Breakthrough Korean Feminist Artist Yun Suknam in Her First U.S. Museum Exhibition

With an assemblage portrait of her mother as the focal piece, the artist’s work is surrounded by the works of those who inspired her

:focal(923x876:924x877)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/aa/a8/aaa8b3f5-1d51-4e67-bf91-7f45b138b15b/ysn_82963.jpg)

The whole idea behind the “Portraits of the World” series, at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery, is to shine a light on international art and put it into context with American pieces in the museum’s collections.

So far, the centerpiece artwork is not as well known in the United States as it is in its homeland. But in Korea, Yun Suknam, now 80, is highly regarded as a pioneering figure in feminist art and her newly exhibited piece at the Portrait Gallery, Mother III harkens back to her breakthrough solo 1993 show, “The Eyes of Mother” that debuted in Seoul.

According to organizing curator Robyn Asleson, Yun had a very traditional life as a wife and mother. “At the age of 40, she had this kind of awakening similar to what a lot of American women had in the 1960s and 70s of thinking—‘I have no identity apart from being a wife and mother.’ She wanted to find herself and discover what she was meant to do with her life,” says Asleson, pointing out that Yun always wanted to be an artist. But the hard, economic realities of postwar Korea meant that she had to put away those ideas.

Yun started studying calligraphy, drawing and painting, and her supportive husband encouraged her to study art in New York.

“That was a real turning point in her life—to see pop art, to see Louise Bourgeois’ assemblages made of steel cylinders and disused gasoline storage tanks, and all the remarkable things happening in New York in 1983 and on her return visit in 1991,” Asleson says. “That really showed her art could pop off the wall, it didn’t have to be flat, it didn’t have to be on paper or on silk, it could be made from materials that you could scavenge from the streets. So, her work became quite a turning point for feminist art, and art in general in Korea.”

A further innovation was Yun's decision that women would be her main subject, beginning with a series of portraits of her mother, Asleson says. “And by understanding her mother, she was really understanding the way women existed in Korean society traditionally.”

That exhibition, “The Eyes of Mother” traced the life of her mother Won Jeung Sook from the age of 19 to 90. “It was really a biographical show—that was in a way autobiographical as well,” Asleson says. “She said, by representing my mother, I’m representing myself.’”

The original Mother was put together with found wood, whose grains reflected the careworn wrinkles on elderly women. The pieces of a real wooden chair represent a chair in the work; the grain also suggesting folds of her drapery.

“The original sculpture from 1993 is what we originally had hoped to exhibit,” Asleson says. “But because it’s all very weathered, aged wood, the pieces were too fragile to travel to America and be here for a year.”

Bringing it to the U.S. for exhibition was seen as a lost cause, “but the artist really wanted to participate and thought that the 25th anniversary of this exhibition was a nice time to create a commemorative work that could be shown at the Portrait Gallery.”

The 2018 version of the work doesn’t use scraps she found in the streets, the curator says, “so it doesn’t have the same weathered softness and fragility of the original. I think it looks more stable. And she’s using the woodgrain to suggest the drapery, and the drapery folds, and she’s using it in slightly different ways—same idea, but different wood, so it looks a little bit different. But I think it’s just a little more polished.”

