Nearly a Decade After Fukushima, Photos Capture Residents’ Bittersweet Return

A new photo series titled “Restricted Residence” features 42 thermal images of locals and their changed landscape

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/72/b3/72b32d7c-c270-4524-9143-bc743dc6c7b9/giles_price_restricted_residence_6.jpg)

When a catastrophic earthquake and tsunami triggered the release of radioactive material from Japan’s Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant in March 2011, locals didn’t have time to think. Officials wore intense radiation protection but told members of the public they weren’t at risk. Communities were uprooted to evacuation centers with higher radiation levels than their homes. And around 60 elderly residents died due to the stress of being moved from hospitals and care homes.

No radiation-related deaths occurred in the immediate aftermath of the disaster, but the psychological turmoil provoked by the event took its toll, with suicide rates increasing in the years following the accident.

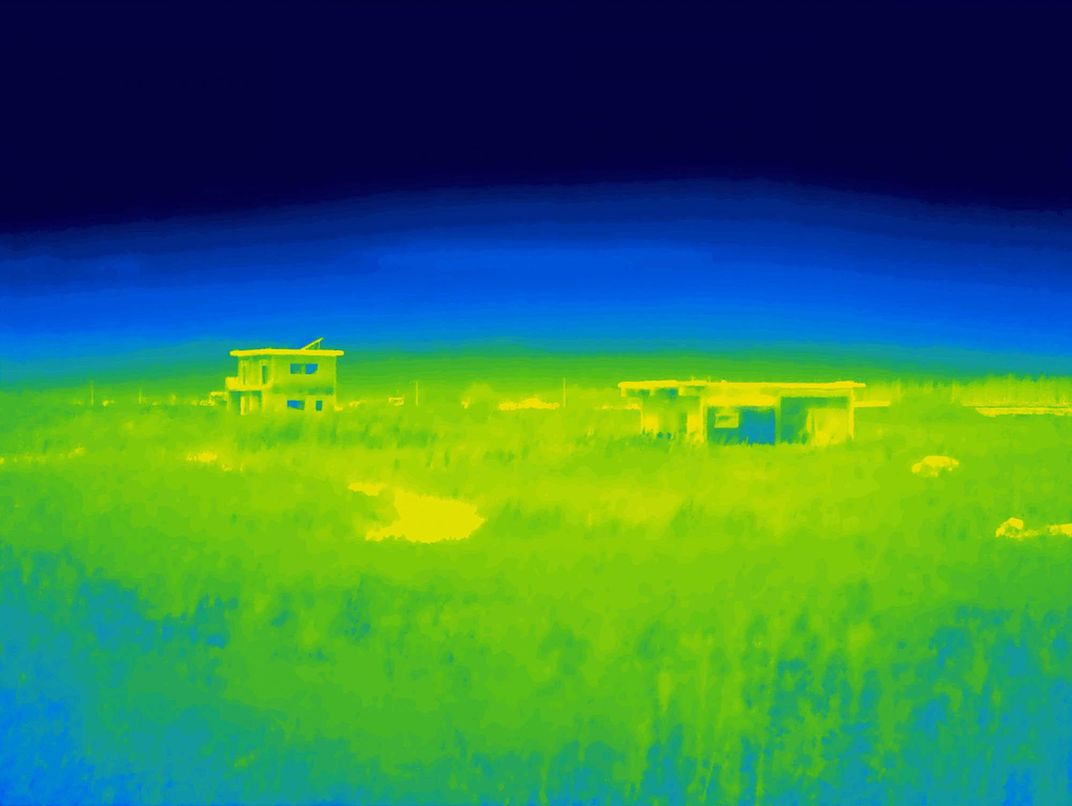

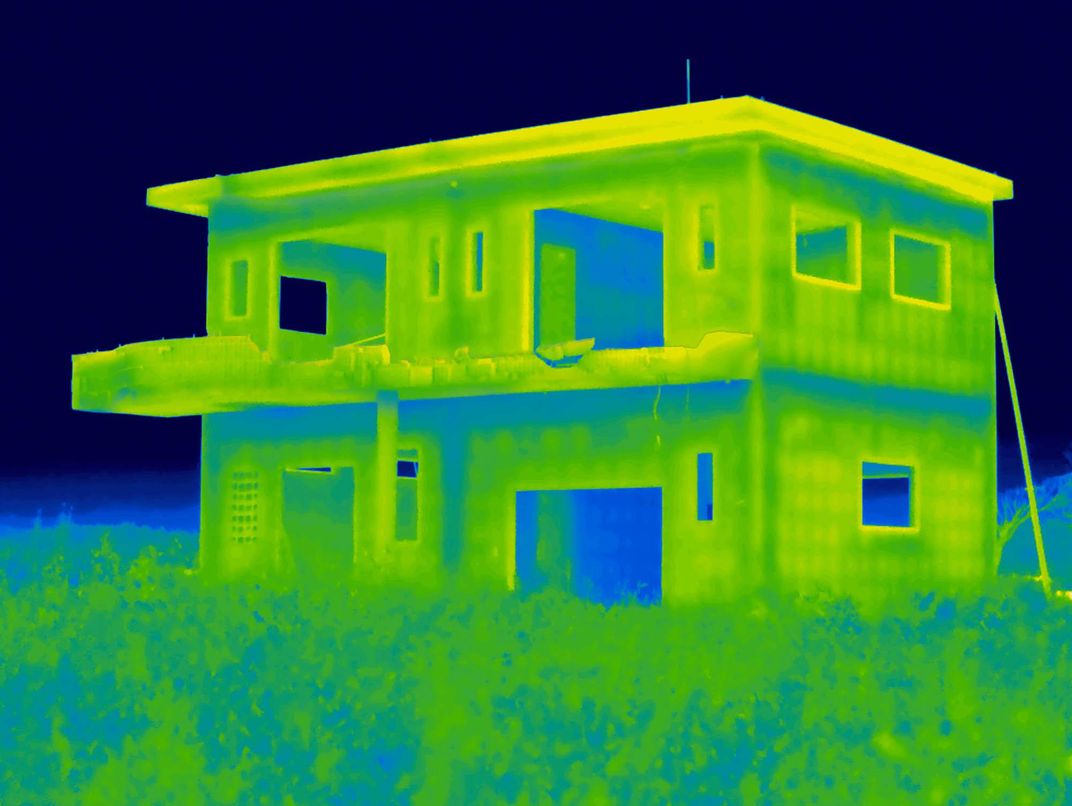

Restricted Residence, a new book by British photographer Giles Price, captures several hundred Japanese citizens’ return to the villages of Namie and Iitate after the Fukushima nuclear disaster. Released on January 16 at the Photographers’ Gallery in London, the monograph uses thermographic technology more commonly employed in medicine and industrial surveying to help viewers consider the hidden psychological impacts of manmade environmental disasters. Citing scientists’ uncertainty regarding radiation’s long-term effects, the photo series also highlights the ongoing debate over whether the Japanese government should incentivize people to return to their homes.

