Landmark Exhibition Brings Victor Hugo’s Forgotten Drawings Into Focus

The famed French author produced some 4,000 brooding, tempestuous artworks during his lifetime

Throughout the course of his luminous career, Victor Hugo wrote prolifically: He produced poems and plays, searing political pamphlets and, of course, celebrated novels like The Hunchback of Notre-Dame and Les Misérables. Less well known are Hugo’s vast collections of drawings, which he worked on zealously while in exile during Napoleon III’s reign. Now, Jori Finkel reports for the Art Newspaper, a new exhibition at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles puts center focus on his artwork, considering his drawings within the wider scope of his creative output.

Called Stones to Stains: The Drawings of Victor Hugo, the show features 75 drawing and photographs sourced from several major European institutions and a few American ones, including the Musée d’Orsay, the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, the Met and the Art Institute of Chicago. Notably, Hugo’s artworks have only been featured once before in an exhibition stateside, for a 1998 show at the Drawing Center in New York.

The works featured in Stones to Stains tell an intriguing story of Hugo’s preoccupations and techniques as an artist, but they represent only a fraction of his artistic output. According to Daniel Schindel of the Observer, Hugo created more than 4,000 drawings in his lifetime, 3,000 of which have survived to the present day.

For Hugo, drawing was a private endeavor; he didn’t want his artistic pursuits to distract from his writing. So he drew for family, friends and for himself—stormy, brooding works, rendered not only in dark ink, but also in more experimental materials like coffee grounds and soot.

On display at the Hammer are landscapes of jagged cliff sides, a depiction of a castle being struck by lightning and a haunting, shadowy sketch of a man hanging from a scaffold.

Hugo's most prolific artistic period began after he fled from France in the early 1850s. The author was immersed in the politics of the country’s capital city; in 1848, he was elected deputy for Paris in the Constituent Assembly and later, in the Legislative Assembly. Though he initially threw his support behind Prince Louis-Napoleon, the nephew of Napoleon I who was elected president in 1848, Hugo’s enthusiasm waned as Louis-Napoleon shifted toward an authoritarian regime. After Louis-Napoleon staged a coup in 1851, installing himself as emperor under the regnal name Napoleon III, Hugo escaped to Brussels and, later, to the islands of Jersey and Guernsey in the English Channel.

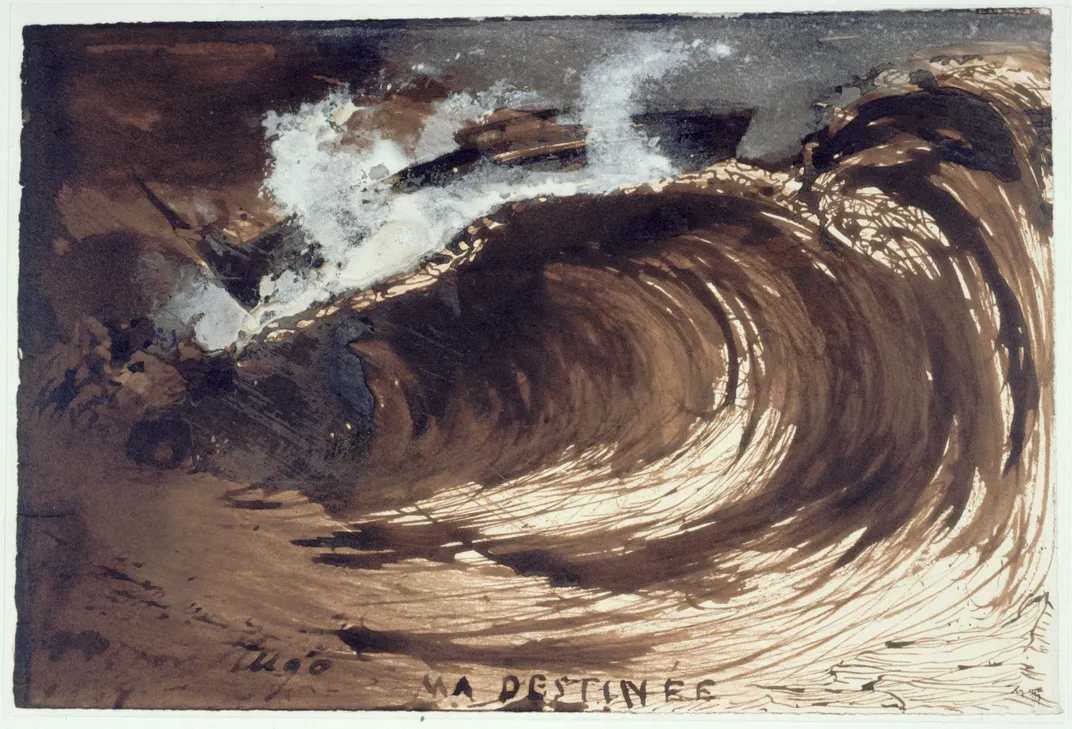

It is tempting to ascribe the mood of Hugo’s drawings to the tumult of these years. In an 1867 piece, a huge, frothy wave curls ominously into the sky, poised to crash at any moment. It is titled “Ma destinée”—My destiny.

