Arsenic and Old Tastes Made Victorian Wallpaper Deadly

Victorians were obsessed with vividly-colored wallpaper, which is on-trend for this year–though arsenic poisoning is never in style

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e1/ff/e1ffa432-ab55-41b5-b13b-c2b6dcbb89dd/pg_178-79_green.jpg)

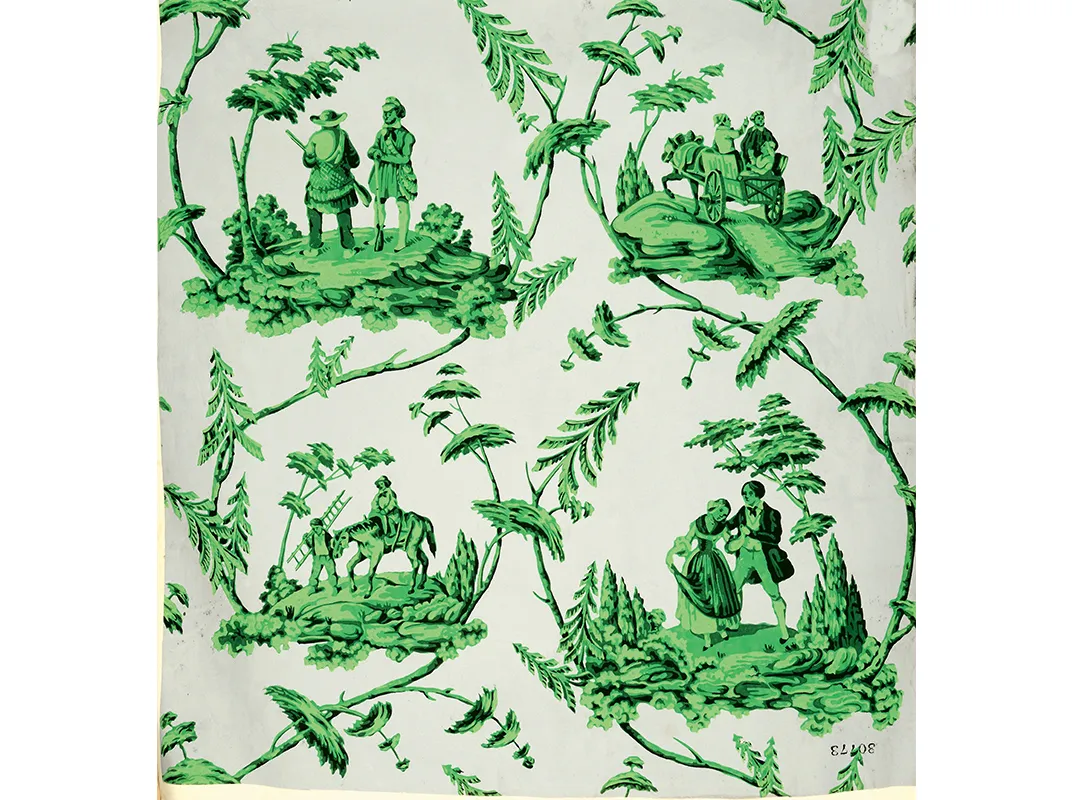

Victorian wallpaper, much like many of this year’s runway styles, was brightly colored and often full of floral designs.

