Musée d’Orsay Renames Manet’s ‘Olympia’ and Other Works in Honor of Their Little-Known Black Models

Marie-Guillemine Benoist’s “Portrait of Madeleine,” previously titled “Portrait of a Black Woman,” hangs alongside Manet’s newly christened “Laure”

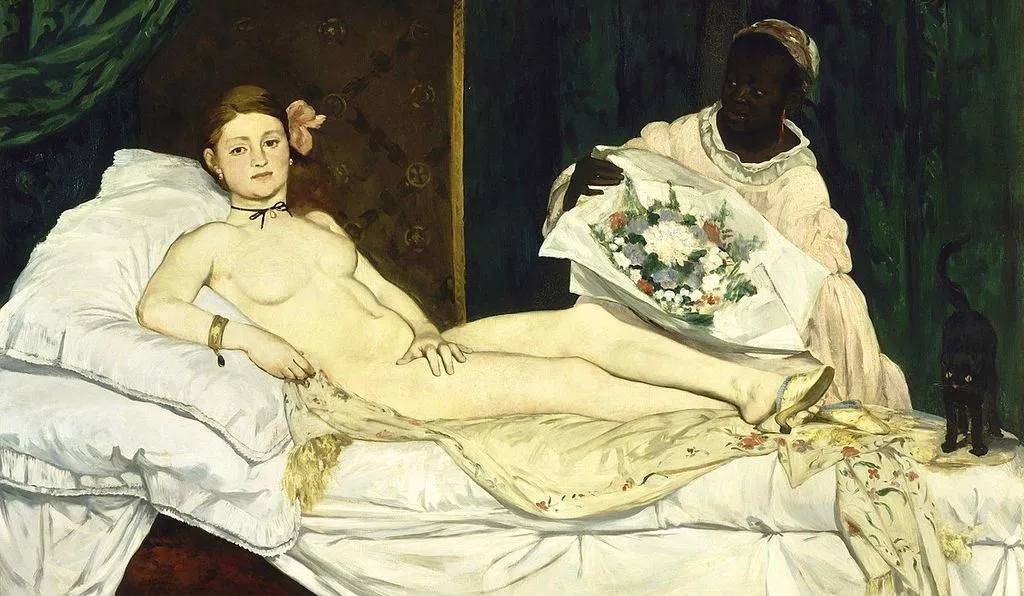

A new exhibition at the Musée d’Orsay places the spotlight on modern art’s oft-unheralded black models, affording these previously anonymous sitters a semblance of agency by (temporarily) renaming classic canvases in honor of their newly identified subjects. Titled "Black Models: From Géricault to Matisse," the show presents works including Édouard Manet’s “Laure,” a subversive nude formerly dubbed “Olympia,” and Marie-Guillemine Benoist’s “Portrait of Madeleine,” an allegorical painting previously known by the generic name “Portrait of a Black Woman.”

As Jasmine Weber reports for Hyperallergic, the Parisian presentation is an expanded version of "Posing Modernity: The Black Model from Manet and Matisse to Today," an exhibition that premiered at Columbia University’s Wallach Art Gallery last October. Based on then-graduate student Denise Murrell’s thesis of the same title—born, in turn, out of Murrell’s frustration over the lack of scholarship surrounding black women in the art canon—the New York City show brought together more than 100 paintings, sculptures, photographs and sketches in a study of overlooked black models.

The revamped show has a similar focus, the Washington Post’s James McAuley observes, but carries a different tenor in France, where he says “the state is officially blind to race, both as statistical category and as lived experience.” Drawing on selections from the show’s original iteration, as well as a rich array of related works held in the Musée d’Orsay’s permanent collection, "Black Models" strives to not only shift the conversation toward sitters whose stories are only now being told, but to interrogate the country’s own role in the global slave trade.

Slavery was abolished in the French colonies in 1794 but reinstated under Napoleon Bonaparte in 1802. It took another 44 years for the practice to be permanently banned. According to the BBC’s Cath Pound, black and mixed-heritage individuals living in Paris during this era were best represented by art, as public records failed to specify race. A Haitian man named Joseph, for example, was reportedly Théodore Géricault’s favorite model, appearing in the artist’s “The Raft of the Medusa” and, following Géricault’s death in 1824, becoming a model at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts.

Laure, the maid depicted at the sidelines of Manet’s provocative 1863 “Olympia,” also appears in two separate scenes titled “Children in the Tuileries Gardens” and “La Négresse (Portrait of Laure).” Writing for The New York Times, Roberta Smith notes that Laure made a clear impression on Manet, who described her as a “very beautiful black woman” and recorded her address in a studio notebook. Manet painted Laure in a manner that revealed her class, status and country of origin without reducing her to the “bare-breasted” black subjects of fantastical harem scenes, but as Murrell tells the BBC’s Pound, the “free, wage-earning woman” seen in these works remained limited by a society still “essentially racist and sexist."

The relatively respectful representations of black models seen in these works are, unfortunately, the exception rather than the norm. Speaking with Agence France-Presse, Murrell says that black individuals played a major role in the development of modern art, but their contributions were eclipsed by the use of reductive, “unnecessary racial references” such as “negress” and “mulatresse,” a derogatory term for those of mixed-race descent.

“Art history … left them out,” Murrell explains to BBC News. “[These labels have] contributed to the construction of these figures as racial types as opposed to the individuals they were.”

Benoist’s “Portrait of a Black Woman,” also known as “Portrait of a Negress” but now renamed “Portrait of Madeleine,” exemplifies the tension between treating black subjects as individuals versus racist caricatures. The Post’s McAuley points out that the canvas, painted in the brief period between slavery’s abolition and reinstatement under Napoleon, is often viewed allegorically. Featuring a bare-breasted black woman in a tri-color dress reminiscent of both Liberty and the French flag, the work seems to refer to the recently resolved French Revolution or the impending return of slavery—perhaps both.

At the Musée d’Orsay’s new exhibition, however, the portrait transforms into a rendering of a specific individual: Madeleine, an emancipated slave from Guadeloupe who was hired as a domestic servant by Benoist’s brother-in-law. “For more than 200 years there has never been an investigation to discover who she was,” Murrell tells AFP, even though this information “was recorded at the time.”

Although the central focus of "Black Models" is the crop of retitled portraits, the BBC’s Pound writes that the show also emphasizes black and mixed-race figures who were well-known by their contemporaries. Miss Lala, a mixed-race circus artist whose act found her suspended from the ceiling by a rope clenched in her teeth, is immortalized in an 1879 pastel by Edgar Degas, while Jeanne Duval, a mixed-race actress and singer who was poet Charles Baudelaire’s mistress, appears in an 1862 Manet painting. Moving to photography, the Musée d’Orsay highlights Nadar’s studio portrait of Alexandre Dumas, author of French classic The Three Musketeers and the paternal grandson of a Haitian slave.

If none of these names sound familiar, a large-scale neon installation on view in the Paris institution’s atrium is sure to help cement them in your memory. The work, called “Some Black Parisians,” is the brainchild of American artist Glenn Ligon and consists of 12 giant, glowing names inscribed on two towers. As artnet News’ Naomi Rea reports, some of the 12 refer to famous figures such as Dumas and performer Josephine Baker. Two recognize Laure and Jacob, the still under-studied muses of Manet and Géricault. But perhaps most striking is a Latin phrase written alongside the 12 names: Proclaiming “Nom inconnu,” or “name unknown,” the words serve as a stark reminder of all the black models whose names—and contributions—remain lost to history.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)