Antikythera Shipwreck Yields New Cache of Treasures, Hints More May Be Buried at Site

The discovery of an ancient bronze arm is a rare archaeological find

While sailing from Asia Minor to Rome in around 60 B.C., a hulking ship went down off the coast of Antikythera, a small Greek island located between Crete and the Peloponnese. Since it was discovered by sponge divers in 1900, the Antikythera shipwreck has yielded a trove of ancient artifacts, and a recent expedition suggests there are still more treasures to be found. As Ian Sample reports for the Guardian, marine archaeologists have unearthed an arm made of bronze at the site, and they believe at least seven rare bronze statues may lie buried there.

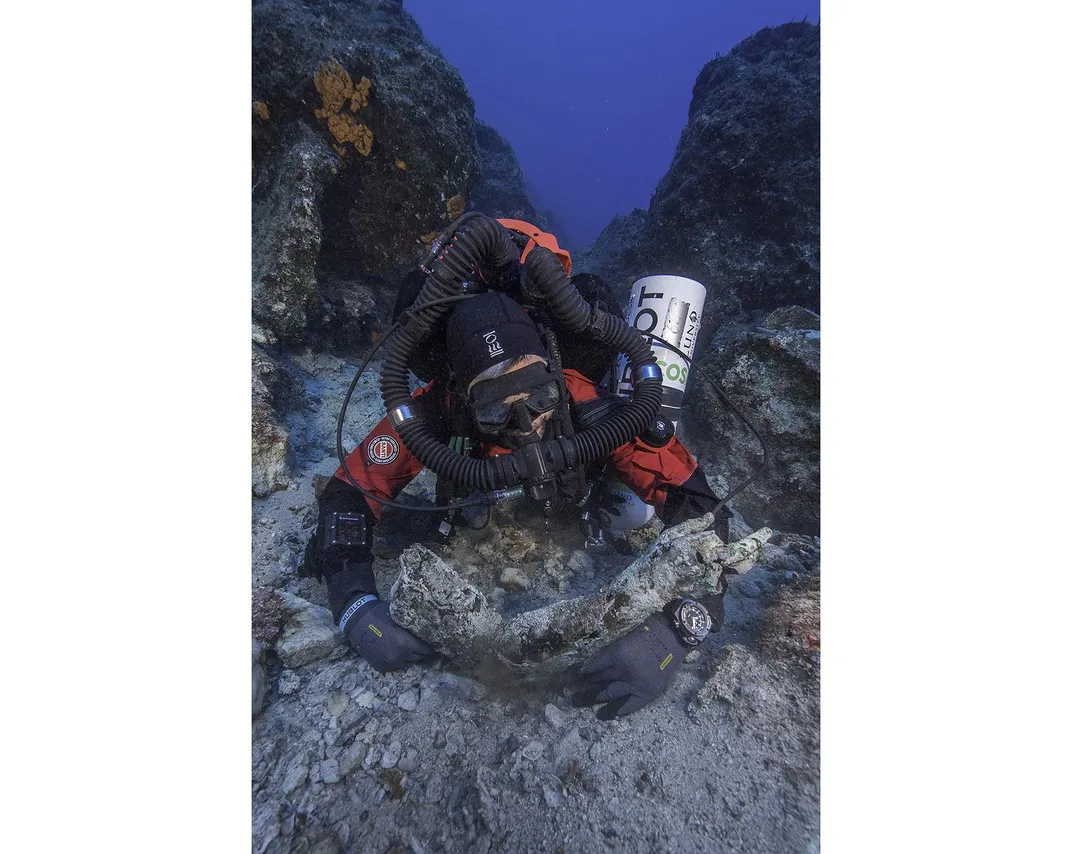

The “Return to Antikythera Expedition,” conducted by experts from the Greek Ephorate of Underwater Antiquities and Lund University in Sweden, took place over 16 days last month. Divers found the disembodied arm using a “bespoke underwater metal detector,” Sample writes, which has also indicated the presence of several bronze statues lying beneath heavy boulders. Brendan Foley, co-director of the team from Lund University, tells Sample that “a minimum of seven, and potentially nine” bronze sculptures could be submerged beneath the seabed.

