View Daily Life in a Japanese-American Internment Camp Through the Lens of Ansel Adams

In 1943, one of America’s best-known photographers documented one of the best-known internment camps

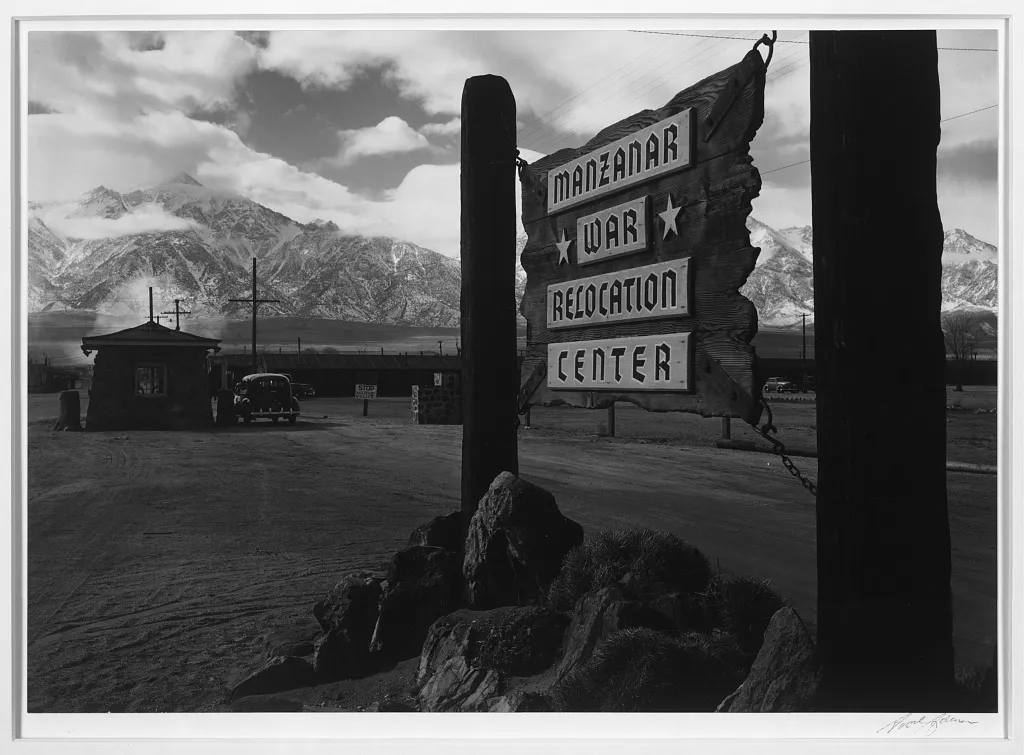

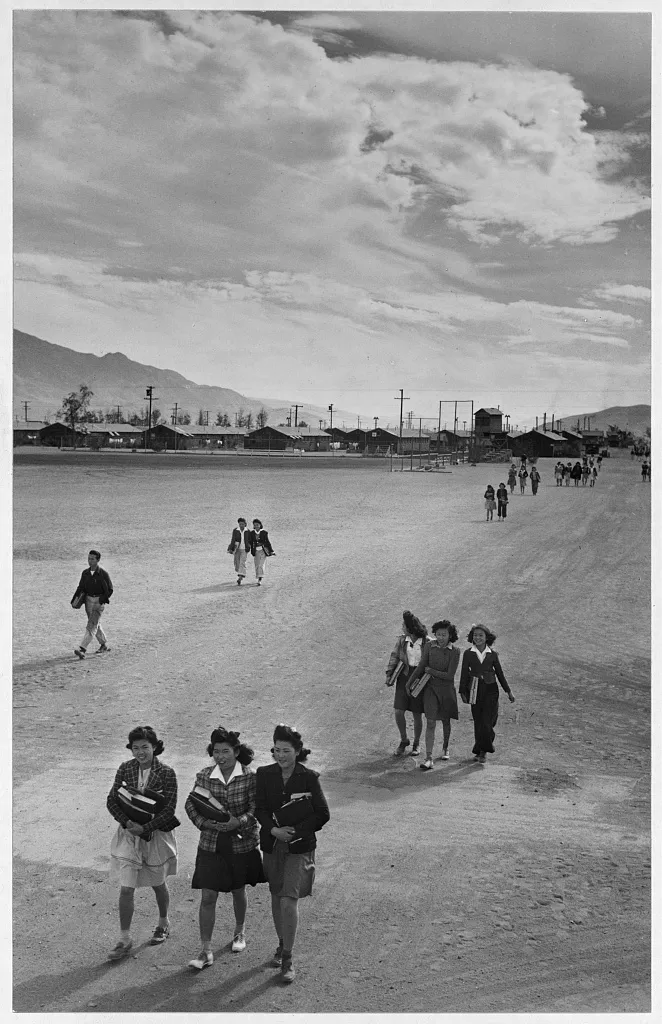

Seventy-five years ago, nearly 120,000 Americans were incarcerated because of their Japanese roots after the bombing of Pearl Harbor. More than 10,000 were forced to live in the hastily built barracks of Manzanar—two thirds of whom were American citizens by birth. Located in the middle of the high desert in California's Eastern Sierra region, Manzanar would become one of the best-known internment camps—and in 1943, one of America’s best-known photographers, Ansel Adams, documented daily life there.

