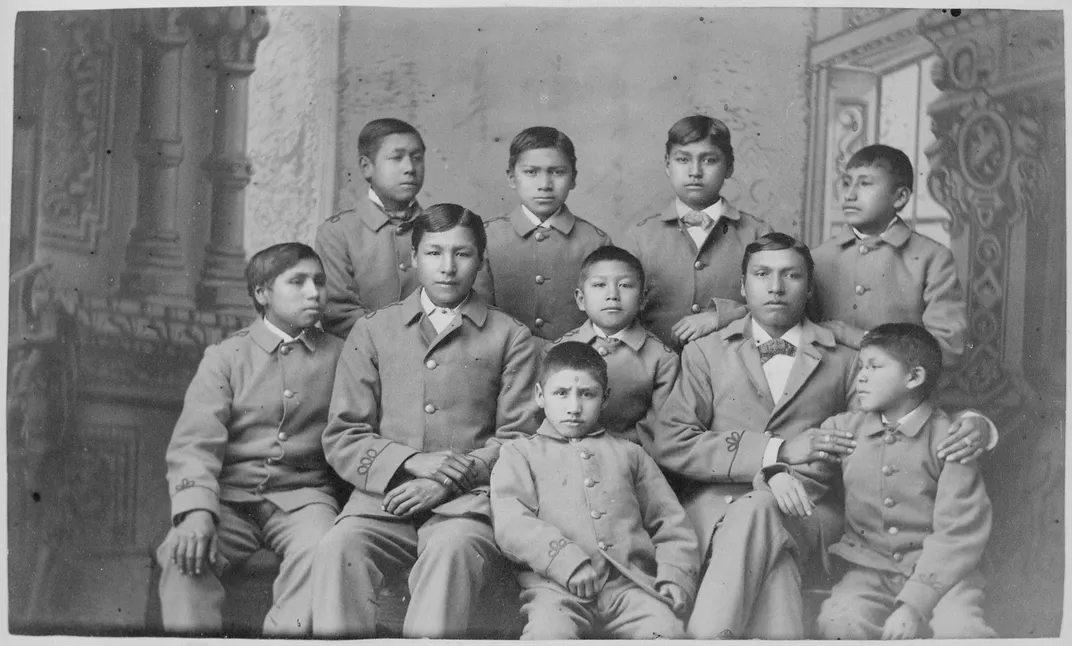

Remains of Ten Native American Children Who Died at Government Boarding School Return Home After 100 Years

The deceased were students at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, whose founder’s motto was “kill the Indian, and save the man”

:focal(775x541:776x542)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/22/9b/229b86bc-3ac4-4230-9dd7-94181f796a48/photograph_of_capt_pratt_and_students_at_the_carlisle_industrial_school.jpg)

After nearly a century, the remains of ten Native American children buried in a Pennsylvania borough will be disinterred and returned to their families, reports Rebecca Johnson for the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

Archaeologists began the delicate disinterment process this past weekend. Some family members have already traveled—or will soon travel—to Carlisle to accompany the remains on their journey home. The cemetery grounds will likely remain closed to visitors through July 17.

These ten children number among the 10,000 or so enrolled in the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, the first government-run boarding school for Native American students. Civil War veteran Richard Henry Pratt founded the institution in 1879 to “civilize” children from Indigenous tribes around the country—in other words, a project of forced assimilation to Euro-American culture, or cultural genocide. (Patterson believed his mission was to “kill the Indian, and save the man,” as he declared in an 1892 speech.)

One of the individuals set to return home is Sophia Tetoff, a member of an Alaskan Aleut tribe who died of tuberculosis in 1906, when she was around 12 years old. Five years earlier, she had traveled more than 4,000 miles from Saint Paul Island in the Bering Sea to Carlisle, writes her great-niece Lauren Peters in an op-ed for Native News Online.

Per a United States Army notice, nine of the children belonged to the Rosebud Sioux Tribe in South Dakota. Listed with their English names first and their Native names, which they were forced to give up, in parentheses, the deceased children are Lucy Take the Tail (Pretty Eagle); Rose Long Face (Little Hawk); Ernest Knocks Off (White Thunder); Dennis Strikes First (Blue Tomahawk); Maud Little Girl (Swift Bear); Friend Hollow Horn Bear; Warren Painter (Bear Paints Dirt); Alvan (also known as Roaster, Kills Seven Horses and One That Kills Seven Horses); and Dora Her Pipe (Brave Bull).

Until it closed in 1918, the Carlisle served as a model for more than 300 similar institutions across the country. Between 1869 and the 1960s, the government coerced, and sometimes forced, Native families to send their children to residential schools run by federal administrators and religious organizations such as the Roman Catholic Church, notes the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition on its website.

Far from home, students learned English and how to read and write—but they also endured horrific treatment: As Nick Estes and Alleen Brown reported for High Country News in 2018, teachers punished the children for speaking Native languages and subjected them to neglect, malnourishment and solitary confinement, as well as other forms of physical and sexual abuse.

More than 180 Native children died at Carlisle, often from a combination of malnourishment, sustained abuse and disease brought on by poor living conditions. According to Jenna Kunze of Native News Online, viewers can access enrollment cards, death notices and other clippings related to the deceased students through Dickinson College’s Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center.

One article published in the Eadle Keatah Toh, a newspaper run by and for Carlisle students, describes Dennis Strikes First, who arrived at the school on October 6, 1879, and died of pneumonia on January 19, 1887, as a “bright, studious, ambitious boy, standing first in his class, and of so tractable a disposition as to be no trouble to his teachers.”

Another clipping describes Maud Little Girl as a “bright, impulsive, warm-hearted girl, much loved by her school mates.” She and Ernest Knocks Off both died on December 14, 1880.

Family members of the deceased children have been advocating for the remains’ return for years, Barbara Lewandrowski, a spokeswoman for the Office of Army Cemeteries, tells the Post-Gazette. Since 2016, she adds, dozens of Native families have formally requested that their relatives’ remains be returned from Carlisle.

This is the U.S. Army’s fourth disinterment project at Carlisle in the last four years, reports the Associated Press (AP). The Army fully funds the process, including travel expenses for family members of the deceased, forensics, and reburial costs—a total amounting to about $500,000 per year.

“The Army’s commitment remains steadfast to these nine Native American families and one Alaskan Native family,” says Karen Durham-Aguilera, executive director of Army National Military Cemeteries, in a statement, as quoted by Steve Marroni of Penn Live. “Our objective is to reunite the families with their children in a manner of utmost dignity and respect.”

Also on Tuesday, Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland—the first Native American person to serve as a cabinet secretary—announced plans to investigate the “troubled legacy of federal boarding school policies,” per a statement. Earlier this month, in the aftermath of the discovery of 215 Native children buried at the Kamloops Indian Residential School in British Columbia, Haaland, whose great-grandfather attended the Carlisle school, penned a Washington Post op-ed calling for the country to learn from its history.

“The lasting and profound impacts of the federal government’s boarding school system have never been appropriately addressed,” she wrote. “This attempt to wipe out Native identity, language and culture continues to manifest itself in the disparities our communities face, including long-standing intergenerational trauma, cycles of violence, and abuse, disappearance, premature deaths, and additional undocumented physiological and psychological impacts.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/bf/74/bf740127-cc00-4324-b1c3-ea5c15b63b13/graves.jpeg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/40/70/407036d1-047d-4fe3-9066-f96bbb5c554d/lossy-page1-2560px-carlisle_indian_school_band_seated_on_steps_of_a_school_building_carlisle_pennsylvania_1915_-_nara_-_518927tif.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)