The dive was carried out in an unexplored area of the wreckage, according to Jo Marchant of Nature. Previous trips to the site have revealed that the ship was packed with valuables before it went down. Over the years, archaeologists have found jewellery, luxurious glassware, pottery, and a beautiful bronze statue known as the “Antikythera Youth.” But the most famous artifact pulled from the wreckage is arguably the Antikythera Mechanism, a remarkable device that could predict eclipses and showed the movement of the sun, moon and planets.

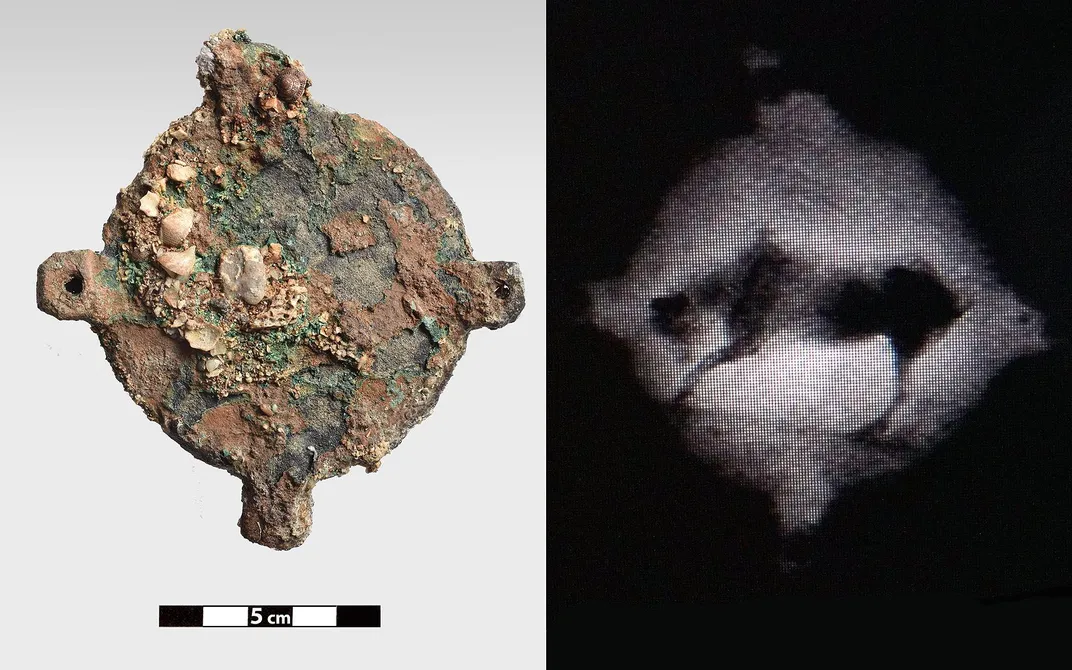

Researchers who embarked on the most recent expedition found a sarcophagus lid made of red marble, a silver tankard, fragments of the ship’s frame, a human bone and a curious bronze disc that was initially believed to be a missing part of the Antikythera Mechanism. Experts X-rayed the disc expecting to find gear wheels, but instead they discovered the image of a bull stamped onto the object. It is possible, then, that the artifact was a decorative element that was once affixed to a shield, a box, or even to the body of the ship.

The star discovery of the excavation was the bronze arm, now rusted and mottled from the centuries it spent submerged in water. The arm is slim and its hand appears to be making a turning gesture, which may indicate that the statue once depicted a philosopher, according to Marchant.

Archaeologists are keen to scout out other the bronze relics that were detected at the Antikythera shipwreck because relatively few classical bronze sculptures have survived to the present day. As Sample explains in the Guardian, bronze artworks were often recycled and repurposed during the ancient period, making the discovery of ancient bronzes a rare occurrence.

“We think of the [bronze sculptures] from the sea as those that got away,” Jens Daehner, associate curator of antiquities at the J. Paul Getty Museum, tells Sample. “Any chance to recover more Greek sculptures in any medium, but particularly in bronze, should not be missed.”

But unearthing the sculptures from Antikythera is easier said than done. The metal objects are covered by boulders weighing several tons, which may have rolled onto the shipwreck during an earthquake in the 4th century A.D. To remove the boulders, divers will have to either haul them away or crack them open—a laborious effort in either case.

Fortunately, archaeologists do not appear to be cowed by the difficult task ahead of them. The team plans to return to the wreckage in the spring of 2018, at which time they will continue their search for the bronze sculptures and, excitingly, move into the hold of the shipwreck.