On March 11, 2011, a magnitude-9.0 earthquake struck 231 miles northeast of Tokyo. The tremor was a rare and complex double quake, lasting three to five minutes and shifting the island by about eight feet, according to the U.S. Geological Survey. The earthquake, later determined to be the largest to ever hit Japan, unleashed a tsunami with waves as high as 33 feet. Combined, the two natural disasters killed more than 20,000 people and destroyed roughly one million buildings in the region.

But the unforeseen failure of the nearby Fukushima plant would soon prove to be even more catastrophic. After the initial earthquake, the subsequent tsunami waves spilled over the plant’s 30-foot-tall sea wall and damaged the generator cooling system, reports Wallpaper’s Tom Seymour. The reactors’ cores overheated, melting the uranium fuel within and forcing engineers to release radioactive gases into the surrounding area rather than risk the reactors exploding. Ultimately, the Japanese government ordered the evacuation of more than 150,000 citizens living up to 80 miles away from the plant. The incident was the world’s largest nuclear disaster since Chernobyl.

In 2017, the Japanese government lifted evacuation orders outside of the “difficult-to-return” zone, which encompasses a 12-mile area around the nuclear plant, and began financially incentivizing residents to return. (Original estimates placed the initiative’s cost to taxpayers at $50 billion, but a 2016 analysis conducted by the Financial Times suggests the figure is closer to $100 billion.) Before the disaster, some 27,000 people had made their homes on the outskirts of this exclusion zone, living in the villages of Namie and Iitate.

