WWII Bunker Used by Churchill’s ‘Secret Army’ Unearthed in Scotland

British Auxiliary Units were trained to sabotage the enemy in case of German invasion

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c0/07/c007e99f-0e2e-4a46-8f1a-9cef5dff8dcc/2020_march10_secretbunker.jpg)

If the Nazis had invaded Great Britain during World War II, they would have faced an uprising of scallywags—specifically, the Auxiliary Units also known as Winston Churchill’s “secret army.” These elite fighters, chosen for their knowledge of the surrounding landscape, were among the United Kingdom’s last line of defense. Tasked with sabotaging enemy invaders, the men were trained to hide out in underground bunkers, lying in wait as the Nazis drove past before emerging to wreak havoc behind German lines.

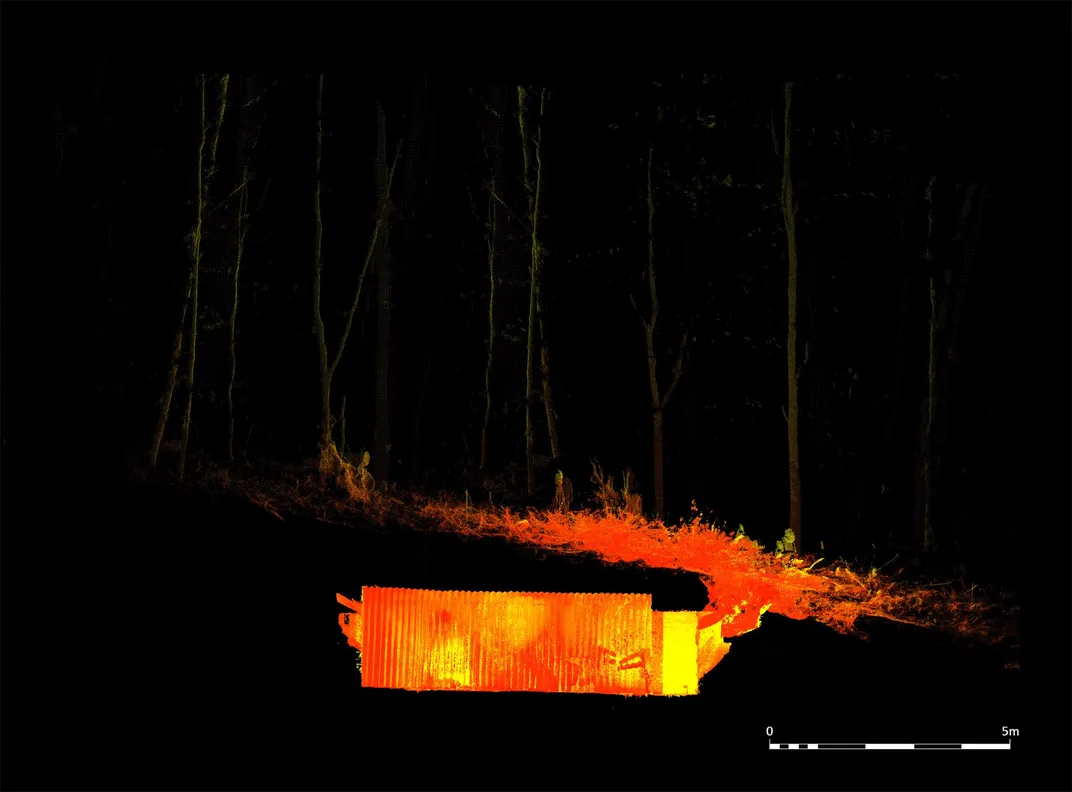

Researchers from Forestry and Land Scotland (FLS) unearthed one of these long-overlooked bunkers while conducting tree felling operations last month, according to a press release.

“This discovery gives us an insight into one of the most secretive units … operating during WWII,” FLS archaeologist Matt Ritchie tells the Scotsman’s Alison Campsie. “It’s quite rare to find these bunkers as their locations were always kept secret—most were buried or lost.”

Over the course of the war, auxiliary forces dug 500 secret bunkers across Britain. Per BBC News, these hideaways—accessed via a hatch entrance and left, if need be, by a rear escape hatch—measured about 23 feet long and 10 feet wide. Stocked with enough weapons and supplies to last around five weeks, the bunkers were equipped to house at least seven soldiers at a time.

Most of these bunkers’ specific locations are lost to history, as the men who built them signed the Official Secrets Act, which prohibited them from talking about their assignments for decades.

“We would never talk about what we were trained to do,” Trevor Miners, who was 16 years old when he volunteered with the Auxiliary Units in Oxfordshire, told BBC News in 2013. “One of my unit was even sent a white feather by someone who thought he was a coward for not going out to fight, but we knew different.”

Auxiliary teams were made up of locals who knew the land well, including gamekeepers, foresters and poachers, according to FLS. Per BBC News’ Nick Tarver, members were trained to destroy railway lines and enemy supplies, make homemade explosives, and carry out assassinations. They learned how to fashion weapons out of household objects and received instruction manuals disguised as mundane objects like fertilizer booklets and calendars.

In the event of invasion, auxiliary soldiers had an estimated life expectancy of just 10 to 14 days—in part, perhaps, because the bunkers were not as hidden as their inhabitants would have liked. On several occasions, courting couples strolling through the woods stumbled upon the men’s hideouts, forcing them to relocate.

Still, historian Tom Sykes told BBC News in 2013, the main factor in auxiliary units’ projected mortality rates was the fact that these soldiers “were signing up to a suicide mission.”

Added Sykes, “There was no way out for them, they were going to be caught and tortured, they were ready to kill themselves before allowing themselves to be captured.”

FLS survey technicians Kit Rodger and Kenny Bogle discovered the entrance to the bunker while surveying the area for heritage sites ahead of tree felling operations.

“The bunker was missing from our records, but as a child we used to play in these woods and visit the bunker, so I knew it was there,” says Rodger in the FLS statement. “With only vague memories of more than forty years ago, Kenny and I searched through head-high bracken until we stumbled on a shallow trench which led to the bunker door. Only a small opening remained, but we could just make out the blast wall in the darkness beyond.”

None of the beds, stove, table or other supplies once used by soldiers survive, though timbers left on the floor may have once been part of bedframes, per the Scotsman. For now, the bunker’s historical importance means its precise location will remain a secret—except, that is, to a select group of bats. Recognizing the bunker’s use as an artificial cave, FLS has installed boxes for the mammals to roost in.