Paris Zoo Unveils Bizarre, Brainless ‘Blob’ Capable of Learning—and Eating Oatmeal

Physarum polycephalum is known as a slime mold, but it is not in fact a fungus. It’s also not a plant. Or an animal.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/46/75/4675fb7c-e8fd-456e-a45e-e98a8bf24238/gettyimages-1176167718.jpg)

The Paris Zoological Park is home to some 180 species, many of which would be considered standard zoo fare: zebras, giraffes, penguins, toucans, turtles and the like. But this week, the Zoological Park will unveil a new exhibit featuring a bizarre creature that has surprised and puzzled scientists for decades. It’s formally known as Physarum polycephalum, but zoo staff have dubbed it the “blob.”

Physarum polycephalum is a yellow-hued slime mold, a group of organisms that are not, in spite of their name, fungi. Slime molds also aren’t animals, nor are they plants. Experts have classified them as protists, a label applied to “everything we don't really understand,” Chris Reid, a scientist who has studied slime molds, told Ferris Jabr of Scientific American back in 2012.

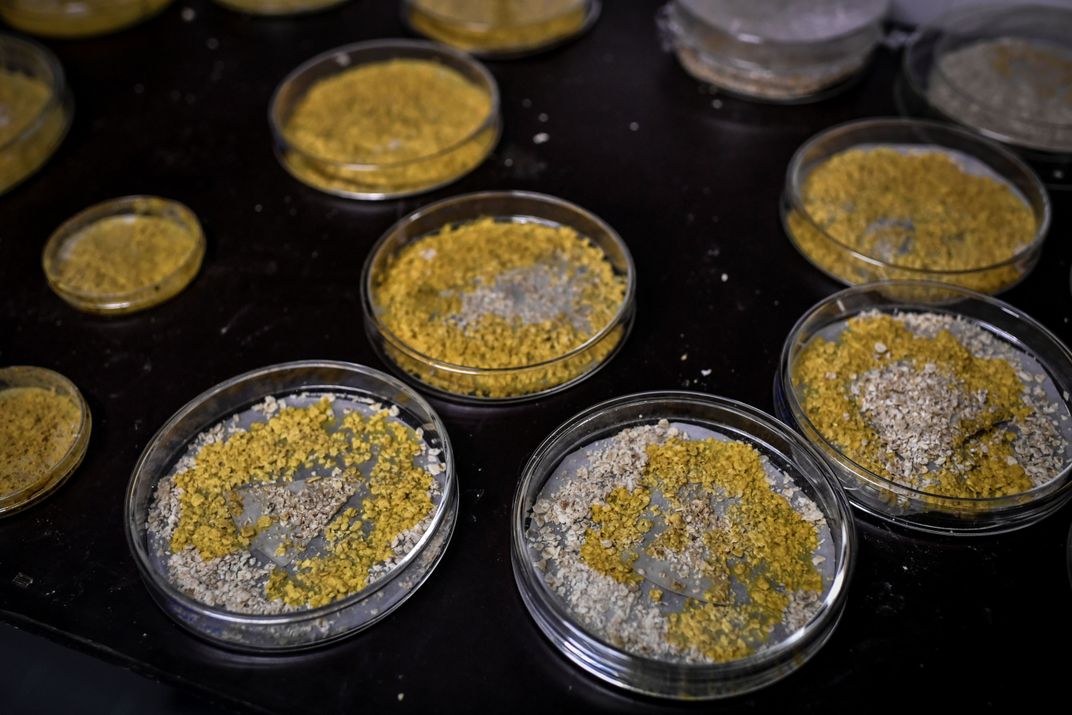

Like other slime molds, P. polycephalum is a biological conundrum—and a wonder. It’s a single-celled organism with millions of nuclei that creeps along forest floors in search of bacteria, fungal spores and other microbes. It can detect and digest these substances, but it doesn’t have a mouth or stomach. The Paris Zoological Park grew its organism in petri dishes and fed it oatmeal, which it seemed to like, reports CNN's Julie Zaugg. Zoo staff named the creature the “blob” after a 1958 horror B-movie, in which a gloopy alien lifeform descends upon a Pennsylvania town and devours everything in its path.

P. polycephalum can be blob-shaped, but it can also spread itself into thin, vein-like tendrils. Separate cells can merge if their genes are compatible, according to Mike McRae of ScienceAlert, and organisms heal quickly if cut in half. Compounding its oddities, P. polycephalum has nearly 720 distinct sexes.

But perhaps the most remarkable thing about P. polycephalum is that it possesses a kind of intelligence—though it has no brain. Research has shown, for instance, that the organism can find the shortest path through a maze with food at its start and end. By leaving a trail of slime in its wake, P. polycephalum avoids areas that it has already visited—a type of “externalized spatial ‘memory,’” scientists say. A 2016 study found that P. polycephalum could learn to avoid quinine or caffeine, known repellants for the organism.

“Many of the processes we might consider fundamental features of the brain, such as sensory integration, decision-making and now, learning, have all been displayed in these non-neural organisms,” the study authors wrote.

P. polycephalum is thought to have existed for around a billion years, but according to Zaugg, it first captured the public’s attention in the 1970s, when it showed up in a Texas woman’s backyard. The 1970s specimen didn’t last long, but those who are curious about the new blob will be able to see it at the Paris Zoological Park starting October 19. After growing the organism in petri dishes, staff grafted it onto tree bark and placed it in a terrarium.

“It thrives in temperatures oscillating between 19 and 25 degrees Celsius (66 to 77 degrees Fahrenheit) and when humidity levels reach 80 percent to 100 percent,” says staff member Marlene Itan, per Zaugg.

With its new exhibit, the Zoological Park hopes to introduce visitors to this remarkable creature, which is far more complex than its blob-like appearance might indicate. As Bruno David, director of the Paris Museum of Natural History, tells Reuters, “[P. polycephalum] behaves very surprisingly for something that looks like a mushroom.”