What’s Changed in the 30 Years Since the Smithsonian Opened an Exhibition on Japanese Internment

A new display at the American History Museum marks the 75th Anniversary of Executive Order 9066

Can a museum exhibition change national policy?

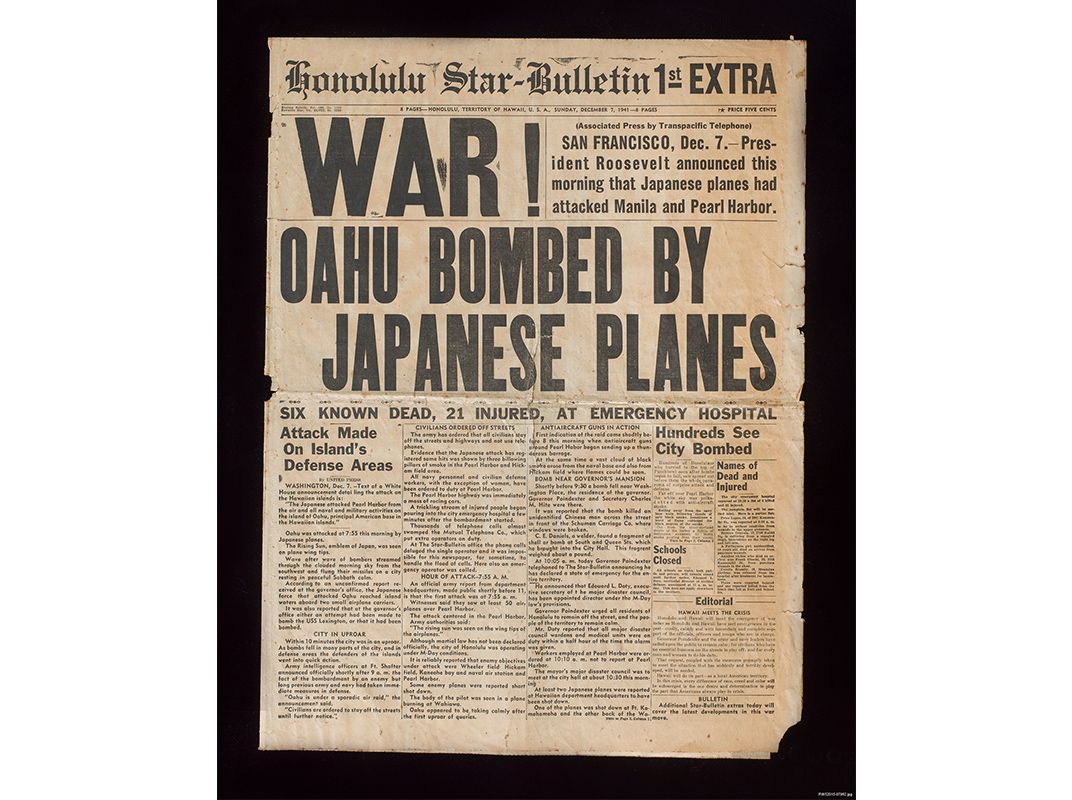

Jennifer Locke Jones, a curator at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History believes it can. When she first worked on a 1987 exhibition about the incarceration of Japanese-American citizens during World War II, President Ronald Reagan had not yet signed the bill providing restitution for survivors as a way “to right a grave wrong.”

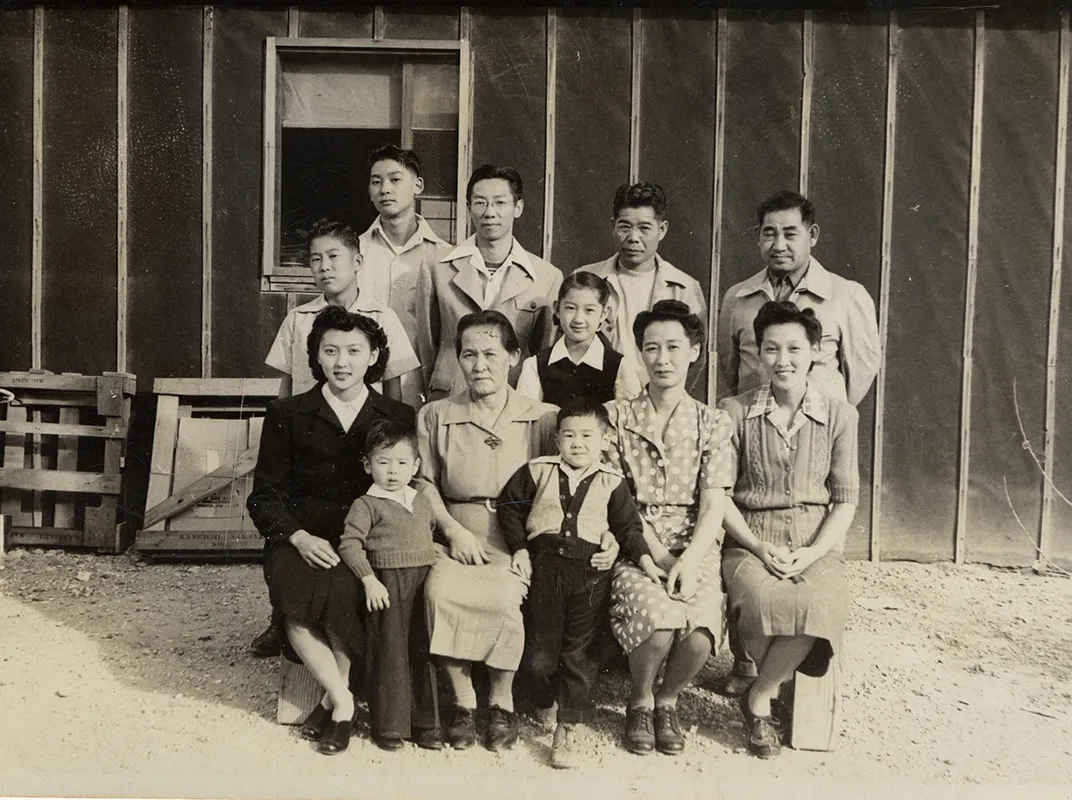

“There was no resolution,” says Jones. “There was no apology at the time.” Indeed, some visitors to the museum's exhibition “A More Perfect Union” had not been aware that 75,000 American citizens were imprisoned, along with 45,000 Japanese immigrants who were prohibited by law from becoming naturalized American citizens.

