Nation Mourns Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Who Broke Barriers and Became a Feminist Icon

The Supreme Court justice, who died at 87, “inspired women to believe in themselves,” says the Smithsonian’s Kim Sajet

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/fc/a7/fca778e2-6e25-433e-9686-3d0c5e7addb3/rbg-1.jpg)

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, the second woman to serve on the Supreme Court and an iconic advocate for gender equality, died Friday at her Washington, D.C. home. She was 87. The cause was complications of metastatic pancreatic cancer.

“Our Nation has lost a jurist of historic stature,” said Chief Justice John G. Roberts, Jr. in a Supreme Court statement. “We at the Supreme Court have lost a cherished colleague. Today we mourn, but with confidence that future generations will remember Ruth Bader Ginsburg as we knew her—a tireless and resolute champion of justice.”

Ginsburg served 27 years on the nation’s highest court, becoming its most prominent member. Her death will have “profound consequences” for the future of the U.S. legal system and the nation, writes Nina Totenberg for NPR, as politicians will fight to determine her successor under the spotlight of the upcoming presidential election.

“Ruth Bader Ginsburg did not just create history, she embodied the true origins of the word’s original meaning by acquiring knowledge through years of inquiry and research and adding her own opinions,” says the Smithsonian's Kim Sajet, the director of the National Portrait Gallery. “Armed with a fierce intelligence and a love of analytical reasoning, she fought passionately for all Americans to have equal representation under the law and inspired women in particular, to believe in themselves to make positive change.”

Born in a working-class Brooklyn home in 1933, Ginsburg faced discrimination on the basis of sex at every step along her path to the Court.

After her admission to Cornell University, on a full scholarship at age 17, she met her husband, Martin D. Ginsburg, a lawyer who supported her career. Together they had two children and were married for 56 years, until Martin died of cancer in 2010. “He was the first boy I knew who cared that I had a brain,” Ginsburg would often joke. After graduating top in her class from Columbia Law School, Ginsburg struggled to find a New York City law firm that would hire her. “I was Jewish, a woman, and a mother. The first raised one eyebrow; the second, two; the third made me indubitably inadmissible,” she recalled in 1993.

From 1963, Ginsburg taught law on Rutgers Law School’s Newark campus. In 1972, Ginsburg became the first woman named a full professor at Columbia Law School and co-founded the ACLU’s fledgling Women’s Rights Project.

With the ACLU, Ginsburg began in earnest the work that would define her career: the fight for gender equality in the law. From 1973 to 1978, Ginsburg argued six cases about gender discrimination in front of the Supreme Court. She won five.

Ginsburg’s feminist beliefs were strongly influenced by Swedish feminism, which she researched extensively after graduating from Columbia. She had also read Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex, a cornerstone feminist text, which shaped her burgeoning feminism in the 1960s, reported Smithsonian magazine's Lila Thulin.

Ginsburg was appointed to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit in 1980. In 1993, President Bill Clinton nominated Ginsburg for the Supreme Court, saying that he believed she would be a “a force for consensus-building.” Indeed, Ginsburg was known for forging close companionships with members of the court. She bonded with the late conservative Justice Antonin Scalia over their shared love of opera. (Their friendship even inspired an operetta in their honor.)

In 1993, Ginsburg wrote the majority opinion for United States v. Virginia, where the Court voted 7 to 1 to strike down the male-only admissions policy at Virginia Military Institute. The state had argued that women would not be able to meet the physical demands of the Institute. Ginsburg agreed that many women would not; however, she argued that those who could meet the physical qualifications should be allowed entry to the prestigious institution.

In the opinion—what the Time’s Linda Greenhouse calls the “most important of her tenure”—Ginsburg argued that in barring women from attending the Institute, the state was violating the Fourteenth Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause. “Generalizations about ‘the way women are,’ estimates of what is appropriate for most women, no longer justify denying opportunity to women whose talent and capacity place them outside the average description,” she wrote.

With the decision, the Court effectively struck down any law that “denies to women, simply because they are women, full citizenship stature—equal opportunity to aspire, achieve, participate in and contribute to society based on their individual talents and capacities,” as Ginsburg wrote.

Some of Ginsburg’s most memorable opinions were her withering dissents, as Marty Steinberg notes for CNBC. In Gonzales v. Carhart, the Court voted to uphold Congress’ Partial-Birth Abortion Ban Act of 2003, which outlawed the procedure. Ginsburg, in her dissent, wrote that the ruling “tolerates, indeed applauds” federal intervention into a procedure that some doctors deemed necessary and proper in certain cases.

“The court deprives women of the right to make an autonomous choice, even at the expense of their safety,” she wrote. “This way of thinking reflects ancient notions about women’s place in the family and under the Constitution—ideas that have long since been discredited.”

As historian Jill Lepore writes in the New Yorker, Ginsburg’s legal track record fundamentally altered the landscape of American civil rights. “Born the year Eleanor Roosevelt became First Lady, Ginsburg bore witness to, argued for, and helped to constitutionalize the most hard-fought and least-appreciated revolution in modern American history: the emancipation of women,” Lepore writes.

Lepore adds: “Aside from Thurgood Marshall, no single American has so wholly advanced the cause of equality under the law.”

By the time Ginsburg had reached her 80s, she had also become a pop culture icon. Her life story served as the basis for books, a documentary, and more. In 2018, a story about one of her first gender-discrimination cases, Moritz v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, was made into a Hollywood biopic starring Felicity Jones, On the Basis of Sex.

