Exhibition Re-Examines Modernism’s Black Models

Curator Denise Murrell looks at the unheralded black women featured in some of art history’s masterpieces

Édouard Manet’s “Olympia” is renowned for its subversive characteristics. The work, widely considered the modernist successor to Titian’s 1534 “Venus of Urbino,” depicts a prostitute boldly displaying her nude body to the viewer without a hint of modesty. But when Denise Murrell, then a graduate student at Columbia University, saw the painting appear onscreen during a lecture, she wasn’t interested in hearing her professor’s thoughts on the woman at the center of the canvas. Instead, she tells artnet News’ Naomi Rea, she wanted to discuss the second figure in the painting, a black servant who commands as much space as her white counterpart but is often ignored—which is exactly what happened that day in class.

The incident touched on a larger problem in her studies, Murrell realized: black women in art history were all-too-often rendered invisible. This frustration over the lack of scholarship surrounding black women in the art canon eventually led her to write a thesis entitled Posing Modernity: The Black Model from Manet and Matisse to Today. And that’s not all: As Hilarie M. Sheets reports for the New York Times, Murrell recently launched an exhibition of the same name at Columbia’s Wallach Art Gallery, drawing on more than 100 borrowed paintings, sculptures, photographs and sketches to present an unprecedented look at the unheralded women behind some of modernism’s greatest masterpieces.

The show, which is on view at Wallach through February 10, 2019, will travel to Paris’ Musée d’Orsay, longtime home of “Olympia,” in late March. Although the painting that inspired the exhibition isn’t included in the U.S. run, the New York Times’ co-chief art critic Roberta Smith notes that a larger-than-life reproduction—complemented by two of Manet’s preparatory etchings, as well as an array of lesser-known works by the Impressionist master and his contemporaries—is more than enough to drive Murrell’s point home.

Take Laure, the black woman who posed for “Olympia” and was actually depicted by Manet in two other works: “Children in the Tuileries Gardens,” which finds her consigned to the corner of the canvas as a nursemaid tending her charges at a Parisian park, and “La Négresse (Portrait of Laure),” a painting that places her at the center of attention. Manet’s notebooks reveal that he considered Laure, who lived a short walk away from his northern Paris studio, a “very beautiful black woman.”

She was one of many black individuals who moved to the area following France’s 1848 abolition of territorial slavery, Sheets writes, and was likely featured in “Olympia” as a nod to the city’s growing black working class.

Unlike the garish caricatures painted by Paul Gauguin and other 19th-century artists who bought into the myth of exotic “Orientalism,” Manet’s servant is just that: “She’s not bare-breasted or in the gorgeously rendered exotic attire of the harem servant,” Murrell tells Sheets. “Here she almost seems to be a friend of the prostitute, maybe even advising her.”

According to Artsy’s Tess Thackara, Manet’s 1863 “La Négresse (Portrait of Laure)” further highlights its model’s individuality, exhibiting a specificity of features unusual in its “departure from the dominant ethnographic lenses used to portray people of color.”

Black models from this period are represented in such works as Manet’s 1862 portrait of Jeanne Duval, an actress and singer best known as Charles Baudelaire’s mixed-race mistress. An 1879 pastel of mixed-race acrobat Miss Lala also veers from the stereotypical, showing the sense of fluid movement its creator, Edgar Degas, is known for. Another highlight from the late 19th century is the work of French photographer Nadar, who captures equestrian Selika Lazevski and Victorian matron Dolores Serral de Medina Coeli in a pair of elegant portraits that refuse to romanticize.

