Newly Digitized Freedmen’s Bureau Records Help Black Americans Trace Their Ancestry

Genealogists, historians and researchers can now peruse more than 3.5 million documents from the Reconstruction-era agency

:focal(596x372:597x373)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a2/94/a29455ff-121e-4fb9-a6d6-8613173e932c/screen_shot_2021-08-25_at_11229_pm.png)

Anyone with an internet connection can now access more than 3.5 million records documenting the lives of free Black people during the Reconstruction period. Created by genealogy company Ancestry, the free online portal amounts to a treasure trove of information about Black communities in the United States between 1846 and 1878, reports Rosalind Bentley for the Atlanta Journal-Constitution (AJC).

The newly debuted tool will allow researchers to study the records of the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen and Abandoned Lands (also known as the Freedmen’s Bureau) with unprecedented ease. Though some of the documents, which are housed at the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) in Washington, D.C., have been digitized previously, the searchable database offers a new level of accessibility. Users can find the resource here.

Per the AJC, the portal allows researchers to search caches of documents simultaneously. Until now, scholars had to scour each state, county, city, category and so on individually, often by spending hours poring over microfilm records, as Melissa Noel writes for the Grio.

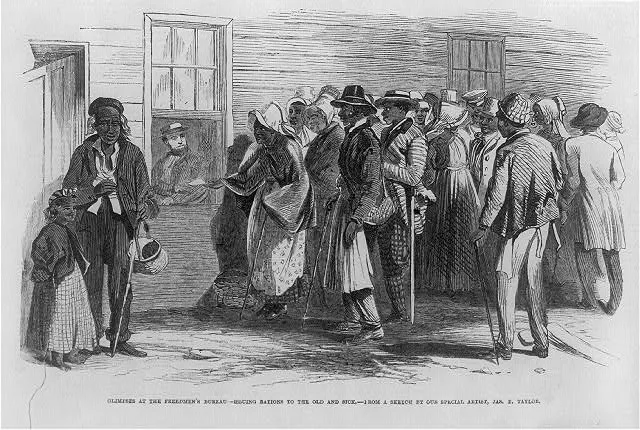

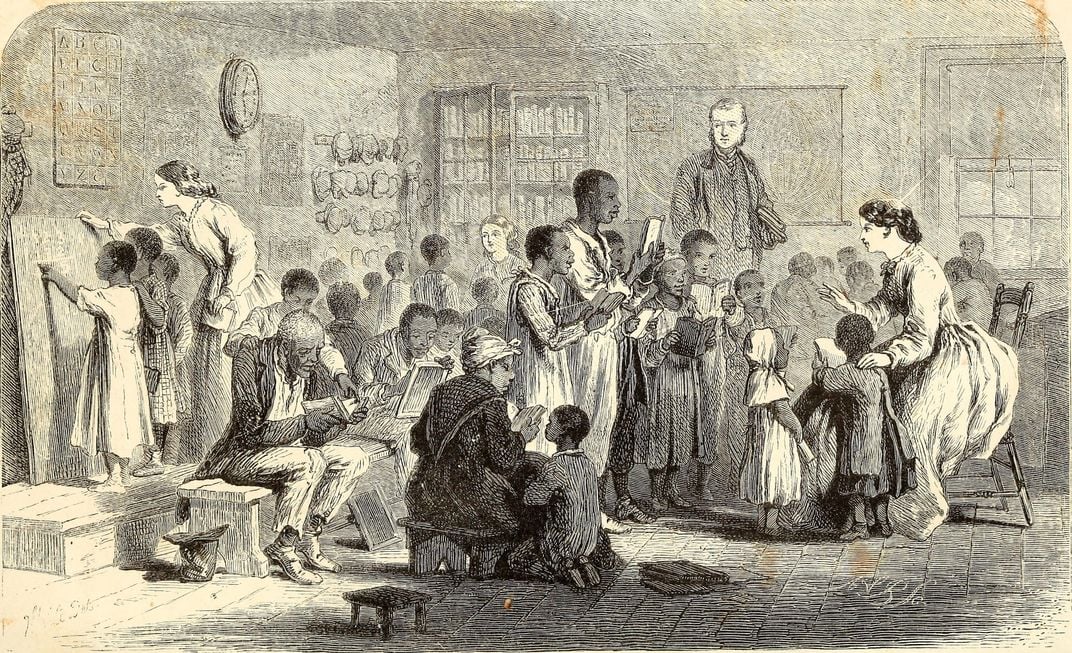

The Freedmen’s Bureau dates to the end of the Civil War—the bloodiest conflict in American history. Established by Congress in March 1865, the program offered education, medical care, food, clothing and labor contracts to displaced Southerners, including more than four million newly freed Black Americans. Bureau officials also helped the formerly enslaved locate their loved ones, investigate incidents of racist violence and legally marry their spouses, per the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture.

A social relief program of unprecedented scope, the bureau remained in operation for less than a decade. In 1872, pressure from white Southern legislators and the threat of vigilante violence (such as attacks by the Ku Klux Klan) led Congress to abandon the project.

Today, historians continue to debate the effectiveness of these short-lived relief efforts. But the millions of pages of records that officials produced during this period have become a boon for historians and genealogists eager to study their ancestors and learn more about the lives and concerns of newly freed Black people.

For many formerly enslaved people, bureau documents represented the first time their names were written down in official records of any kind, notes the AJC. Prior to 1870, U.S. censuses neglected to include the names of enslaved people, instead listing them statistically under their enslavers’ names or referring to them as numbers.

The bureau’s handwritten records are often unwieldy and difficult to read. As Allison Keyes reported for Smithsonian magazine in 2018, the Smithsonian Transcription Center offers ongoing opportunities for volunteers to translate the 19th-century cursive in more than 1.5 million image files into searchable text.

During a virtual roundtable announcing the Ancestry initiative, genealogist Nicka Sewell-Smith said, “I spent 14 years going through this collection going image by image.” Per the Grio, she added, “So with the [new, searchable] collection, in the manner in which it’s being released, that changes the game quite a bit for a lot of people.”

Stan Deaton, a senior historian at the Georgia Historical Society who was not involved in the Ancestry project, emphasizes the possibilities opened up by the portal.

“It’s hard to overstate how important this could be,” Deaton tells the AJC. “The Freedmen’s Bureau was … in many ways was the first social service agency.”

The historian adds, “So [the Ancestry project] is very important in capturing the lives of four million people who were newly freed and starting new lives in one of the greatest social changes in this country’s history. This could be a gold mine.”

Editor’s Note, August 27, 2021: This article has been updated to clarify how enslaved people were counted in the census prior to 1870.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/eb/d7/ebd7a447-50d8-4a69-b8fc-0ac1eb8fe502/2-hawkins-wilson-xl.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)