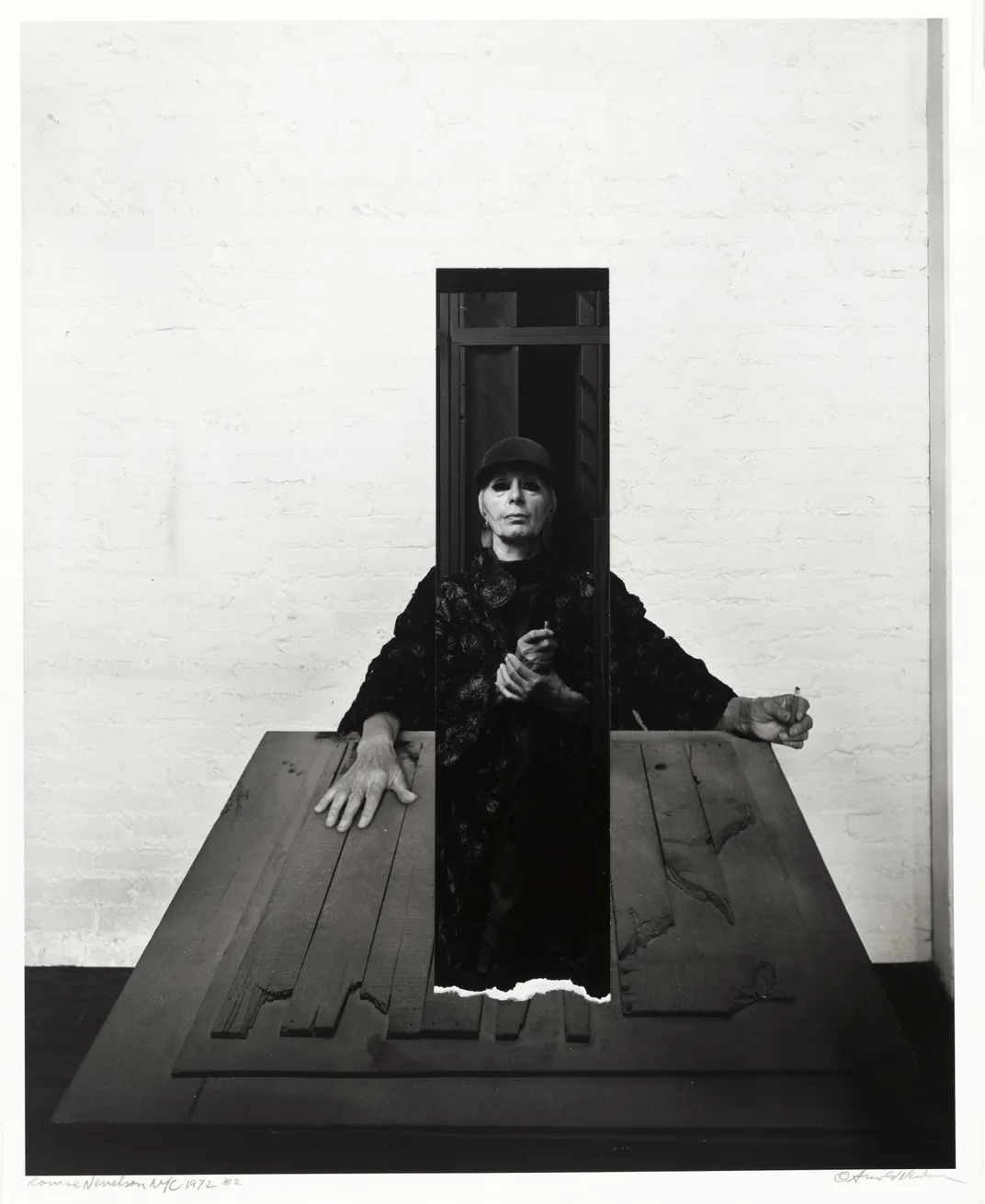

And now it rests, in the manner of the “Portraits of the World” exhibitions, among pieces and figures of U.S. artists who inspired her, or are otherwise suggested by her work. Nevelson is seen in a 1972 photograph by Arnold Newman; Bourgeois is represented in an intriguing triple self-portrait on paper.

Another artist who figures large in Yun’s development was the New York pop artist Marisol Escobar, known as Marisol, who is seen both in a photograph and in a large life-size wooden sculpture by Judith Shea that is presented opposite’s Yun’s work. (Marisol’s own work can also be seen on the third floor of the Portrait Gallery, amid work done for covers of Time magazine, that includes her wooden sculpture of Bob Hope).

Anh Duong’s large 2001 oil portrait of Diane von Fürstenberg, Cosmogony of Desire, was chosen not only because it is a portrait by a woman artist, but because of the emphasis on the penetrating eyes of the subject, the famous fashion designer.

“She began with one eye, and thought this was the key of understanding her subject, then typically works out from the eye,” Asleson says of Duong. “It ties into the idea of the women’s gaze and seeing the world through a woman’s eyes. . . . Similarly, Yun Suknam was trying to see the world through a mother’s eye, and also reversing traditional Korean portraiture convention by having the woman look directly at the viewer. Usually women’s eyes are averted politely and demurely in Korean art, but she felt very strongly that she wanted a direct gaze.