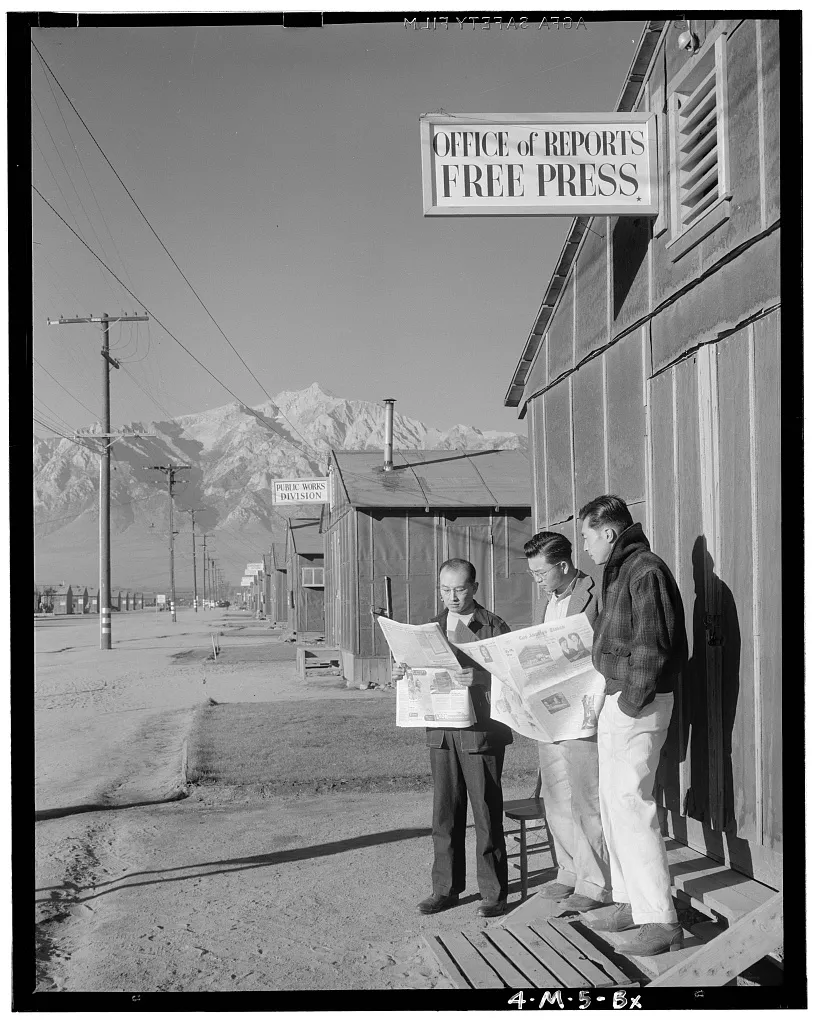

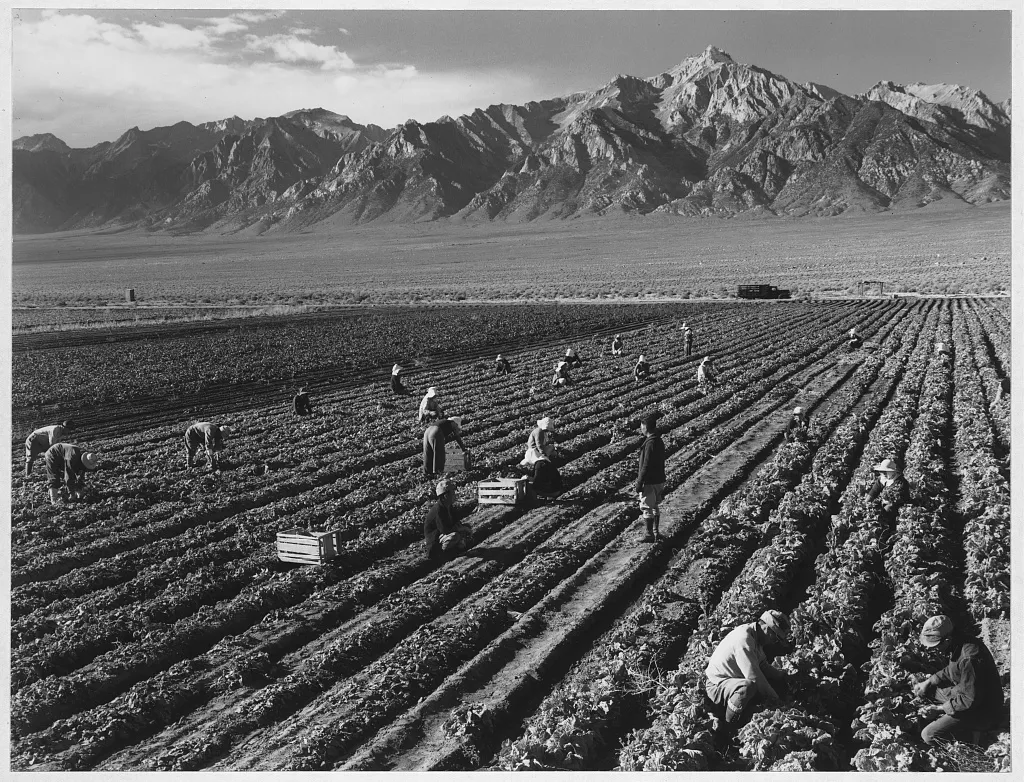

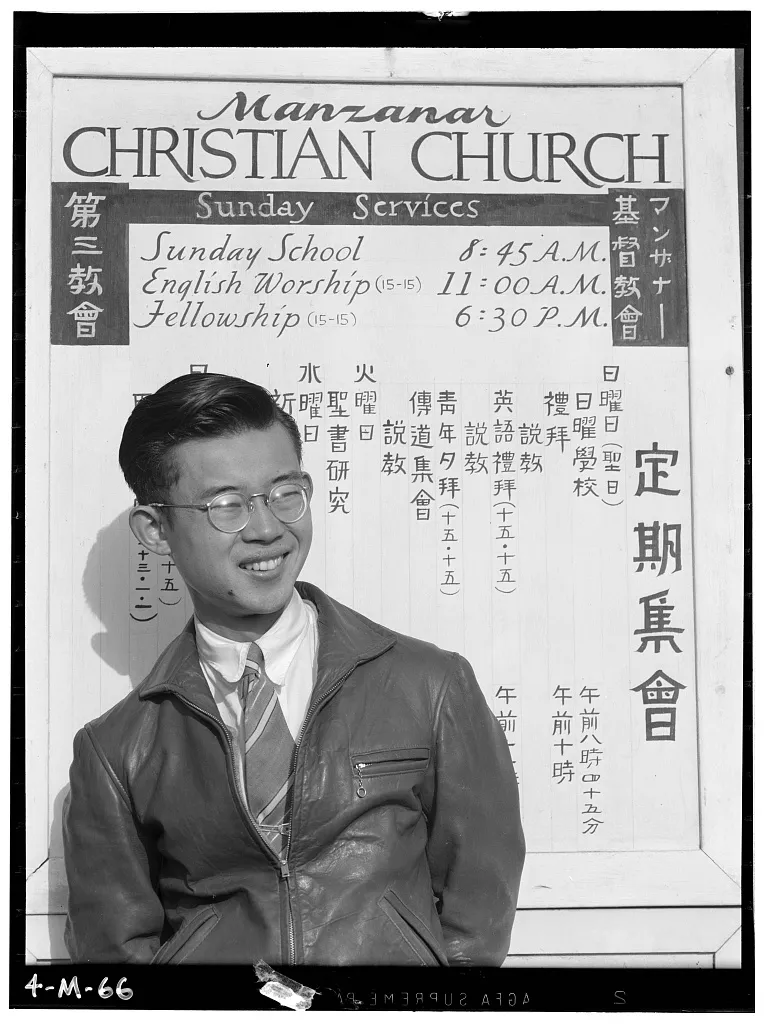

As Richard Reeves writes in his history of Japanese-American internment, Adams was friends with the camp’s director, who invited him to the camp in 1943. A “passionate man who hated the idea of the camps,” he hoped to generate sympathy for the internees by depicting the stark realities of their lives. As a result, many of his photos paint a heroic view of internees—people “born free and equal,” as the title of his book collecting the photos insists.

But his photo shoot did not go as planned. “He was frustrated…by internees’ insistence on showing only the best side of their lives behind barbed wire,” writes Reeves. Despite the smiling faces and clean barracks featured in some of Adams’ photos, though, sharp eyes can spot the spartan, uncomfortable living situation at the camp. At Manzanar, temperature extremes, dust storms and discomfort were common, and internees had to endure communal latrines and strict camp rules.

Adams wasn’t the only noteworthy photographer to train his lens on Manzanar. Dorothea Lange, whose unforgettable photos documented the Dust Bowl, photographed much of the history of Manzanar, including its construction. “Where Adams portraits seem almost heroic,” writes the NPS, Lange more often catches the semi-tragic atmosphere of her subjects.”

Though internees were initially banned from using cameras inside Manzanar, photographer Tōyō Miyatake defied the rules and photographed the camp anyway. He smuggled a lens into camp and, using a homemade camera, took about 1,500 images. He eventually became the camp’s official photographer. Though his images are not in the public domain, you can view them on his studio’s website or in various books.

The jury is still out on whether Adams’ photos are a worthy document of life at Manzanar. Do the smiling faces and busy daily lives of internees really capture their lives, or do they whitewash the truth of the camps’ isolation and injustice? “I believe Adams though of Manzanar as an assignment,” writes Brad Shirakawa in an essay for SFGate. Shirakawa, whose mother was imprisoned at another camp, is a Bay Area photographer, and he has taught photojournalism at San José State University. “He told his subjects to smile. They didn’t refuse.” The result, he says, are photos that capture the many ironies of Japanese-American internment. Click here to view them all.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erin.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erin.png)