By the following year, however, Reagan would sign the bill that included a formal apology and compensation to more than 100,000 Japanese-Americans.

“One of the things that we recognize is that many members of Congress came down to see the exhibition,” Jones says. “The fact that it was here at the Smithsonian and this story was being told, there was a lot of talk at the time about it.”

The exhibition remained on view for 17 years, and during that time a memorial, the National Japanese American Memorial to Patriotism During World War II, was dedicated near the U.S. Capitol in 2000.

Now, to mark the 75th anniversary of the notorious Executive Order 9066 that called for the incarceration, the American History Museum has opened a new exhibition with help from the Teraski Family Foundation, the Japanese American Citizens League and AARP.

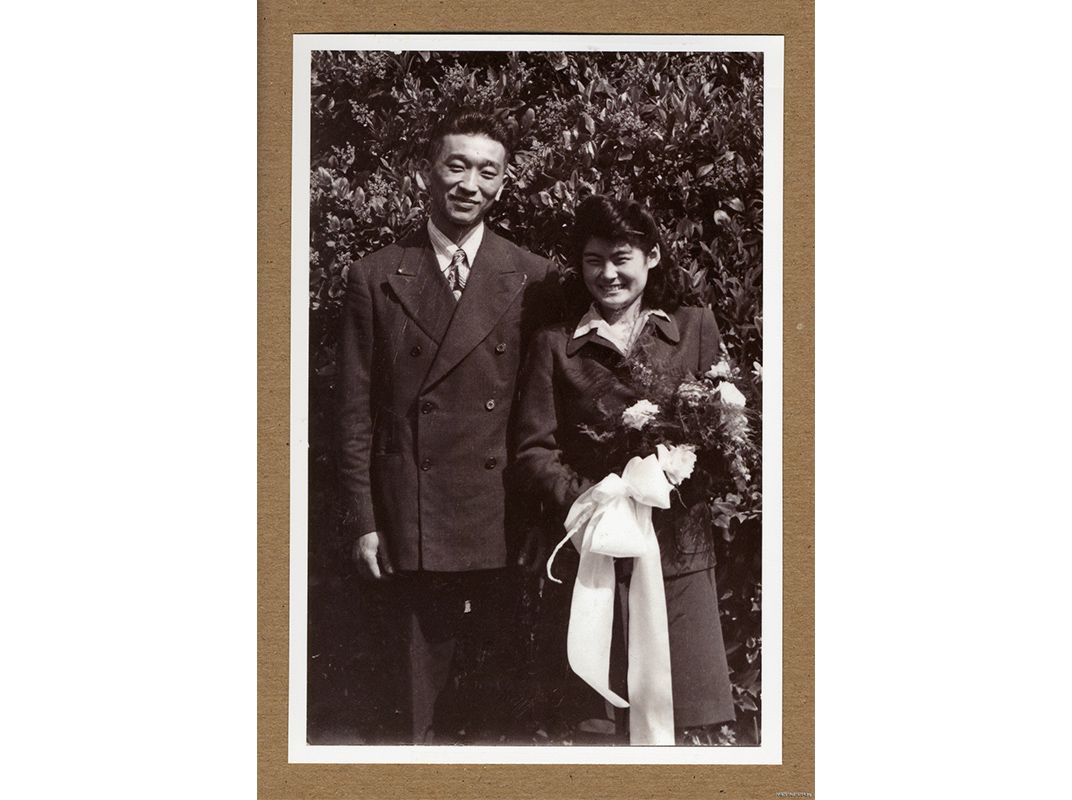

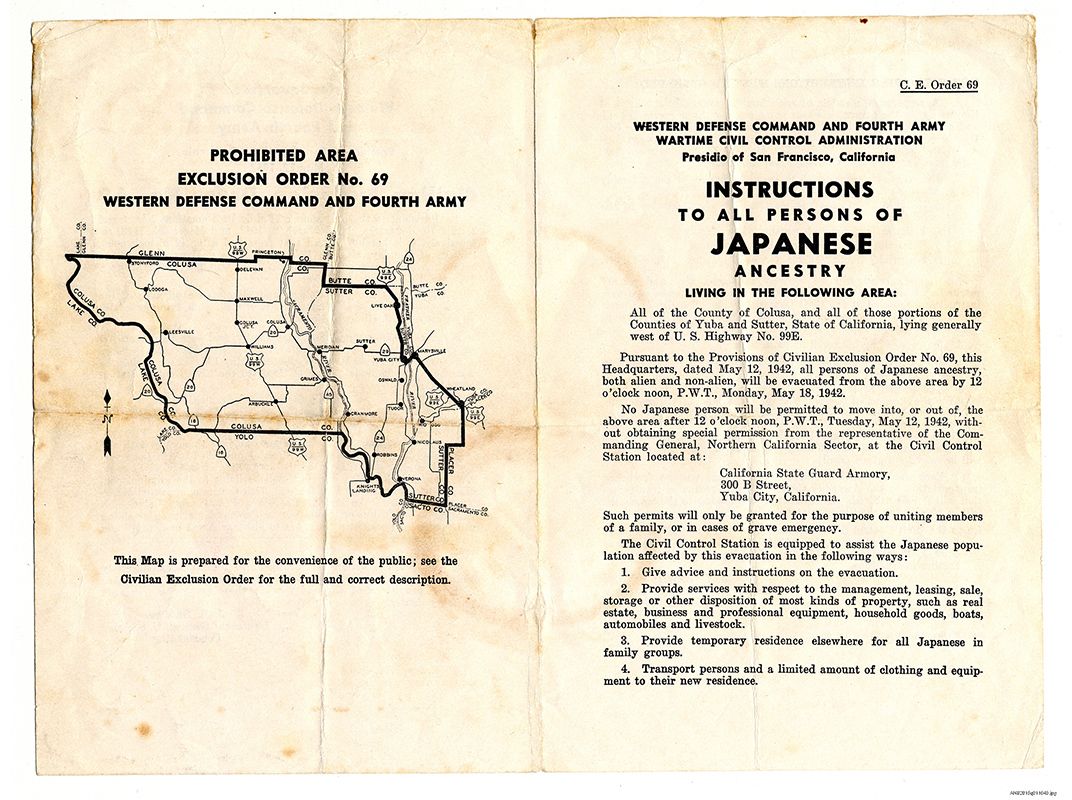

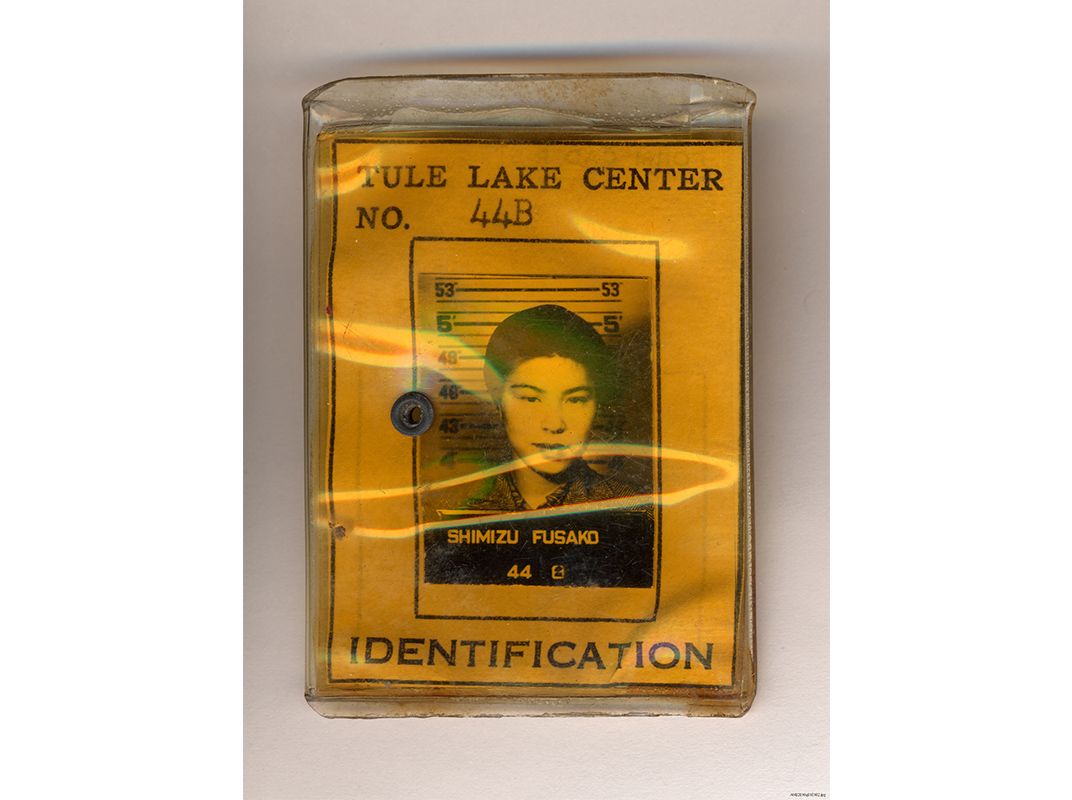

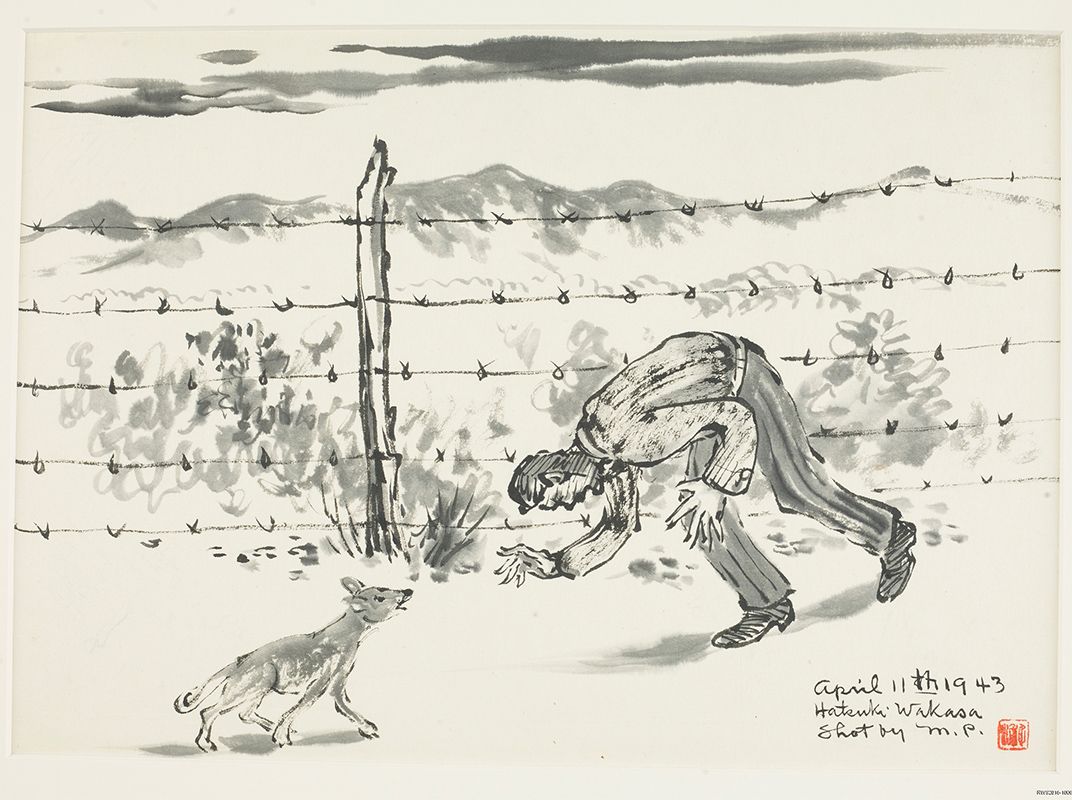

“Righting a Wrong: Japanese Americans and World War II” includes the document that President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed in February 1942, two months after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, along with a number of artifacts from the era, from the Medal of Honor awarded to Private First Class Joe M. Nishimoto of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, to fragile family mementos depicting life in the 10 large, barbed-wire enclosed camps in the West that were in operation until 1946.