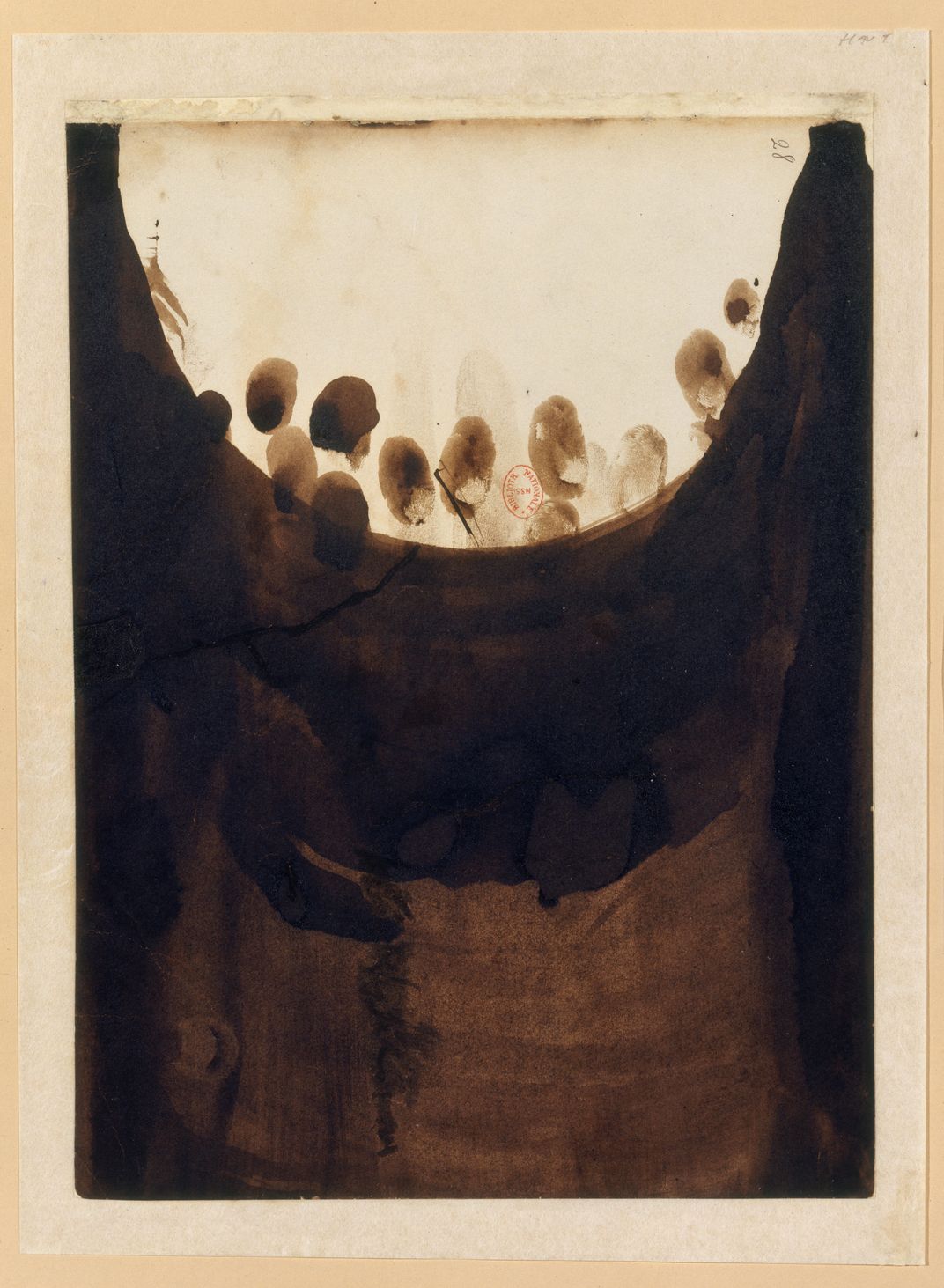

But it wasn’t all doom and gloom. As Allegra Pesenti, co-curator of the exhibition, says in a statement, Hugo was a “dreamer and an idealist,” and his drawings reflect his curiosity and experimental inclinations. Hugo bolstered his compositions with stencils and collages, using leaves, lace and even his fingertips to create impressions. He also liked to soak or turn the papers on which he drew, letting the ink flow into spontaneous shapes and taches, or stains. These works, Schindel writes, “are a drastic break from many conventions of the period, in some ways presaging expressionism and abstract art.”

Though he rarely exhibited his drawings in public, Hugo’s art elicited praise from the likes of van Gogh and Delacroix. But perhaps Hugo’s son Charles offers the most apt description of his father’s artistic oeuvre: “unexpected and powerful … often strange, always personal.”