This Week Has Offered a Slew of Insights on the Western Hemisphere’s First Humans

Studies reveal rapid yet uneven movement south in at least three migratory waves, complicating story of the Americas’ settlement

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/6f/4a/6f4a1a20-dcb0-4815-b24b-4a295948500f/natural_history_museum_of_denmark.jpg)

Scientists have come a long way since 2010, when researchers extracted DNA from a 4,000-year-old clump of hair to map out the first complete genome of an ancient human living in the Western Hemisphere. Today, that initial discovery has been supplemented by 229 genomes recovered from teeth and bone found across the Americas, providing geneticists with a comprehensive portrait of the region’s first inhabitants and their early migration patterns. Three new genomic studies published this week in Science, Cell and Science Advances fill in the details of ancient human migration in North and South America—and add some new twists and turns to their path.

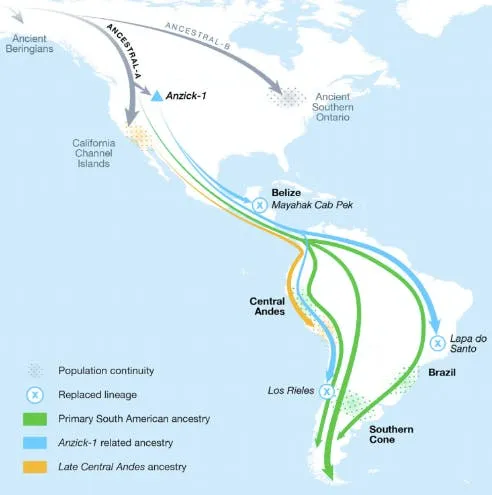

As Science News’ Tina Hesman Saey writes, the studies build on past findings to chart the path of the Americas’ first humans—who spread out from Siberia and East Asia to populate the northern and southern lands of North America before heading downward to South America—and hone in on a specific community based in the Andean Highlands between roughly 1,400 to 7,000 years ago. Summarizing the researchers’ extensive findings, George Dvorsky reports for Gizmodo that the new papers reveal rapid yet uneven movement south in at least three migratory waves beginning some 15,000 years ago, suggesting the individuals who settled the Americas were more genetically diverse than previously believed.

The Science study, led by Natural History Museum of Denmark researcher J. Víctor Moreno-Mayar, Southern Methodist University anthropologist David Meltzer, and University of Copenhagen and University of Cambridge evolutionary geneticist Eske Willerslev, draws on 15 ancient genomes—including that of a 9,000-year-old western Alaskan who is only the second Ancient Beringian to undergo DNA testing, according to The New York Times’ Carl Zimmer—to track early humans’ migration from Alaska to Patagonia, a region at the farmost tip of South America.

Science magazine’s Lizzie Wade writes that previous studies suggested the first Americans arrived from Siberia and East Asia about 25,000 years ago. While some stayed in the now defunct Beringia region, others moved south, splitting into two groups: Southern Native Americans and Northern Native Americans—who largely settled in what is now Canada and Alaska. The former spread across North and South America some 14,000 years ago, moving at what Meltzer describes as “astonishing speed” given their unfamiliarity with the landscape.

One of the most significant insights offered by the Science report is confirmation that a 10,700-year-old skeleton dubbed the “Spirit Cave mummy” is an ancestor of modern-day Native Americans, not a member of the “Paleoamericans” hypothesized to have populated North America before these native groups arose. As Hannah Devlin explains for The Guardian, the mummy, which was discovered in a Nevada cave in 1940, has been the subject of intense controversy since 1996, when the local Fallon Paiute-Shoshone community learned of its existence and began campaigning for its repatriation. The body was returned to the group and reburied in a private ceremony held this summer.

Another finding of note revolves around an individual who lived roughly 10,400 years ago in what is now Brazil. The skeleton revealed traces of a distinctly Australasian genetic marker unseen in any of the other samples included in the study, raising questions of how it ended up in South America. It’s possible, Meltzer tells Science’s Wade, that traces of Australasian ancestry were isolated to a small group of Siberian migrants who moved across continents without mingling amongst other populations, but additional research must be conducted before arriving at a definitive conclusion.

As Michael Greshko explains for National Geographic, the Cell study, led by Max Planck Institute geneticist Cosimo Posth, encompasses the genomes of 49 sets of ancient remains and offers evidence of two previously unidentified South American populations likely related to the main group of Southern Native Americans. One group consists of 4,200-year-old Andean residents closely linked to the Native Americans living in California’s Channel Islands, while the other connects communities that settled in Brazil and Chile around 9,000 years ago to Anzick-1, a 12,700-year-old Clovis child found in Montana.

Posth tells Gizmodo that this latter group speaks to the Clovis culture’s expansion south. He adds, however, that the Clovis-related group was soon completely replaced by an ancestral group with ties to today’s South American populations.

The final paper, published in Science Advances, sheds light on Andean peoples’ adaptation to the harsh conditions of high elevation living. Researchers led by Emory University anthropologist John Lindo drew on the genomes of seven individuals living in the region between 1,400 to 6,800 years ago, as well as dozens of DNA samples sequenced from contemporary populations. As Gizmodo reports, the team found that ancient residents of the Andean Highlands rapidly gained resistance to cold temperatures, low oxygen and UV radiation. They also learned to digest potatoes and, Greshko says, experienced stronger heart health.

Interestingly, analysis of Highland versus Lowland populations revealed vast differences in responses to European contact. Whereas the Lowlanders’ numbers dropped by 95 percent, the Highlanders only shrank by about 27 percent, likely due to adaptations in an immune gene linked with smallpox.

Overall, the studies show multiple distinct waves of migration, complicating the story of the Americas’ first inhabitants. About 16,000 years ago, descendants of the original Siberian and East Asian migrants split into the Northern and Southern Native American branches—both the Spirit Cave mummy and Anzick-1 belong to this latter group. Around 14,000 years ago, the southern branch further splintered into populations that rapidly dispersed across South America. Then, beginning 9,000 years ago, yet another wave of humans from North or Central America arrived in South America, overtaking its older populations. Finally, by at least 4,200 years ago, a group of Andean Highlanders linked to ancient Californians had spread across the Peruvian mountain range.

Jennifer Raff, an anthropological geneticist at the University of Kansas in Lawrence who was not involved in the work, tells Nature’s Ewen Callaway that the findings don’t negate centuries of previous research.

“It’s not that everything we know is getting overturned,” she says. “We’re just filling in details. We’re now moving to a much more detailed, much more accurate and richer history. That’s where the field was always going, and it’s nice to be there now.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)