Stephen Sondheim’s Lost College Musical Was Found Hidden in Plain Sight

Live recordings from “Phinney’s Rainbow” had been sitting on a journalist’s bookshelf for years

:focal(2506x1933:2507x1934)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/52/66/526633ed-7fd9-4860-ac52-6e250459c369/gettyimages-103429928.jpg)

While reorganizing his office recently, journalist Paul Salsini noticed a gap on a shelf. A CD had become dislodged. At some unknown juncture, he tells NPR’s Bob Mondello, it “literally fell through the cracks—and fell into the next shelf below.”

Salsini picked up the CD and played it. Immediately, he knew what he was listening to: Phinney’s Rainbow, one of Stephen Sondheim’s first musicals. Recordings of the full 19 tracks, clocking in at an hour and 20 minutes, had never been previously published (as far as anyone knew).

Experts assumed they were simply lost to time—which is perhaps what their composer, who died in November 2021 at age 91, would have wanted.

“He [did] not like his juvenilia recovered and made public, so I don’t think he would like this out there,” Salsini tells Mark Kennedy of the Associated Press (AP). “But that’s not my concern. I’m a journalist, and this is news.”

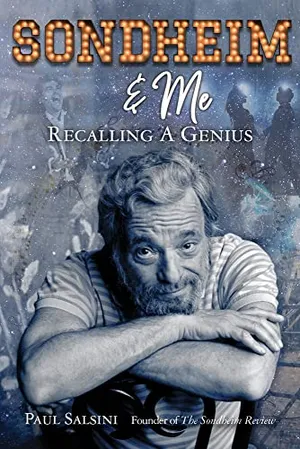

Salsini has spent many years steeped in all things Sondheim. In 1994, he founded a quarterly magazine titled the Sondheim Review, and earlier this year, he published Sondheim & Me: Revealing a Musical Genius, a book about his relationship with the musical theater icon.

Sondheim & Me: Revealing a Musical Genius

A memoir chronicling the relationship between American musical composer Stephen Sondheim and journalist Paul Salsini during the latter's time as the founder and editor of The Sondheim Review, the only publication devoted solely to Sondheim's work during his lifetime.

When Sondheim wrote the music for Phinney’s Rainbow in 1948, he was an 18-year-old sophomore at Williams College in Massachusetts. He co-wrote the book and lyrics with Josiah T.S. Horton, another student. The school’s drama society, Cap and Bells, held four performances with a cast of 52 students.

The title is a reference to both Finian’s Rainbow, a Broadway musical that debuted in 1947, and James Phinney Baxter III, Williams’ then-president. The show is a satire of college life at Swindlehurst Prep, a fictionalized stand-in for Williams.

Sheet music for the production was published in 1948, but only a select few recordings had been publicly available before now. The overture and a song called “How Do I Know?” are included in various anthologies and albums.

Other than that, writes NPR, Phinney’s Rainbow is “the stuff of legend in theater circles because nobody’s heard much of it.”

Born in 1930, Sondheim is one of musical theater’s legends. In his 20s, he wrote the lyrics for West Side Story (1957) and Gypsy (1959). Later in his career, he wrote both the music and lyrics for most of his big hits, including A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum (1962), Company (1970), Follies (1971), Sweeney Todd (1979), Sunday in the Park With George (1984) and Into the Woods (1987).

But before all these came Phinney’s Rainbow, a production even Sondheim scholars aren’t too familiar with.

“As somebody who’s lived and breathed Sondheim to the degree I’ve been able to for my entire adult life, this is a score I really don’t know,” Mark Eden Horowitz, a senior music specialist at the Library of Congress, tells NPR.

In the recordings, Sondheim explores themes he would be drawn to for the duration of his career. In particular, Salsini tells the AP, the song “How Do I Know?” is “a precursor for so many of Sondheim’s songs in which he expresses a longing, a longing for love, a longing for affection”:

And I asked you when

And you said I would know!

But how will I know

When I know that you said ‘no’?

I just don’t know!

Salsini plans to donate his copy of the CD to the Sondheim Research Collection in Milwaukee, where it will be available for public listening. More copies may be floating around, too. After learning of the CD’s existence, Horowitz was able to track down a second copy in just a few hours.

“Sondheim’s ‘juvenilia’ in this case hasn’t so much been missing, as hiding in plain sight,” notes NPR.

Perhaps Sondheim wouldn’t mind his juvenilia resurfacing, says Horowitz. The composer wasn’t particularly concerned with what happened after his death. As he once said, “I’m one of those people [who] doesn’t care about posterity.”

Besides, adds Horowitz, “He thought it was valuable for people to see early work and mediocre work and realize that even one’s heroes grew over time.”

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/ellen_wexler.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/ellen_wexler.png)