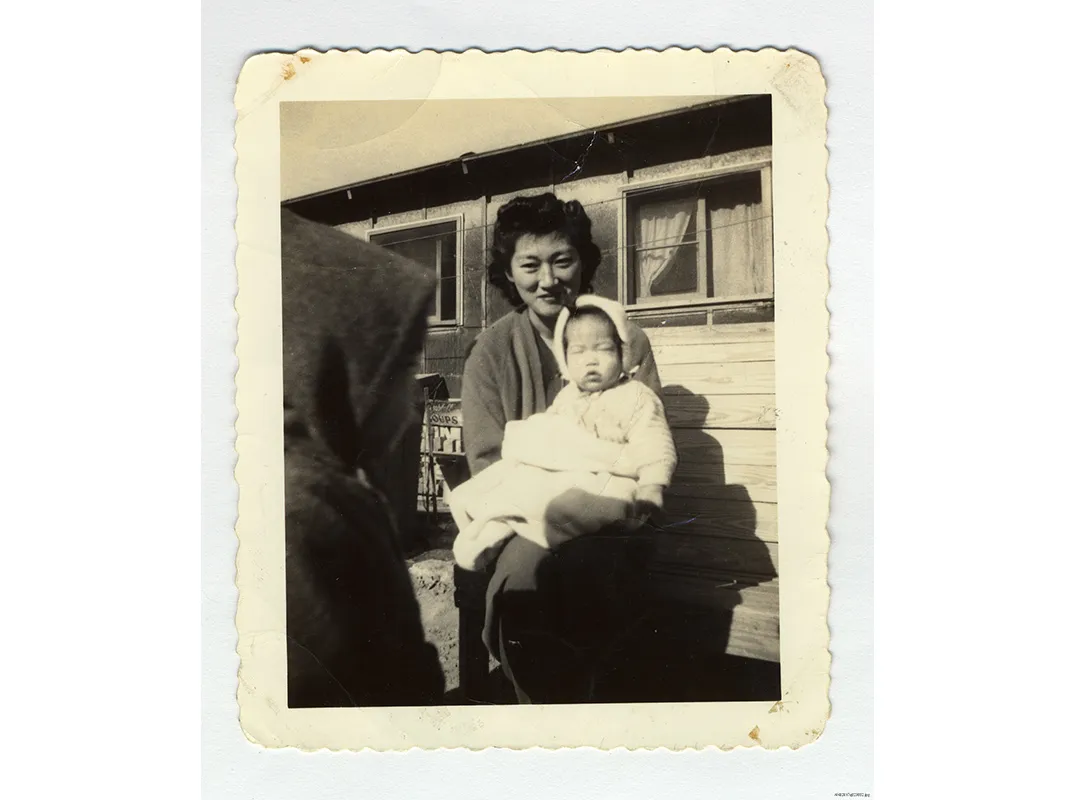

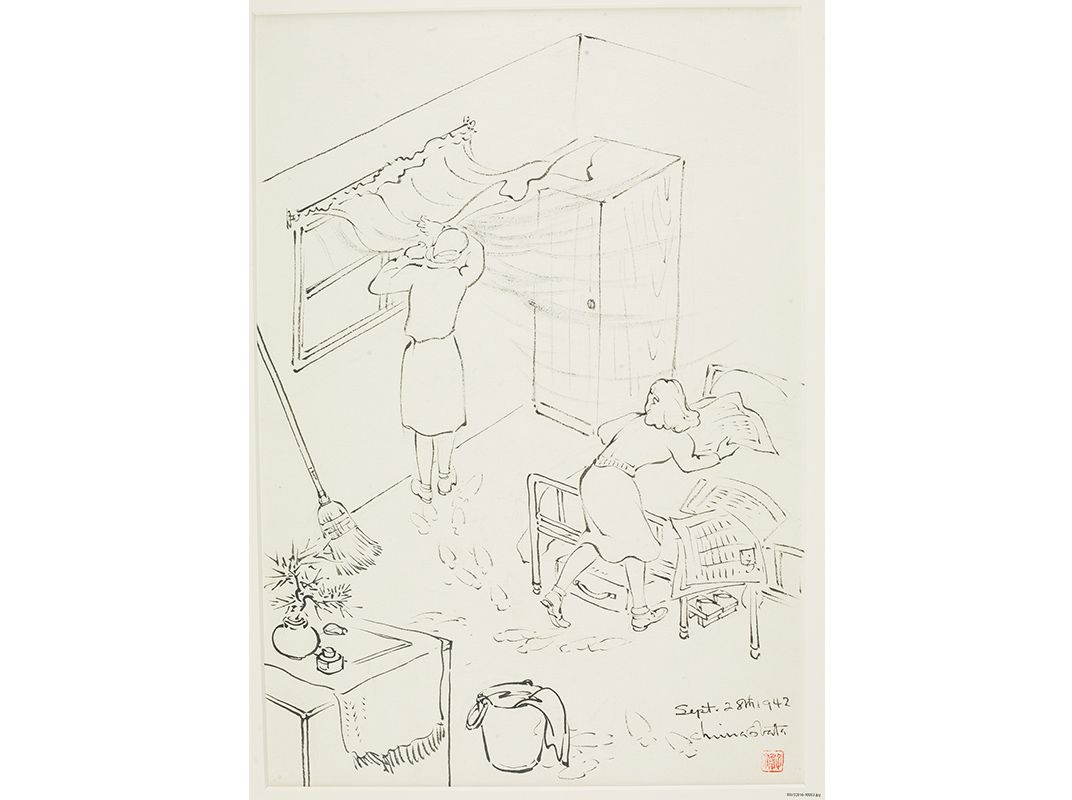

“One of the things that was really interesting when we did the first exhibition, we wanted to engage the public in the cycle of life that happened in the camps,” Jones says. “But we didn’t have the artifacts to show that cycle of life. People weren’t willing to give that up. It wasn’t something they wanted to talk about.”

