This Museum Made Art Out of a John Deere Harvester

‘Continuous Service Altered Daily’ finds life inside a familiar machine

Unless you’re reading this in the middle of nowhere, a quick glimpse around you will likely reveal an entire world of lifeless machines. Sure, they move, but these inanimate objects are mere collections of metal and mechanics, completely separate from human life. Or are they? Artist David Brooks doesn’t think so—and that’s why he took apart a John Deere combine harvester on the front lawn of The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum Ridgefield, Connecticut.

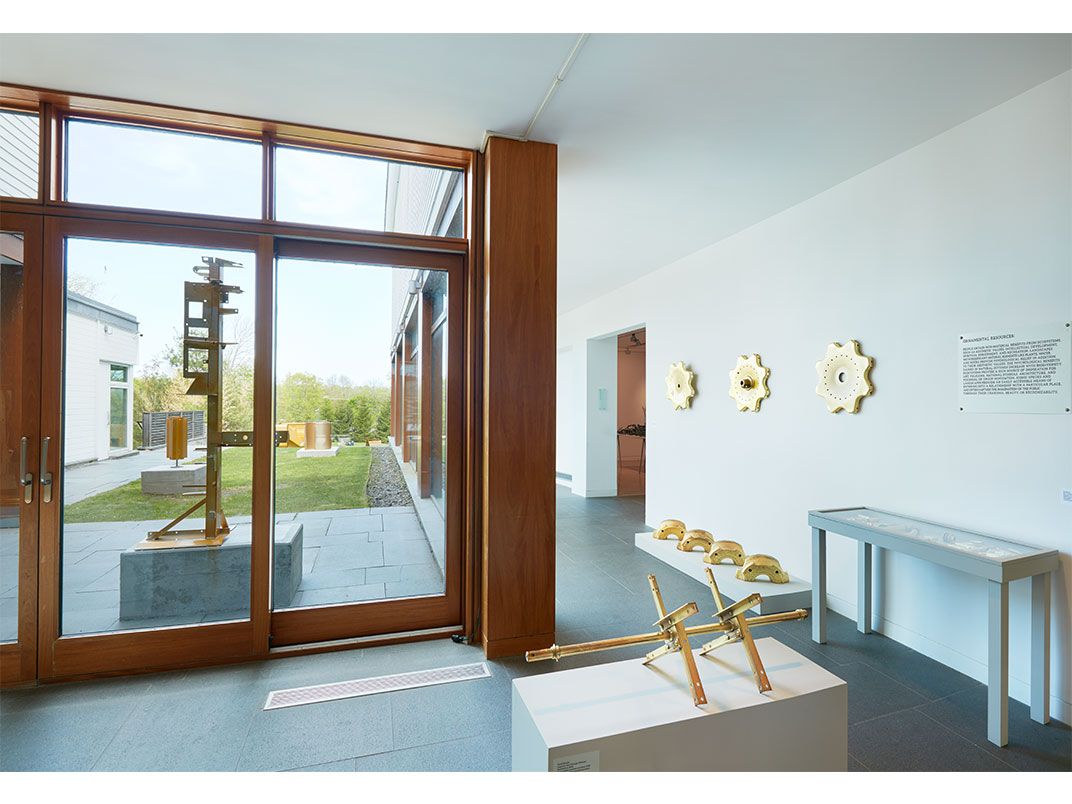

Brooks calls his installation, Continuous Service Altered Daily, “an asteroid field without beginning or end.” The exhibition features every single piece of a 1976 John Deere 3300 series combine harvester that Brooks disassembled and put on display throughout the museum, everywhere from the lawn to the innermost galleries. Some pieces are weathered; others have been brass-plated or coated with powder to preserve them. All are displayed as art.

So what’s the point? For Brooks, a look at the complicated guts of the combine is a chance to peer into its history, symbolism and artistic potential. Combine harvesters (better known as “combines”) are common sights in farm country, but when they were invented in the 1830s, they were big news. At the time, farmers had to use separate processes to reap, thresh and winnow crops. The new machine combined all three, taking some of the backbreaking labor out of farming, and this more efficient method allowed farms to turn from small-time operations into large industrial ventures. Today, combines are a common sight wherever there’s a grain crop.

After taking the entire machine apart, Brooks separated its parts into nine zones. He sees the combine as an ecosystem in and of itself, one that affects the human ecosystem as it engages in water purification, pollination, disease regulation, decomposition, air purification, habitat formation, photosynthesis (primary production), ornamental resources, and erosion and flood control. By treating its many pieces as sculpture, he’s making a statement about the complicated art of farming—one that feeds millions of Americans even as it makes irreversible impacts to their Earth.

Is the combine harvester a life-giving piece of art or just a machine? Find out for yourself: The exhibition will take over the museum until February 5, 2017.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erin.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erin.png)