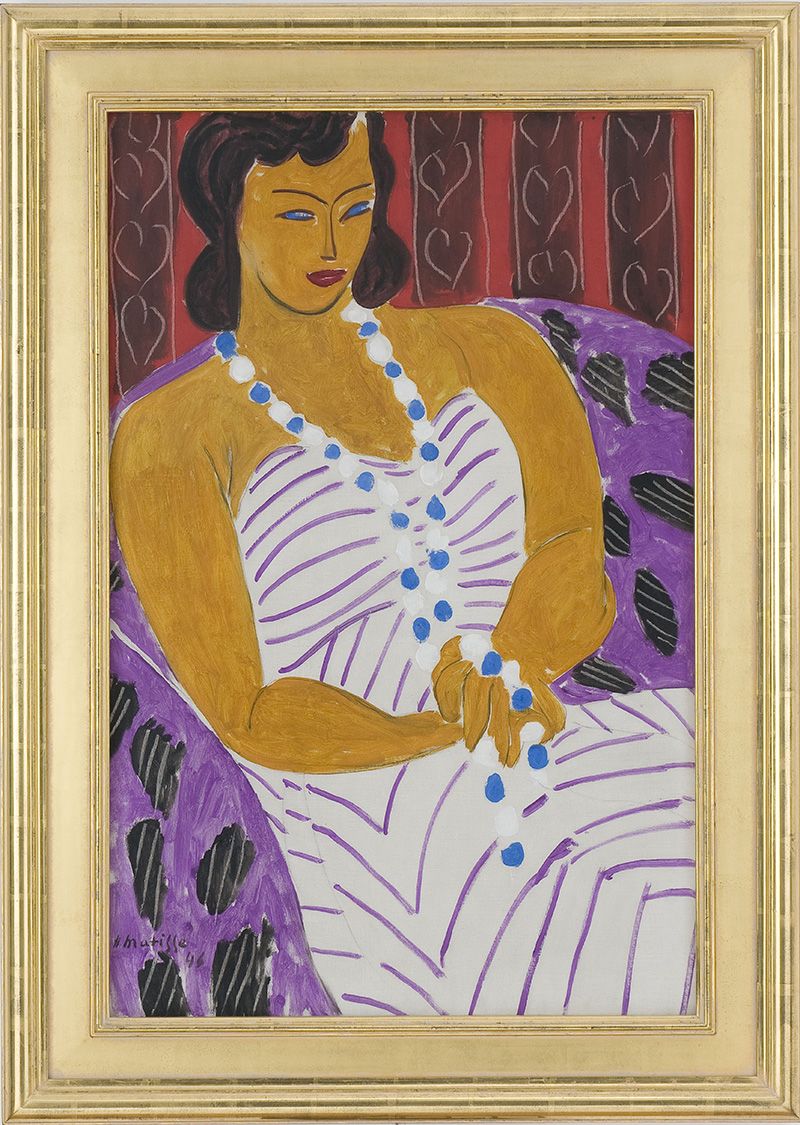

Posing Modernity continues its exploration with a jump to the 20th century. Murrell argues that Henri Matisse, one of the most egregious early practitioners of “Orientalism,” changed his style after visiting Harlem during the 1930s. But as Ariella Budick writes for the Financial Times, his 1940s drawings of Haitian dancer Carmen Lahens are “barely less perfumed, oscillating uneasily between abstraction and mythmaking.” Matisse’s 1946 portrait of mixed-race woman Elvire Van Hyfte falls victim to the same tendencies, Budick argues, rendering the “black model invisible [by] reclassifying her as a universal” female.

As the exhibition veers closer to the present, there’s an influx of black artists rendering black bodies: William H. Johnson, a Harlem Renaissance painter who the Guardian’s Nadja Sayej says specialized in capturing the everyday lives of African Americans; Romare Bearden, whose 1970 “Patchwork Quilt” combines “Olympia”’s prostitute and servant into one figure; and Mickalene Thomas, a contemporary artist who highlights her subject’s control over her sensuality in the 2012 work “Din, Une Très Belle Négresse.”

“You can see the evolution as the black figure comes closer to subjectivity, or agency, portrayed by women artists,” Murrell tells the Guardian, “or by showing black women in a way that’s closer to their own modes of self-representation.”

Come March, Posing Modernity will shift to the French stage with an expanded oeuvre featuring Manet’s original “Olympia.” As Laurence des Cars, director of the Musee d’Orsay, tells the Times’ Sheets, the arrival will offer a much needed re-examination of “the way we look at some very famous works of art.”

Posing Modernity: The Black Model from Manet and Matisse to Today is on view at Columbia’s Wallach Art Gallery through February 10, 2019 and at Paris’ Musée d’Orsay from March 26 to July 14, 2019.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)