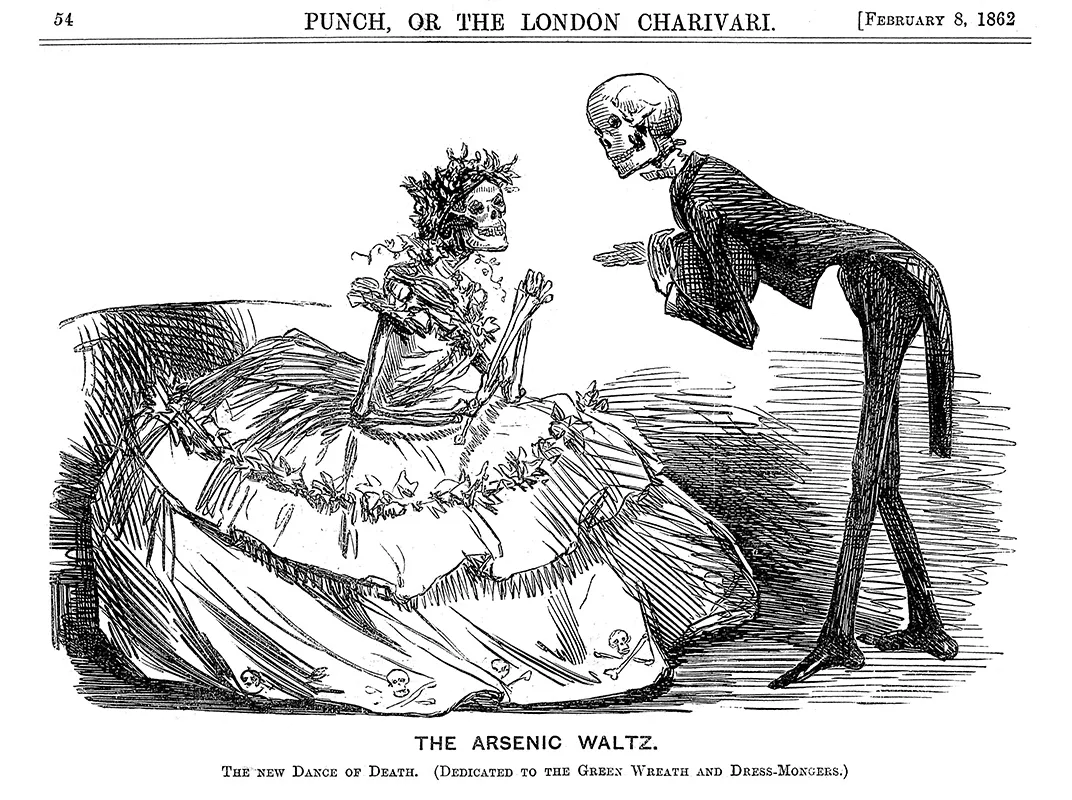

Those looks might strike you dead, but in the Victorian period, wallpaper could–and did–kill. In one sense, it wasn’t that unusual, writes Haniya Rae for The Atlantic. Arsenic was everywhere in the Victorian period, from food coloring to baby carriages. But the vivid floral wallpapers were at the center of a consumer controversy about what made something safe to have in your home.

