Thirty Years Later, a Gigantic Arch Is Set to Cover Chernobyl

The New Safe Confinement is one of history’s most ambitious engineering projects—and it comes not a moment too soon

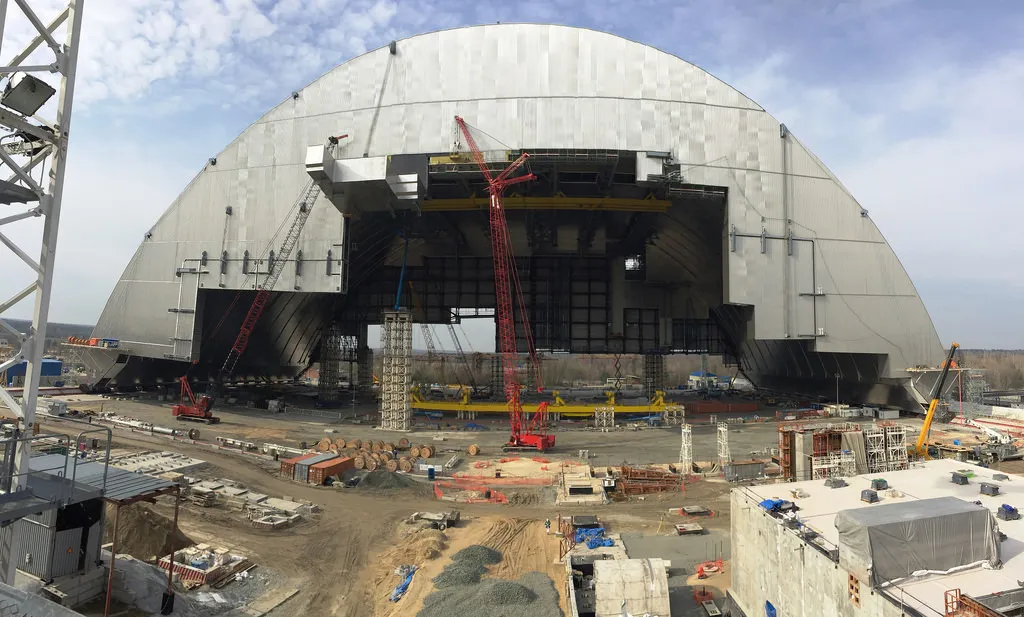

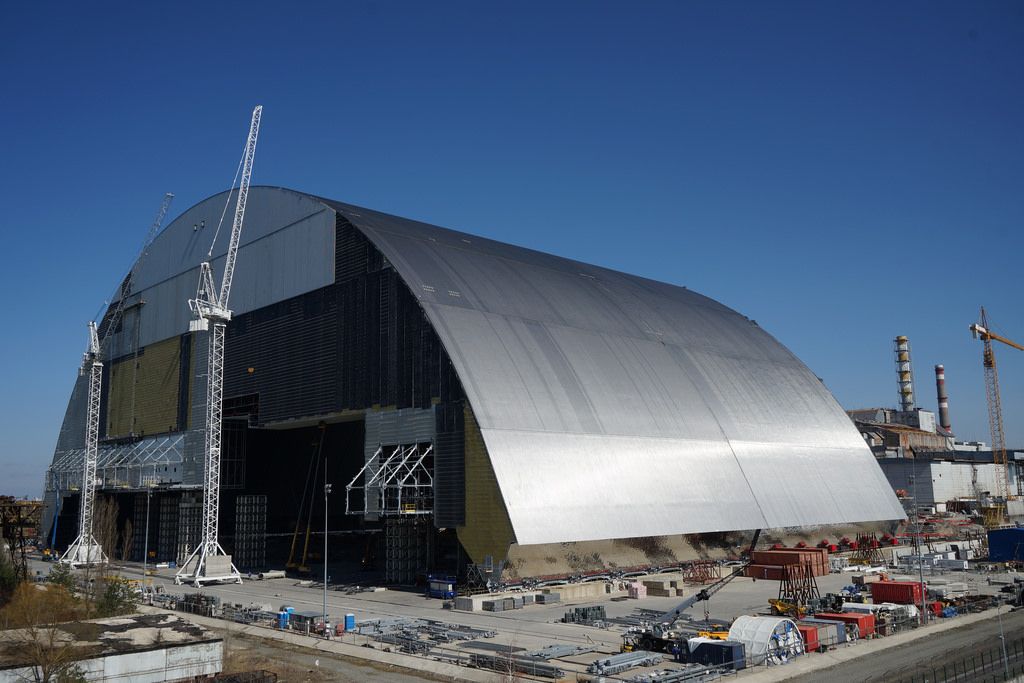

Thirty years ago, the unthinkable happened at Chernobyl when the nuclear power plant became the site of the world’s worst nuclear disaster. To contain the Level 7 radiation spewing from the plant, the reactor was enclosed in a concrete sarcophagus built in haste by workers who risked their lives to save others. Now, reports National Geographic’s John Wendle, the crumbling tomb is being replaced by a giant stainless steel arch.

The structure is called the New Safe Confinement, and it’s one of the most ambitious engineering projects ever undertaken. Since 2010, workers have been building a massive arch that will slide over the entire existing sarcophagus to contain its radiation over a 100-year period. Tall enough to contain structures like St. Paul’s in London or Notre Dame in Paris, the arch will be nearly 361 feet high and weigh more than 30,000 tons. Ironically, its size and iconic architecture will likely make it a landmark of sorts—one with grim connotations.

The NSC has been in the works since the Ukrainian government hosted a design competition in 1992, and its estimated completion date of 2017 won’t be a moment too soon. Wendle tells the story of how Ilya Suslov, a construction foreman who volunteered to clean up the site, helped build the temporary, now-crumbling concrete structure in a matter of just eight months. It began to crack soon after, and in recent years even more worries surfaced about its integrity, especially in the face of roof collapses at other parts of the facility.

Plagued by delays and funding crises, the NSC represents what could be humanity’s only chance to rein in further damage from Chernobyl. The exclusion zone that surrounds the site is already a strange testament to the power of nuclear radiation—milk tested just outside the zone, for example, contains ten times the concentration of radioactive isotopes than is permissible in Belarus. If the concrete tomb truly fails, the tons of uranium, plutonium, and boron inside could resurrect the power plant’s risk. Not that building the arch itself is without risks: Workers who slide the 853-foot-wide, 541-foot-long structure over the existing concrete structure will do so over the course of 33 hours of radioactive exposure.

That risk seems minuscule compared with the fates faced by the nearly one million “liquidators” who were forced to build the original sarcophagus by the Soviet government. Many of those workers died or face ongoing health consequences—and have had a hard time receiving public acknowledgment or compensation for their injuries. The cost of the NSC—about three billion dollars—pales in comparison to what the disaster has already cost the people who braved the unthinkable so that others might live.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erin.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erin.png)