These Early Infographics Illustrated the Plight of America’s Poor

Florence Kelley used hard numbers to effect change

When labor reformer Florence Kelley arrived at Chicago’s Hull House in 1891, she had nowhere else to go. On the run from an abusive husband in New York and in fear of losing her children, she needed a place to live and some gainful employment. She found it in America’s most famous settlement house. Kelley eventually became one of the best-known Progressive-era reformers and the first woman to hold statewide office in Illinois. But the labor rights activist, who was born 157 years ago today, accomplished another amazing feat at Hull House: a set of early infographics that brought the plight of America’s poor to life.

Kelley was already an accomplished activist by the time she arrived at Hull House. Then known as Florence Wischnewetzky, once she got to Illinois, she assumed her maiden name and began divorce proceedings (at the time, women were not able to get divorces for their husbands’ failure to support them in New York). There was plenty to do at Hull House: the settlement house already served thousands of poor people per week, offering food, classes, an employment bureau, day care and libraries to those living in Chicago’s Nineteenth Ward slums.

Hull House became known as a kind of testing ground for brilliant, reform-minded women. But its founder, Jane Addams, knew it was not enough to merely serve the poor. To be of maximum benefit to the estimated 40 percent of Chicago’s population who were immigrants, the women of Hull House needed to document the conditions that surrounded them. They may not have seen it that way, but the workers of Hull House were laying the foundations for modern social work.

Social work starts with data, and Kelley was assigned the task of compiling statistical information about Chicago’s poor communities. She was soon hired by the United States Bureau of Labor Statistics, which was working to lay the foundation for stricter labor laws. With the help of other Hull House workers and the Bureau, Kelley entered tenements, inspected sweatshops and poked into the lives of thousands of Chicago immigrants living in squalid and unsustainable conditions. The work was tedious, but Kelley saw how it could lead to social change.

Part of Kelley’s job was to expose Chicago’s “sweating-system”—filthy, overcrowded factories where workers toiled long hours with no labor protections. At the time, factories not only employed small children and farmed out work to tenement homes, but paid workers a pittance for their labor. Kelley described sweatshops located in basements, stables and sheds that were riddled with disease and lacking basic amenities.