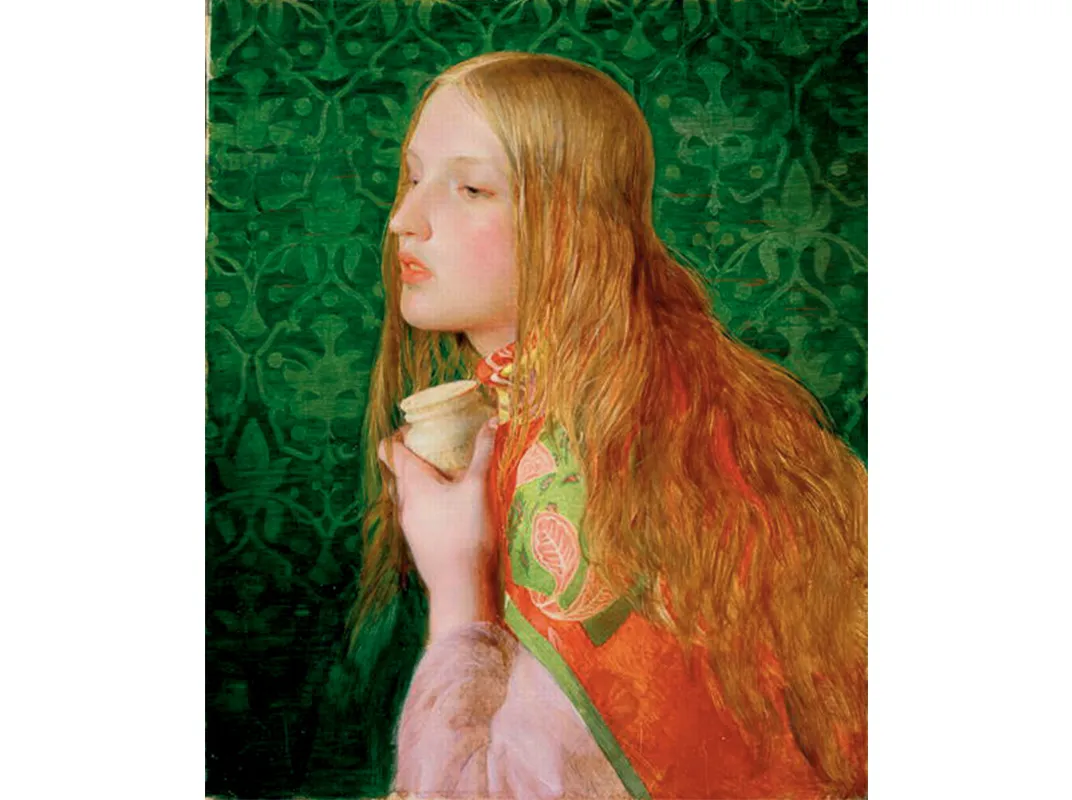

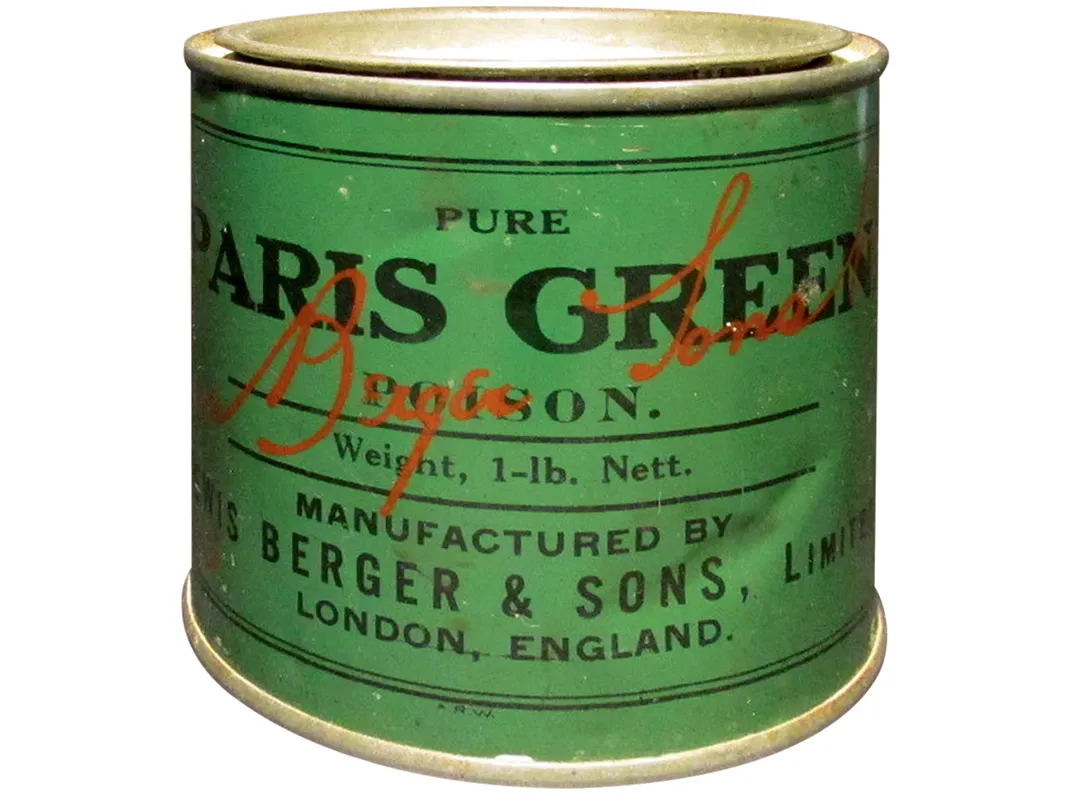

The root of the problem was the color green, writes art historian and Victorianist Lucinda Hawksley for The Telegraph. After a Swedish chemist named Carl Sheele used copper arsenite to create a bright green, “Scheele’s Green” became the in color, particularly popular with the Pre-Raphaelite movement of artists and with home decorators catering to everyone from the emerging middle class upwards. Copper arsenite, of course, contains the element arsenic.

“Before the craze for these colors had even reached Britain, the dangers associated with arsenical paints had been acknowledged in Europe, but these findings were largely ignored by British manufacturers,” she writes.

One prominent doctor named Thomas Orton nursed a family through a mysterious sickness that ultimately killed all four of their children. In desperation, one of the things he started to do was make notes about their home and its contents. He found nothing wrong with the water supply or the home’s cleanliness.

The one thing he worried about: the Turners' bedroom had green wallpaper, she writes. “For Orton, it brought to mind an unsettling theory that had been doing the rounds in certain medical circles for years: that wallpaper could kill.” This theory held that, even though nobody was eating the paper (and people did know arsenic was deadly if eaten), it could cause people to get sick and die.

Hawksley recently published a book focusing on the presence of arsenic in Victorian life. Its title, Bitten By Witch Fever, is a reference to something once said by the man at the center of all parts of this story: William Morris.

Among his many other pastimes, both professional and personal, Morris was an artist and designer associated with both the Pre-Raphaelites and the Arts and Crafts interior design movement. He was the designer of the most famous wallpaper of the nineteenth century. And he was the son of the man whose company was the largest arsenic producer in the country.

Although others suspected arsenical wallpaper, Morris didn’t believe—or claimed not to believe—that arsenic was bad for you. Morris held that because he had arsenical wallpaper in his home and his friends hadn’t caused them to get sick, so it had to be something else.

“In 1885—years after he had stopped using arsenical colors in his designs—he wrote to his friend Thomas Wardle: ’As to the arsenic scare a greater folly it is hardly possible to image: the doctors were bitten as people were bitten by the witch fever.’”

Most people didn't agree. Morris, like other wallpaper-makers, had stopped using arsenic in their papers as the result of public pressure. As newspaper reports and other media popularized the idea that arsenic was toxic, and not just when ingested, consumers turned away.