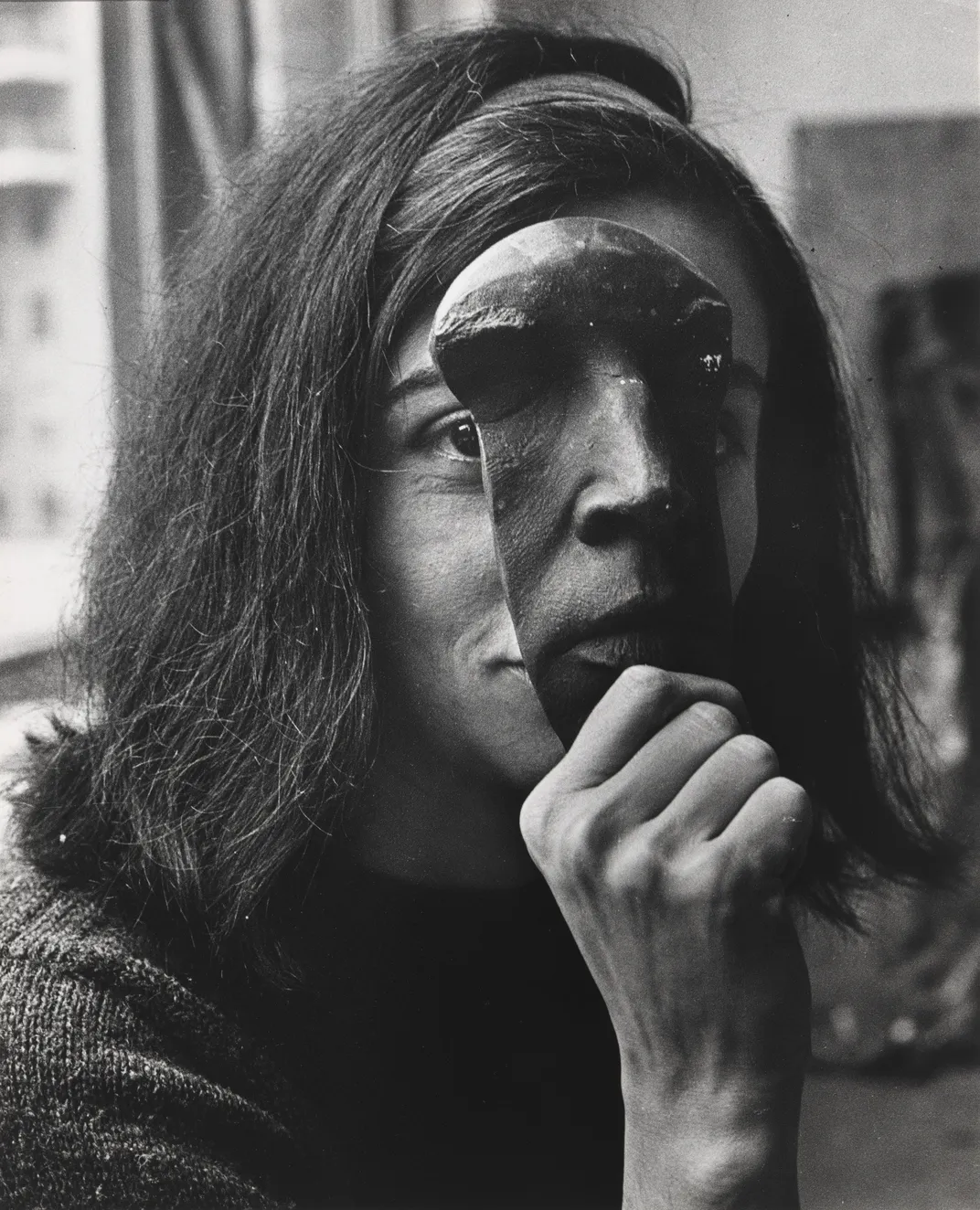

Masks play a role in a couple of the pieces as well, hiding the face of Marisol in a 1964 photograph by Hans Namath, and figuring in the Self-Portrait (On Being Female) by Pele de Lappe, a contemporary of Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo.