In many cases, the children of those imprisoned, or those who were imprisoned as children, are now willing to donate items, she says, pointing out a particularly delicate crocheted dress for a toddler and worn by Lois Akiko Sakahara while imprisoned at Heart Mountain Relocation Center in Wyoming.

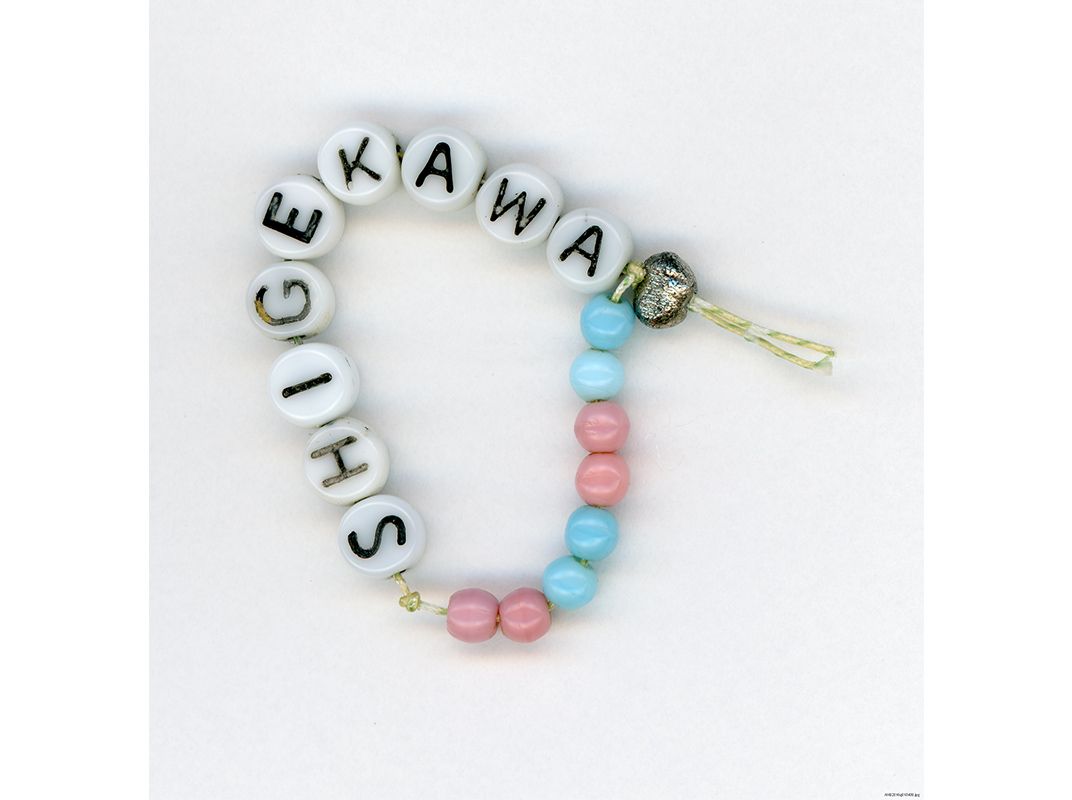

“You have a young child who is growing up in the camp she might have been 2, there’s a photograph of her and she’s wearing this dress that was crocheted in camp,” she says. “I love it. It’s fragile, and yet somebody preserved it and hung on to it. We also have a baby bracelet from a birth in the camp.”

Just as there was birth in the camps, there was death. “We were able to collect a death certificate, which we’ve never been able to collect before,” Jones says.

