Online Portal Reveals Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s Creative Process

The project’s launch coincides with a blockbuster Vienna retrospective celebrating the 450th anniversary of the Flemish old master’s death

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/dd/60/dd607965-542f-4b8c-b732-15603c8ffef4/gg_1016_201707_gesamt_cd.jpg)

On his deathbed, Pieter Bruegel the Elder beseeched his wife to burn a series of drawings the Flemish old master feared were too inflammatory, perhaps “because he was sorry,” suggests a 1604 biography by noted art historian Karel van Mander, or “he was afraid that on their account she would get into trouble.”

The subversive—and, to this day, little-understood—qualities of Bruegel’s work often took the shape of panoramic landscapes dotted with bursts of everyday activity. Alternately interpreted as celebrations or critiques of peasant life, Bruegel’s paintings feature a pantheon of symbolic details that defy easy classification: A man playing a stringed instrument while wearing a pot on his head could, for example, represent a biting indictment of the Catholic Church—or he could simply be included in hopes of making the viewer laugh.

“Inside Bruegel,” an ambitious restoration and digitization portal launched in October to coincide with the opening of the Kunsthistorisches Museum’s blockbuster Bruegel retrospective, aims to uncover the Renaissance painter’s underlying intentions. As Nina Siegal reports for the New York Times, the website features high-quality renderings of the Vienna institution’s 12 Bruegel panels, as well as scans of the details hiding below the final brushstrokes.

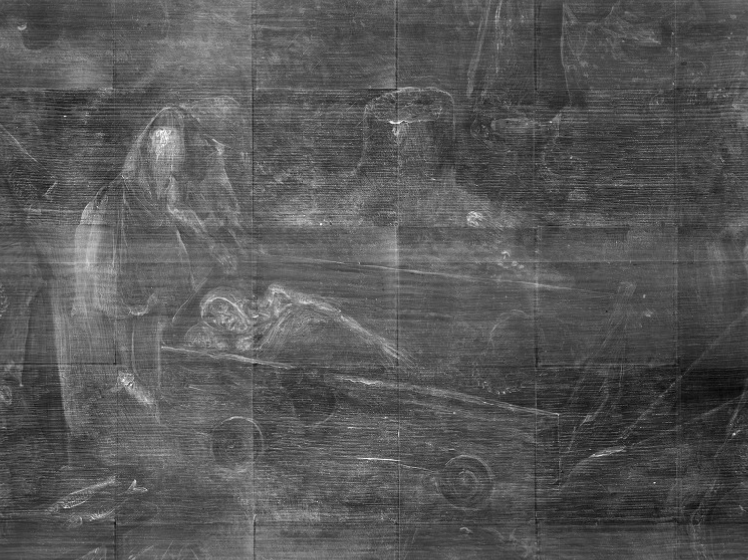

X-ray imaging of a 1559 work, “The Battle Between Carnival and Lent,” reveals macabre features masked in the final product, including a corpse being dragged in a cart and a second dead body lying on the ground. Infrared scans further highlight the small changes Bruegel made prior to completing the painting, with a cross adorning a baker’s peel transformed into a pair of fish. The cross blatantly refers to the church, while the fish—a traditional Lent delicacy—offers a subtler nod to Christ.

According to the project page, “Inside Bruegel” was launched in 2012 with support from the Getty Foundation’s Panel Paintings Initiative, which awards grants to burgeoning art conservators. Previously, the initiative enabled the creation of “Closer to Van Eyck,” a sweeping digitization of Jan and Hubert van Eyck’s 1432 masterpiece, “The Ghent Altarpiece,” or “Adoration of the Mystic Lamb.”

In addition to allowing visitors to take a closer look at Bruegel works as they’re known today, the portal features scans conducted with infrared reflectography, macro-photography in infrared and visible light, and X-radiography, affording scholars and art lovers alike an unprecedented glimpse into the artist’s creative process, handling and technique.

Sabine Haag, director of the Kunsthistorisches, tells Deutsche Welle that the various processes serve different purposes. Infrared photography, for example, makes signatures and underdrawings visible, while X-ray imaging allows researchers to examine the wooden panels on which Bruegel painstakingly layered his creations.

In a blog post published on the Kunsthistorisches’ website, curators detailed a few of the project’s most intriguing findings: Of the 12 panels, only one, “Christ Carrying the Cross,” retains its original format. The rest were cropped at some point following their creation, with someone actually taking a saw to the top and right edges of the 1563 “Tower of Babel.” In some cases, cropping fundamentally altered Bruegel’s “carefully calibrated composition,” drawing attention away from certain elements and bringing others to the forefront.

The corpses seen in the X-ray version of “The Battle Between Carnival and Lent” also offer evidence of later artists’ interventions. Sabine Pénot, a curator of Netherlandish and Dutch paintings at the Kunsthistorisches, tells the Times’ Siegal that Bruegel didn’t cover up the dead bodies himself; instead, an unknown entity likely blotted them out during the 17th or 18th century.

Interestingly, preparatory underdrawings for Bruegel’s early works, including “Carnival and Lent,” feature an immense array of details that Bruegel precisely translated into his brushstrokes. A year later, however, the artist’s underdrawings include far fewer details, eventually culminating in the Tower of Babel panel’s complete disregard for preparatory work.

"The investigations showed … that under the layers of paint, there were drawings that were hidden and have hardly been researched so far," Haag tells Deutsche Welle. "It was extremely exciting to see how Bruegel worked: if he normally primed the boards; if he made preliminary drawings; if changes were made."

In conjunction with the Bruegel exhibition, which joins 30 of the Netherlandish master’s extant panel paintings and almost half of his preserved drawings and prints, the online portal represents a significant contribution to our understanding of the enigmatic artist.

Still, as exhibition co-curator Ron Spronk, an art historian at Queen’s University in Canada, tells Siegal, it’s impossible to gauge Bruegel’s exact motivations. Was the painter an anthropologist of sorts “who wanted to show us images of peasants in their daily life, falling into the water, having a bowel movement in the grass,” or was he “pretty much just trying to make us laugh”?

“Inside Bruegel” has no firm answers. Instead, it serves as a portral into the old master's eclectic world, enabling amateur art detectives to form their own assessment of his lively—or, depending on your viewpoint, satirical, scintillating and perhaps even sacrilegious—scenes.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)