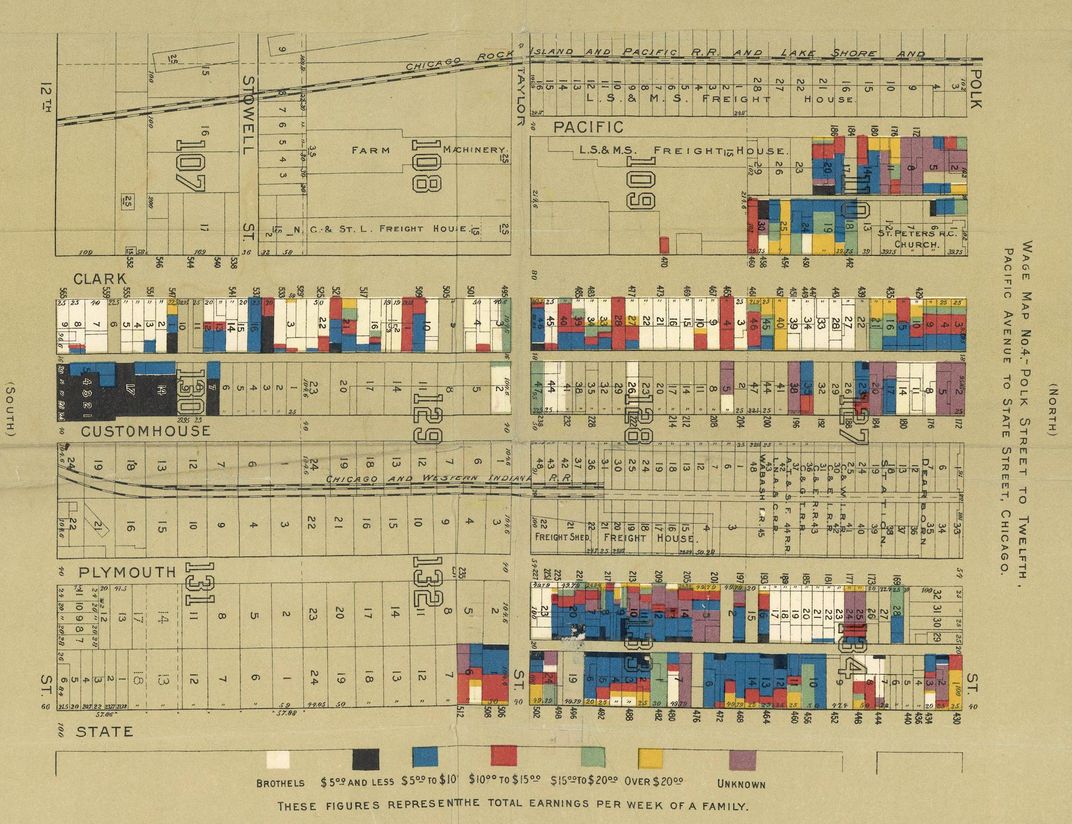

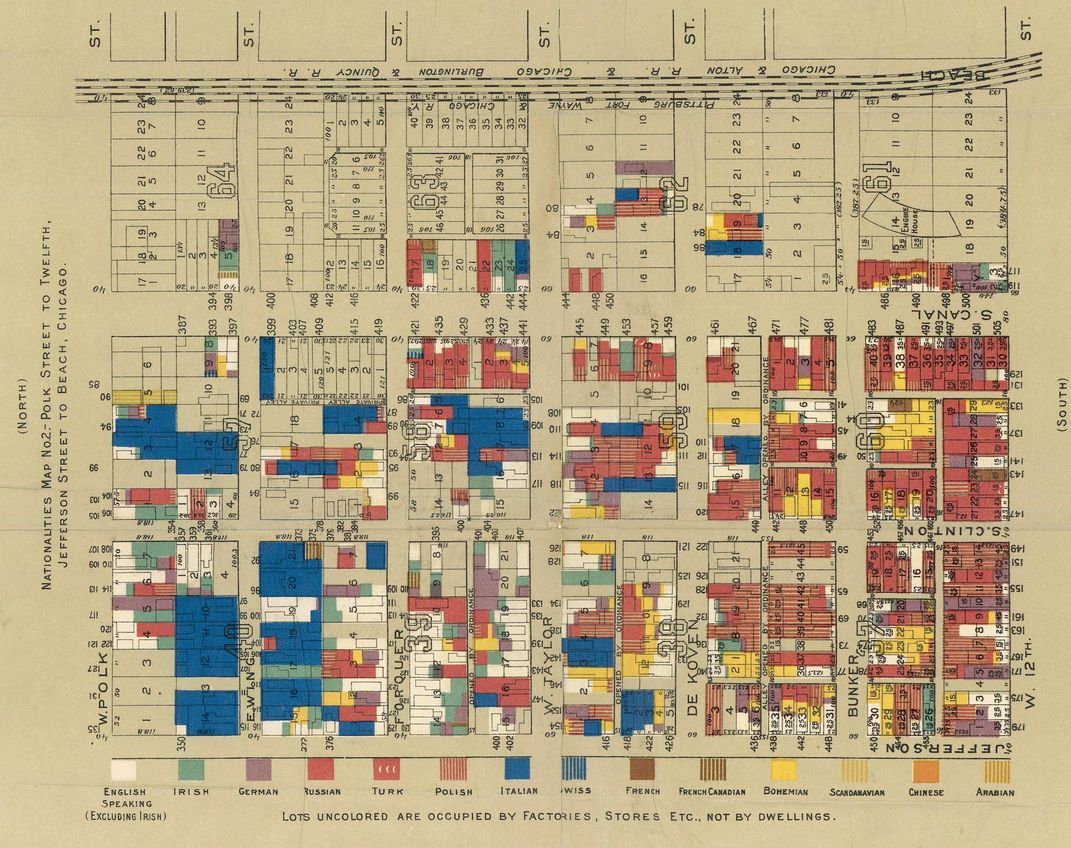

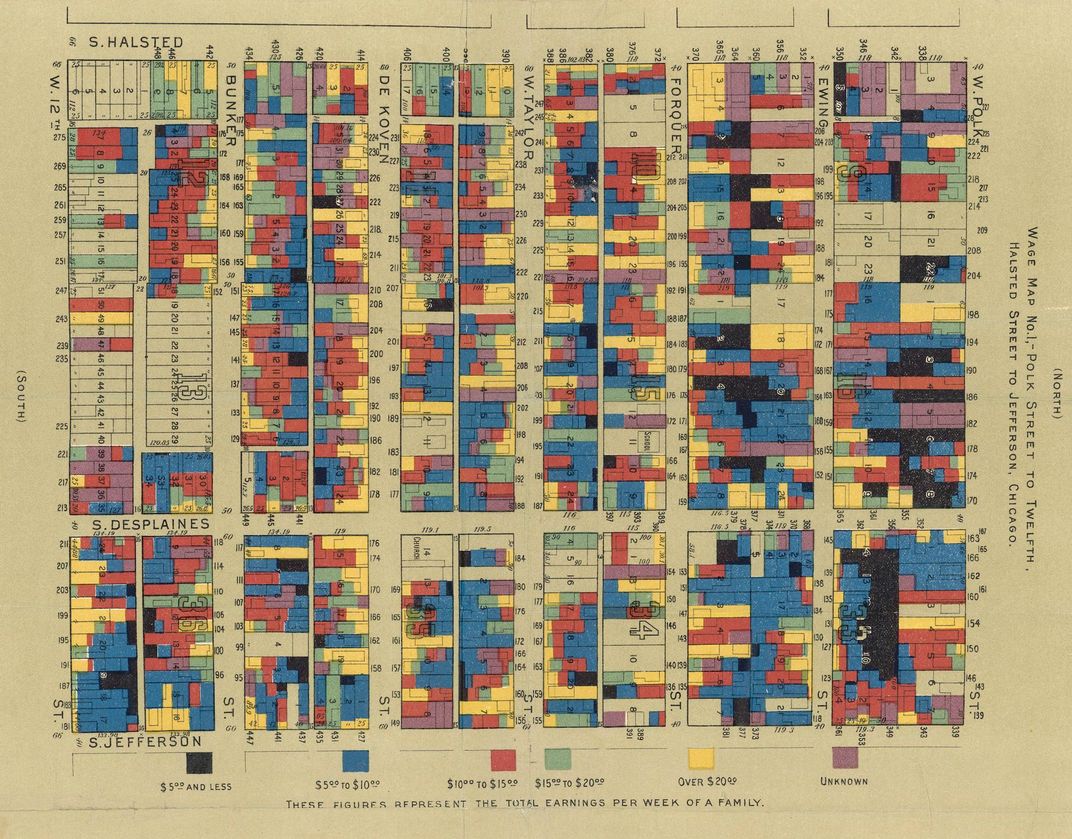

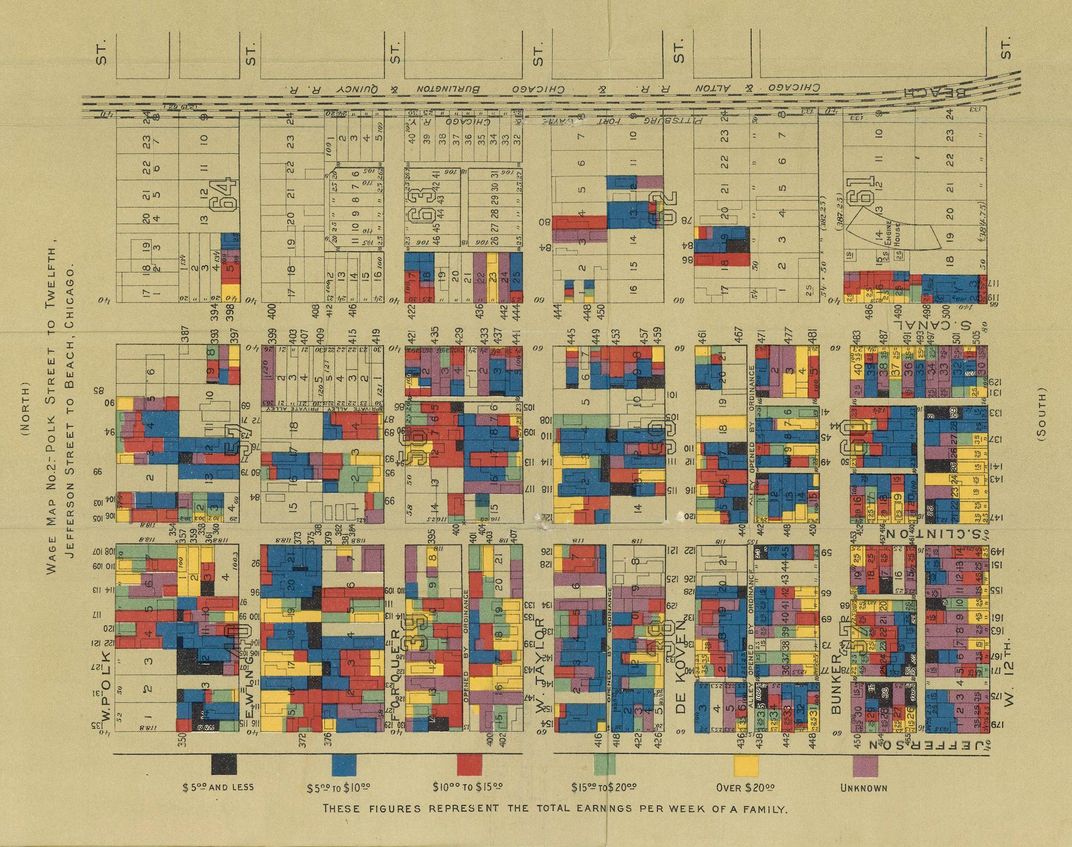

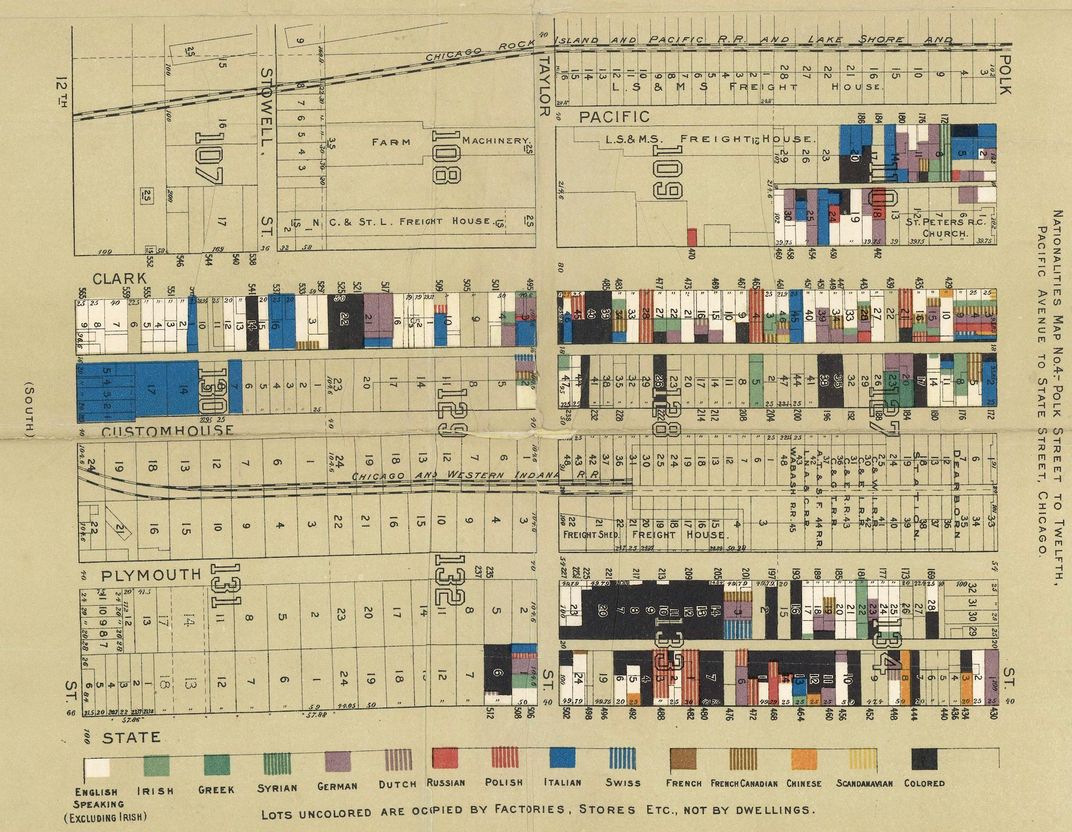

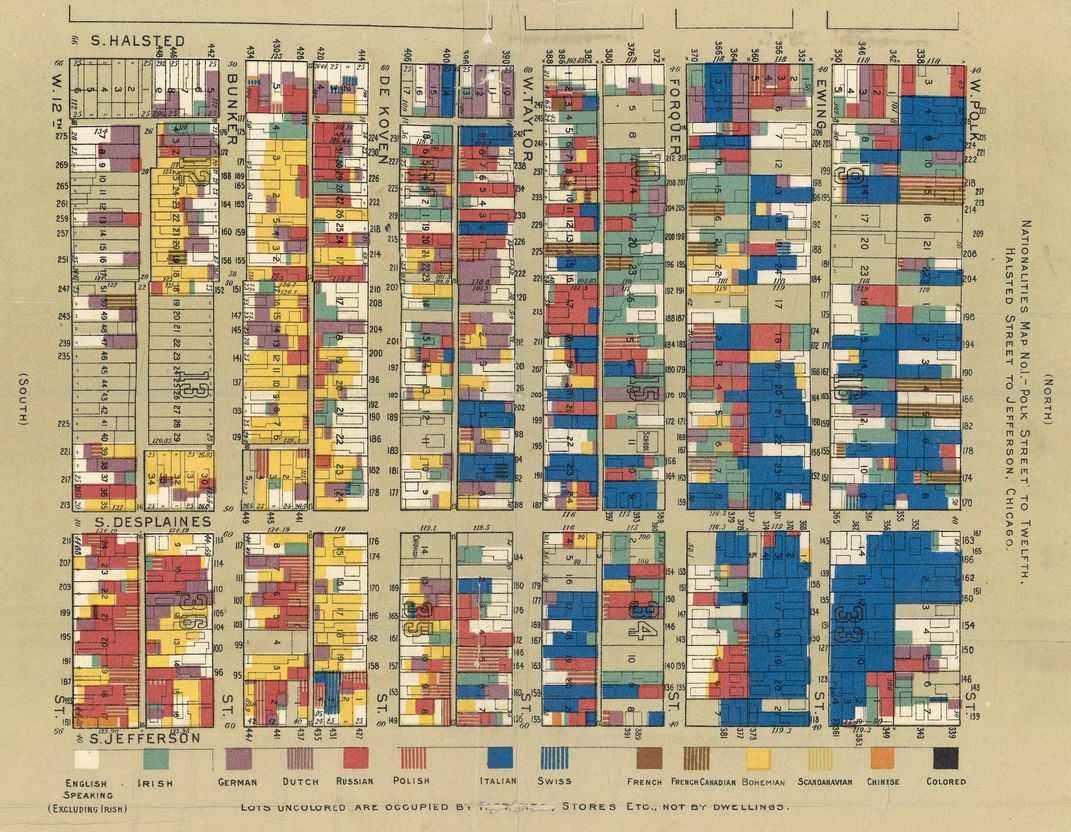

To illustrate the conditions Addams and her colleagues uncovered, they turned to the work of Charles Booth, a social reformer who helped expose conditions of poverty in England. Booth was known for his colorful, infographic-like charts that brought data to life. Inspired by his work, the workers at Hull House created Hull House Maps and Papers, an 1895 book filled with classic maps on the conditions in which Chicago’s poor labored and lived.

The maps revealed the wage conditions of Chicago immigrant and poor families—some of whom earned less than $5 a week (roughly $125 in today's dollars), where they were concentrated and what their nationalities were. The demographics revealed, for example, how poor black residents were shunted off to dwellings near railroad tracks, and the diversity and poverty of the neighborhoods that surrounded Hull House.

Kelley’s work at Hull House changed lives. Not only did Kelley herself get hired as the nation’s first female factory inspector and go on to a vaunted career in social reform, but her maps led the way for labor reform and social work to be seen as a discipline. Her work went on to be used as part of a national report on slum conditions commissioned by Congress, and that data was then used to support the stricter labor laws of the early 20th century. The echoes of Kelley’s infographics can be felt in academia and labor laws to this day—a reminder that it’s as important to see statistics as it is to read them.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erin.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erin.png)