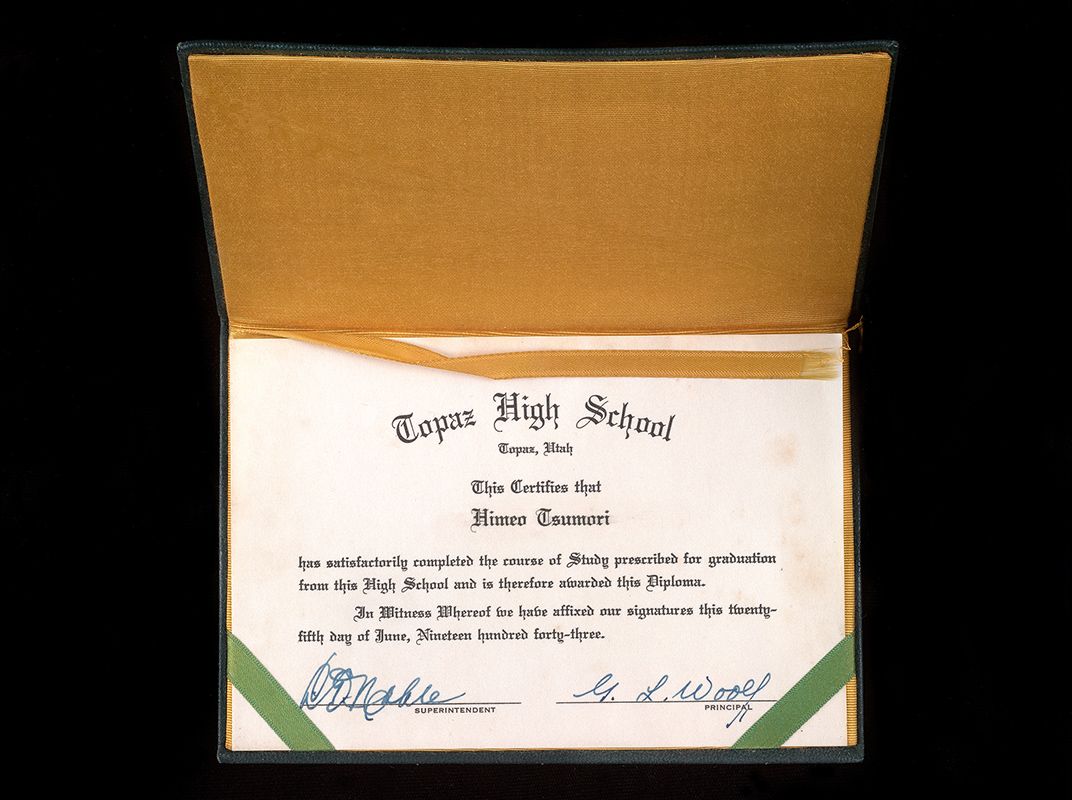

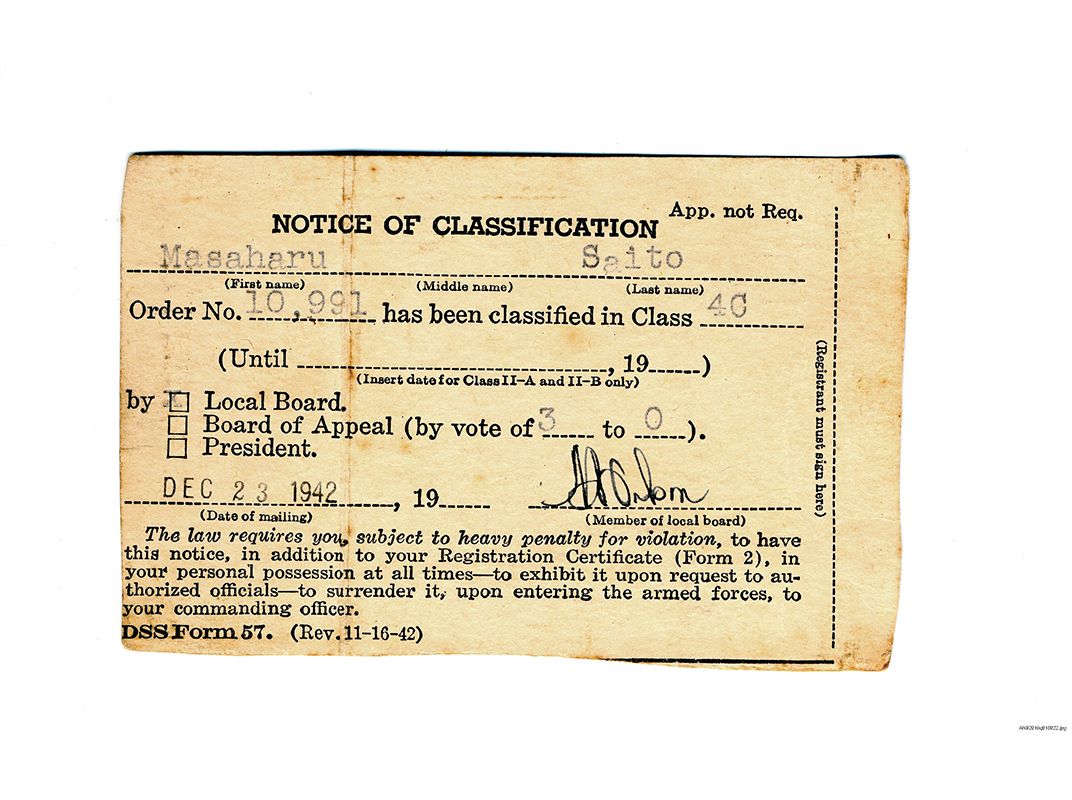

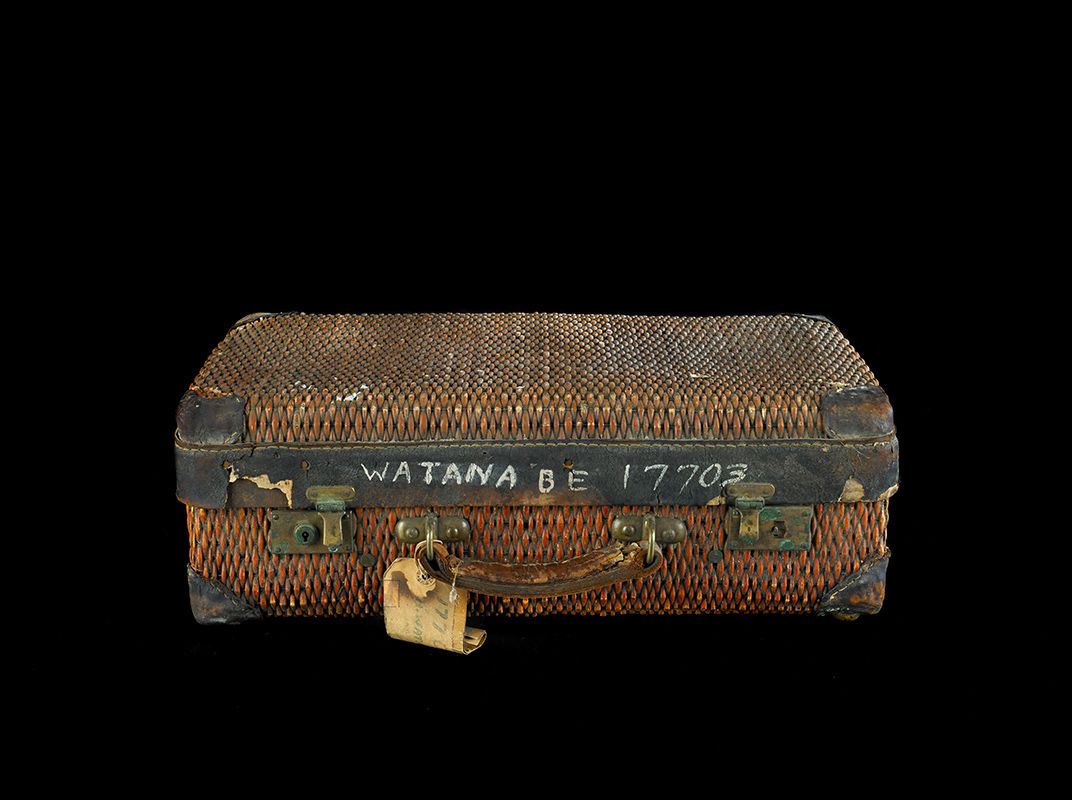

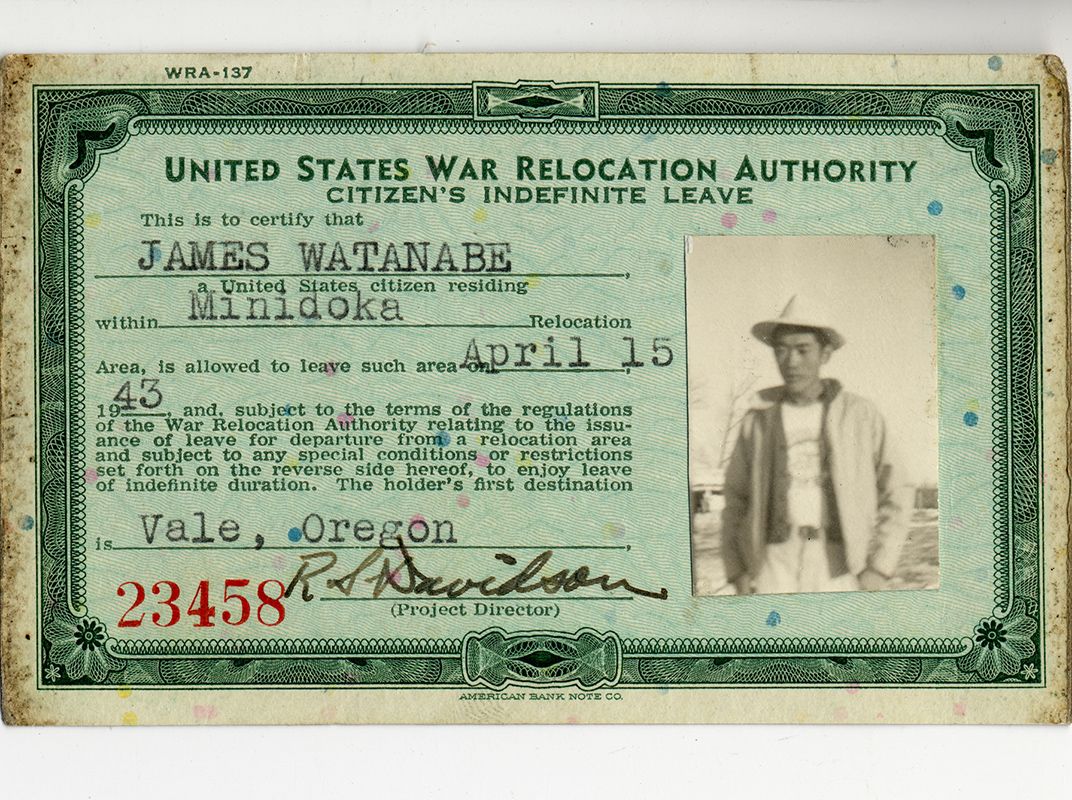

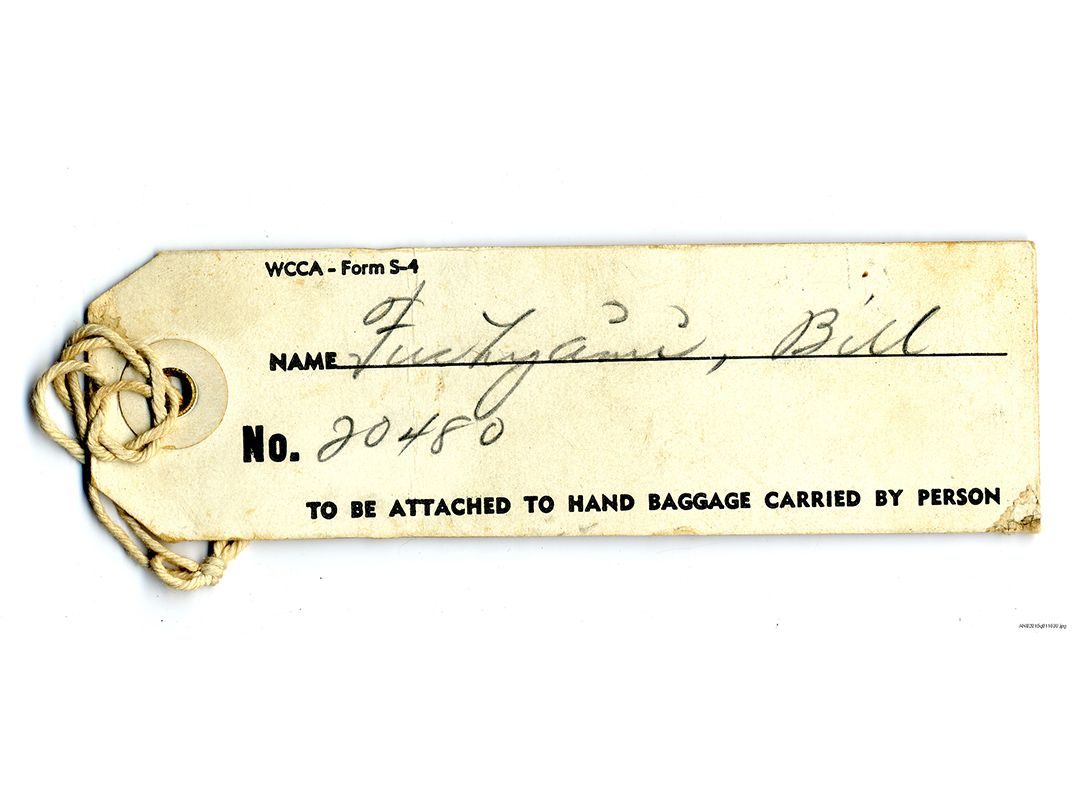

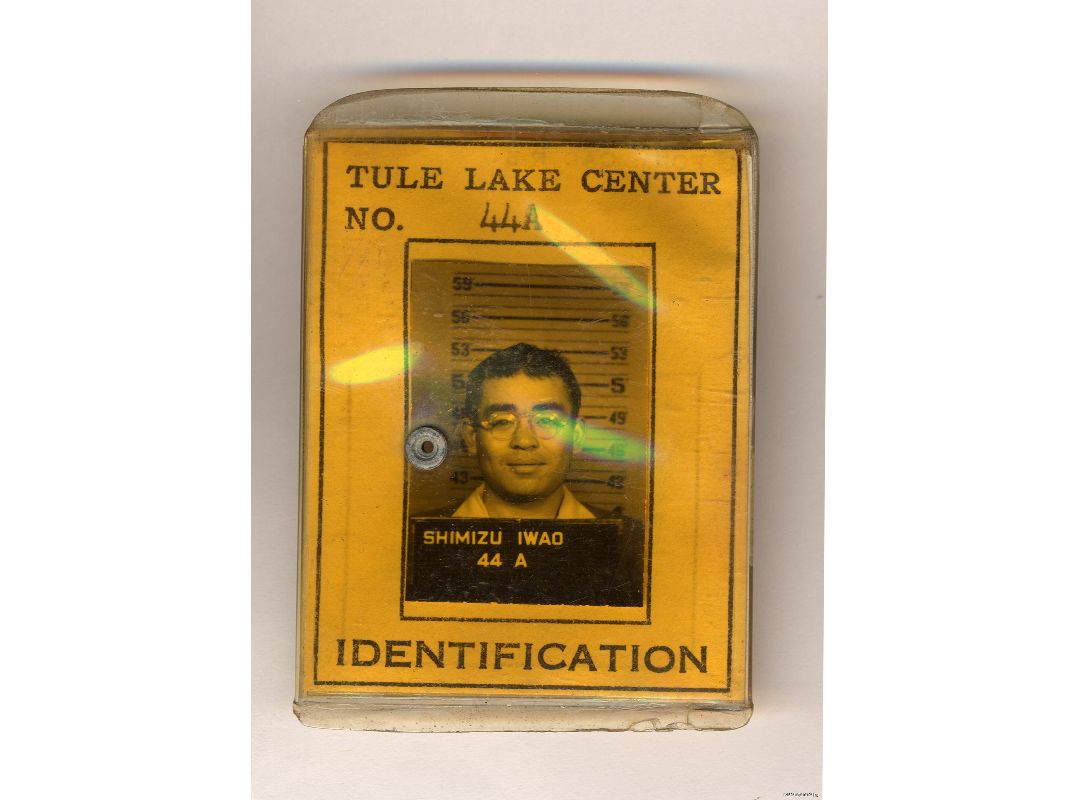

There is also a marriage certificate from a union that took place in Jerome Camp in Arkansas, an ID booklet issued by the U.S. Dept. of Justice Alien Registration,” baggage and identification tags a high school diploma from the Topa War Relocation Center in Utah and a wicker suitcase that belonged to a family, forcibly removed to the Minidoka War Relocation Center in Idaho.

Bird carvings by Sadao Oka while imprisoned in Arizona were donated by his son Seishi Oka, who at 82, was present when the exhibition opened.

“I want to emphasize though that you might get the idea that all they did in camp was sit around and carve birds, or write poetry or whatever,” he says. “But it wasn’t really like that. Because I don’t really remember my father taking that time, watching him carve and paint some birds.

“He probably did it when we were asleep. I think they did that when they had the spare time. Because he did a lot of work. They created a farm for vegetables they got to eat. They were so poor, they grew their own.”