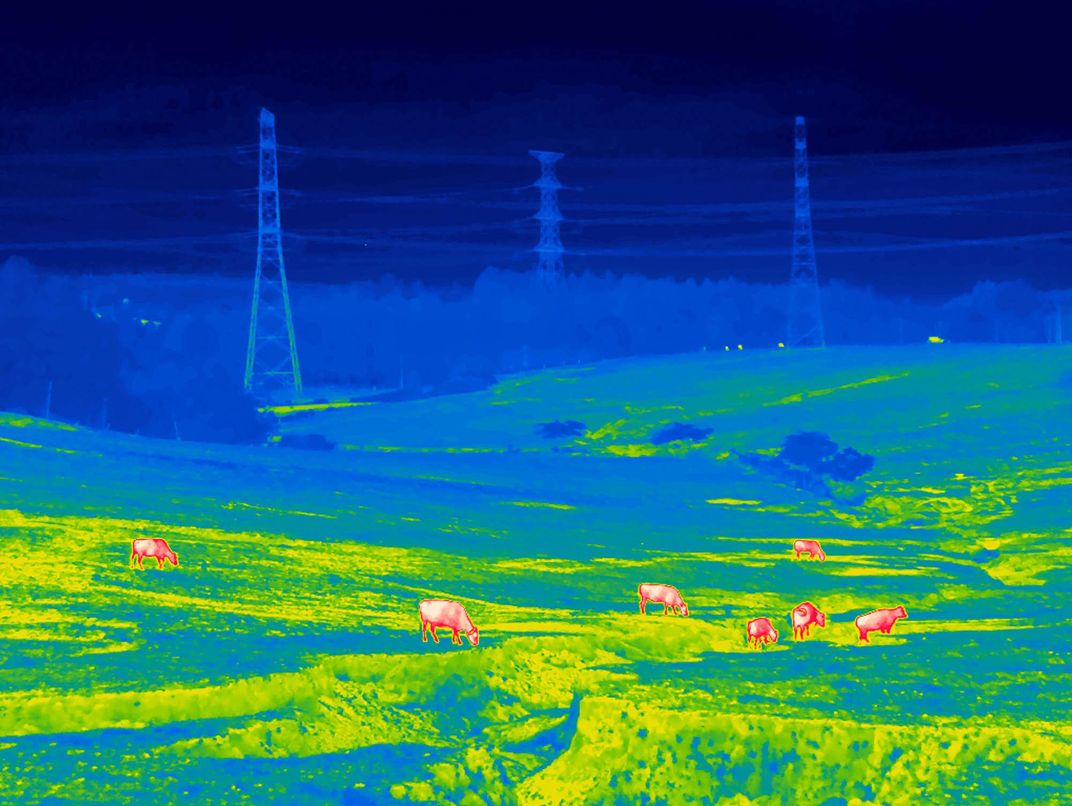

By depicting workers and the surrounding landscapes of these two towns, Restricted Residence explores the intersection of physical reconstruction and hidden uncertainty. The book features photographs of ordinary hard-working people, from mechanics to shopkeepers and office workers, cleaning up their neighborhoods and rebuilding their lives. Of particular interest are a taxi driver paid a government retainer because of his lack of customers and a farmer who spends his days tending to contaminated cattle he can’t sell but refuses to put down.

Price says he was fascinated by the region’s landscapes, specifically how deconstruction and radiation impacted the abandoned areas.

“When I started to think about how to approach the altered environment of the exclusion zone, it was the visual abstractness of the colors rendered by the technology which interested me, not its scientific applications,” he tells Ayla Angelos of It’s Nice That.

The photographer drew inspiration for the project from his own life. He joined the Royal Marines Commando at the age of 16, and a year later, served in Kurdistan toward the end of the 1991 Gulf War. With his camera in hand, Price photographed the landscape and his daily experiences while on tour; his snapshots are now on display at London’s Imperial War Museum.

Per It’s Nice That, Price was medically discharged after sustaining a life-changing injury in Iraq. But his time as a soldier helped him form a personal interest in photographing how landscapes connect to what he calls the “human-inflicted environment.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/0f/03/0f032a52-1afd-41f5-bbd1-d6f9cb01c3b2/giles_price_restricted_residence_10.jpg)

Previously, Price took aerial images in anticipation of the Rio and London Olympics. The series focused on the social, economic and environmental impacts of the changing landscape created by the games’ construction. Now, with the upcoming Summer Olympic Games taking place in Tokyo, Price is fascinated to see how the redevelopment of Fukushima is represented.

Fukushima will not only host an Olympic baseball match and six softball games, but will also initiate the Olympic torch relay, reports Marigold Warner for the British Journal of Photography. The organizers hope these events help economically improve the region while destigmatizing perceptions surrounding radiation disaster survivors.

Deep within the colors of Restricted Residence’s red-oranges and yellow-blues, Price strives to capture the undetectable.

“[T]here is […] something about the invisibility of radiation, and its potential to kill silently,” says Fred Pearce, a science and environmental writer, in the book’s accompanying essay. “[…] We have good reason to fear what we cannot see, or taste, or hear, or touch. If our senses offer no guide to the scale of the risk, we must assume the best or fear the worst.”

The normalcy of the photos is misleading, forcing viewers to look for something that isn’t present. Price invites visitors, in a brilliant fashion, to experience the unseen weight of the psychological burden while attempting to grasp the impact of radiation.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/37340836_1862108597212824_3071431907662102528_n.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/37340836_1862108597212824_3071431907662102528_n.jpg)