In 2013, a law student named Shana Knizhnik dubbed Ginsburg the “Notorious R.B.G.” as a riff on the name of the Brooklyn-born rapper, The Notorious B.I.G. The nickname—and R.B.G. herself—went viral. Ginsburg’s trademark glasses, piercing stare and decorative collar appeared in tattoos, bumper stickers, tote bags, coffee mugs, Halloween costumes and music videos.

At five feet tall, and weighing about 100 pounds, Ginsburg’s frail appearance could be deceptive. She was strong, as her longtime personal trainer would attest, and her rigorous workout routine inspired parodies and instruction manuals.

For years, the Justice dealt with seemingly endless health scares in the public eye. She had surgery for early-stage colon cancer in 1999, just six years after her appointment to the Supreme Court. In subsequent years, she underwent surgeries and rounds of chemotherapy to fend off pancreatic cancer, lung cancer, a return of pancreatic cancer and liver lesions.

During President Obama’s second term, as Ginsburg turned 80, she dismissed calls to retire so that a Democratic president could put forth her replacement. “She had planned, in fact, to retire and be replaced by a nominee of the first woman president because she really thought Hillary Clinton would be elected,” NPR’s Totenberg told CNN anchor Anderson Cooper on Friday.

Ginsburg announced in July that her cancer had returned and that she was undergoing chemotherapy. “I have often said I would remain a member of the Court as long as I can do the job full steam,” Ginsburg said in a statement. “I remain fully able to do that.”

On Friday evening, scores of people gathered for a candlelit vigil on the steps of the Supreme Court, bearing flowers and signs, reports Jacy Fortin for the New York Times. As NPR's Scott Simon observed, Ginsburg died on Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year and on the marble steps of before the massive pillars of the Court building, some gathered to sing “Amazing Grace,” and others recited the Kaddish, the Jewish prayer for the dead.

“Ginsburg’s Jewish heritage taught her that each successive generation must not just build upon the legacy of those who had come before them but fight to maintain and expand their civil rights into the future,” says Sajet.

“Young people should appreciate the values on which our nation is based, and how precious they are,” Ginsburg noted in 2017, because “if they don’t become part of the crowd that seeks to uphold them. . . no court is capable of restoring it.”

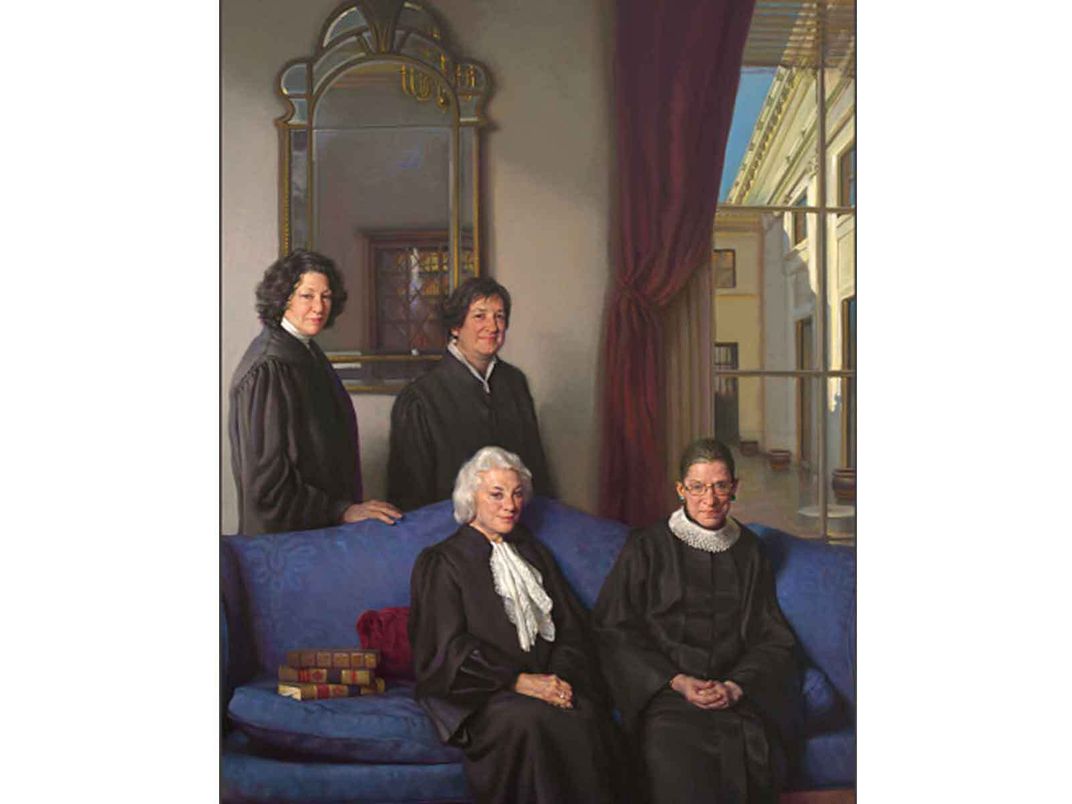

Read the "In Memoriam" tribute to the life of Ruth Bader Ginsburg, featuring The Four Justices portrait by Nelson Shanks, from Smithsonian's National Portrait Gallery.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)