“They’re both coincidentally holding masks in front of their faces to call attention to the kinds of public social expectations that are imposed on people in general, but in particular on women. In that case, to look a certain way and to act a certain way that doesn’t necessarily reflect who they are,” Asleson says. “That’s tied into the borrowed piece from Korea.”

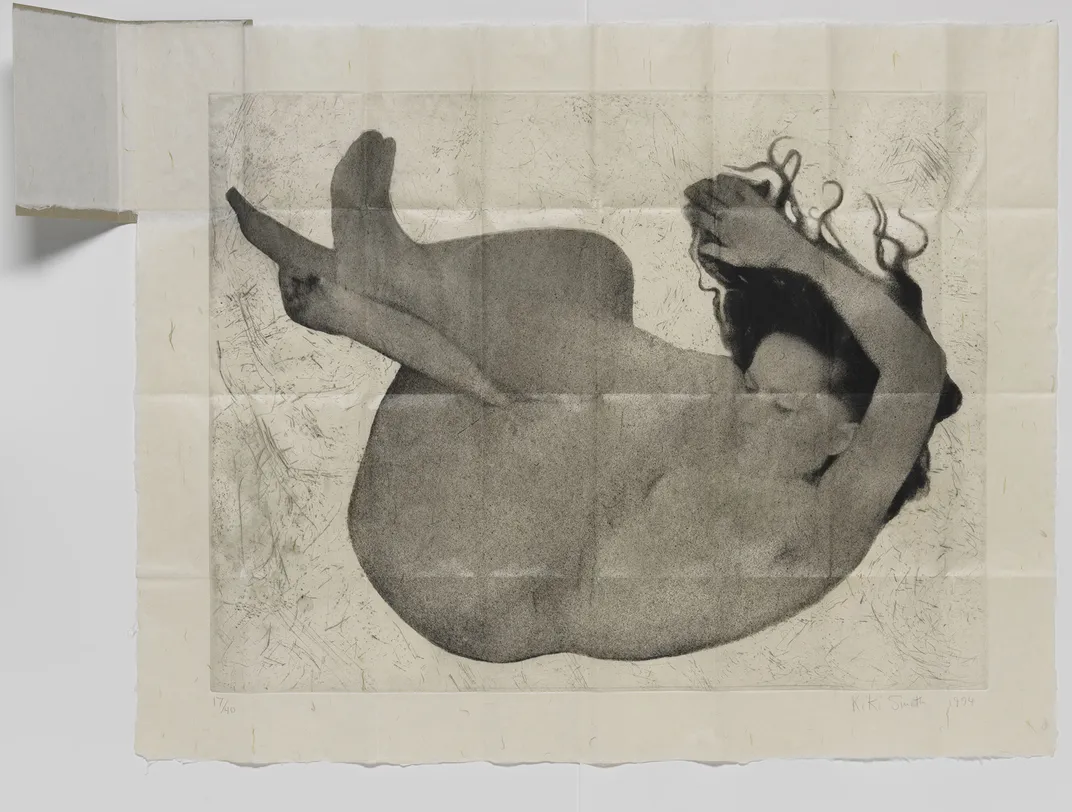

Kiki Smith, Nancy Spero and Ruth Ellen Weisberg round out the small show—which may be a draw simply because of its brevity.

The international focus, which began last year with “Portraits of the World: Switzerland,” built around a painting by Ferdinand Hodler, provides “a lens to look at the collection through a different perspective,” Asleson says. “We’re exhibiting a lot of things that haven’t been shown. They haven’t really fit into our permanent displays in other ways, but now as we’ve got this thematic emphasis, all of a sudden, it’s like: yes, all of this relates really closely. It makes a nice group.”

And such a way to display a theme may be a wave of the future at museums, she says. “I think people get exhausted and don’t have so much time, but to have a deep dive that is quick but very substantive I think is very appealing.”

It also is one of the first exhibitions among the Smithsonian museums to herald its ambitious American Women’s History Initiative, marking the 100th anniversary of women’s suffrage. “It’s a small start to a very big project,” Asleson says.

“Portraits of the World: Korea,” curated by Robyn Asleson, continues at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery through Nov. 17, 2019.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)