important components in my creative life," he says. The Guggenheim fellow is currently an artist-in-residence at Cornell University's Lab of Ornithology. He says that while he has always had an interest in natural history and the physical sciences, these passions have never coalesced into a single effort the way they have with the Lost Bird Project.

Since deploying his original sculptures throughout the country, McGrain has cast identical ones that travel for various exhibitions. These versions are now on display in Smithsonian gardens. Four are located in the Enid A. Haupt Garden, near the Smithsonian Castle, and the fifth, of the passenger pigeon, is in the Urban Habitat Garden on the grounds of the National Museum of Natural History, where they will stay until March 15, 2015.

The sculpture series comes to the National Mall just ahead of "Once There Were Billions: Vanished Birds of North America," a Smithsonian Libraries exhibition opening at the Natural History Museum on June 24, 2014. The show, commerating the 100th anniversary of the death of Martha the passenger pigeon, the last individual of the species, will feature Martha and other specimens and illustrations of these extinct birds. The Smithsonian Libraries plans to screen McGrain's film, The Lost Bird Project, and host him for a lecture and signing of his forthcoming book at the Natural History Museum on November 20, 2014.

What were your motivations? What inspired you to take on the Lost Bird Project?

As a sculptor, most everything I do starts with materials and an urge to make something. I was working on the form of a duck, which I intended to develop into a kind of an abstraction, when Chris Cokinos’ book entitled, Hope is the Thing With Feathers, sort of landed in my hands. That book is a chronicle of his efforts to come to grips with modern extinction, particularly birds. I was really moved. The thing in there that really struck me was that the Labrador duck had been driven to extinction and was last seen in Elmira, New York, in a place called Brand Park. Elmira is a place I had visited often as a child, and I had been to that park. I had no idea that that bird was last seen there. I had actually never even heard of the bird. I thought, well, as a sculptor that is something that I can address. That clay study in my studio that had started as an inspiration for an abstraction soon became the Labrador duck, with the intention of placing it in Elmira to act as a memorial to that last sighting.

How did you decide on the four other species you’d sculpt?

They are species that have all been driven to extinction by us, by human impact on environmental habitat. I picked birds that were driven to extinction long enough ago that no one alive really has experienced these birds, but not so far back that their extinction is caused by other factors. I didn’t want the project to become about whose fault it is that these are extinct. It is, of course, all of our faults. Driving other species to extinction is a societal problem.

I picked the five because they had dramatically different habitats. There is the prairie hen; the swampy Carolina parakeet; the Labrador duck from someplace like the Chesapeake Bay; the Great Auk, a sort of North American penguin; and the passenger pigeon, which was such a phenomenon. They are very different in where they lived, very different in their behaviors, and they also touch on the primary ways in which human impact has caused extinction.

How did you go about making each one?

I start with clay. I model them close to life-size in clay, based on specimens from natural history museums, drawings and, in some cases, photographs. There are photographs of a few Carolina parakeets and a few heath hens. I then progressively enlarge a model until I get to a full-size clay. For me, full-size means a size that we can relate to physically. The scale of these sculptures has nothing to do with the size of the bird; it has to do with coming up with a form that we meet as equals. It is too big of a form to possess, but it’s not so big as to dominate, the way that some large-scale sculptures can. From that full-scale clay, basically, I cast a wax, and through the process of lost wax bronze casting, I transform that original wax into bronze.

In lost wax casting, you make your original in wax, that wax gets covered in a ceramic material and put into an oven, the wax burns away, and in that void where the wax once was you pour the molten metal. These sculptures are actually hollow, but the bronze is about a half an inch thick.

Why did you choose bronze?

It is a medium I have worked in for a long time. The reason I chose it for these is that no matter how hard we work on material engineering bronze is still just this remarkable material. It doesn’t rust. It is affected by the environment in its surface color, but that doesn’t affect its structural integrity at all. So, in a place like Newfoundland, where the air is very salty, the sculpture is green and blue, like a copper roof of an old church. But, in Washington, those sculptures will stay black forever. I like that it is a living material.

What impact did placing the original sculptures in the locations where the species were last spotted have on viewers, do you think?

I think what would draw someone to these sculptures is their contour and soft appealing shape. Then, once that initial appreciation of their sculptural form captures their imagination, I would hope that people would reflect on what memorials are supposed to do, which is [to] bring the past to the present in some meaningful way. In this way, I would think the sculpture's first step is to help you recognize that where you are standing with this memorial is a place that has a significance in the natural history of this country and then ultimately ask the viewer to give some thought to the preciousness of the resources that we still have.

Has ornithology always been an interest of yours?

I am around too many ornithologists to apply that label to myself. I would say I’m a bird lover. Yeah, I think birds are absolutely fantastic. It is the combination that really captures my imagination; it is the beautiful form of the animals; and then it is the narrative of these lost species that is really captivating.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)