Oka was accompanied by his sister Mitzi Oka McCullough, and both were interested in the reproduction of a 1942 editorial cartoon by Theodor Geisel, better known as Dr. Seuss.

“It’s interesting because Seuss did all those children’s books, which I had, and read to my daughter. and here he’s doing something so different,” she said. “That’s kind of stunning to me.”

She was 3 when they went into the camp; he was 5. “I am learning also because I was so young at the time,” said Oka, looking at the artifacts.

Living now in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, he’s found that fewer people were as familiar about the period of internment on the East Coast. “The information wasn’t disseminated at the time.”

“It was terrible, especially for my parents,” says Bob Fuchigami, a detainee with his family at the Granada War Relocation Center in Colorado, who was also present at the opening. “We had done nothing wrong. We did whatever the military told us to do. It was like martial law.”

Like many other families, Fuchigami, 86, says his family lost its farm in Yuma City, California, when they were relocated.

“It’s past history,” he says now. “But I’ll never forget. People say, ‘Why don’t you forget, it was a long time ago?’ I don’t forget.”

With the 1988 apology that the imprisonment was based on “race prejudice, war hysteria and a failure of political leadership” rather than military necessity, there were reparations eventually of $20,000 for survivors. But when it came, many of those who had been imprisoned had already died.

It’s something that’s never far away for Fuchigami. “You talk about what’s happening with Muslims. They’re really scared. It’s not only Muslims, it’s others. And it’s wrong,” he says. “They’re being targeted in the same way we were targeted. You look at the kind of propaganda that’s being passed around about their being dangerous. In our case, there was all this media distortion. I hate to say lies but that’s what it was. They lied.”

It leads to the original question: Could an exhibition, this exhibition, have a possible effect on national policy today?

“We hope people come in and understand American history,” Jones says. “We, as historians and as curators, want to offer people an understanding of our past so they can make sense of the present and create a more humane future for us as citizens of the United States. Through that, I’m hoping people come through here and learn about our past and learn about what executive orders can do, and how they affect people and communities.”

“Righting a Wrong: Japanese Americans and WWII” continues through Feb. 19, 2018 at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)