Mexico Establishes Largest Marine Protected Area in North America

The nation will fully protect 57,000 square miles around the Revillagigedo Islands from fishing and resource extraction

Today, Mexico's president, Enrique Peña Nieto, signed a decree creating a massive marine reserve, spanning 57,000 square miles around the four Revillagigedo Islands—a volcanic archipelago 240 miles southwest of the Baja Peninsula. The reserve is the largest marine protected area yet created in North America.

Though the islands have been a biosphere reserve for over 20 years, the new status greatly expands and fully protects the region from fishing, mining and other extractive industries. The Revillagigedo Islands are currently uninhabited, and the new status will prevent the development of hotels or other tourism infrastructure. Commercial dive operators, however, will still be permitted to run trips to the area.

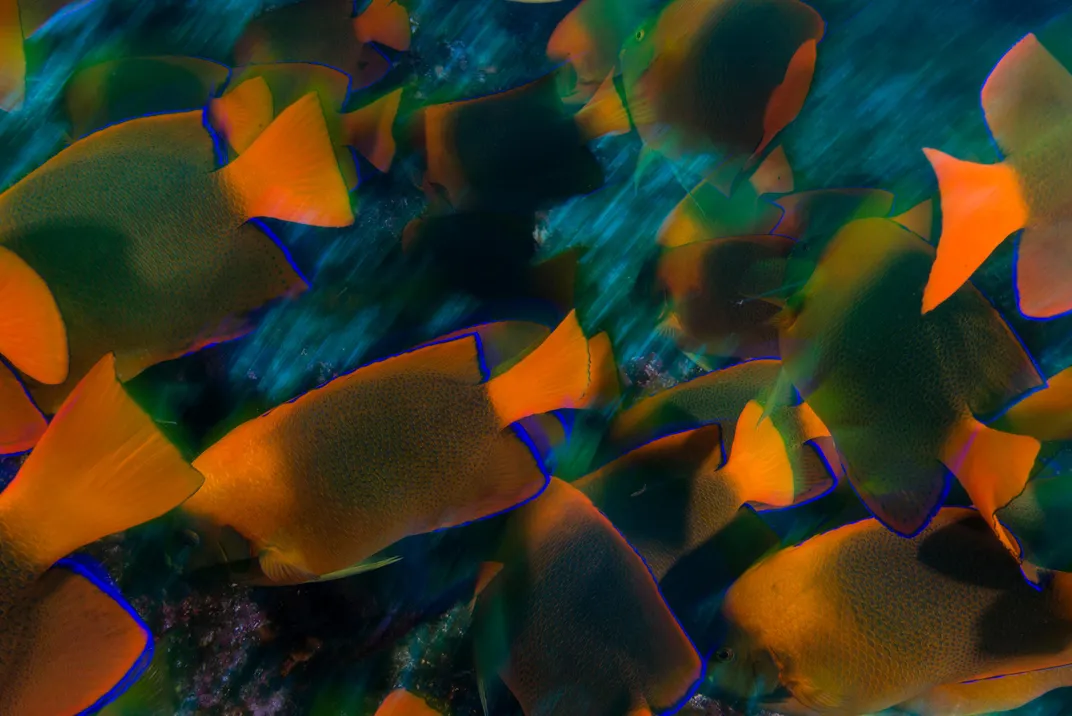

While the Revillagigedo Islands themselves support many species of endangered birds and plants, the declaration is aimed at preserving the waters offshore, which support 366 species of fish, including 26 endemic to the islands, as well as 37 species of rays and sharks, including the behemoth whale sharks. The islands also function as calving grounds for humpback whales and support coral gardens and a range of other relatively pristine marine ecosystems.

“It’s an important place biologically for megafauna, kind of superhighway, if you will, for sharks, manta rays, whales and turtles,” Matt Rand, director of the Pew Bertarelli Ocean Legacy Project, which worked with Mexico in support of the reserve, tells Smithsonian.com. “It’s a pretty biologically spectacular location.”

Fishermen, however, have expressed some opposition to the project, report Brian Clark Howard and Michael Greshko for National Geographic. But as ocean conservationist Enric Sala tells National Geographic, the reserve impacts only a small fraction of fishing regions—just seven percent of the waters currently fished by the Mexican tuna fleet.

Sala, who is a National Geographic Explorer-in-Residence, surveyed the region in 2016, finding that the reserve could actually improve fishing in the region. Increased population of fish in the reserve would potentially “spill over” into areas outside the Revillagigedos. He tells National Geographic that a similar process happened in 1998 around the Galapagos.

The idea of expanding the sanctuary zone around the Revillagigedos has been kicked around for years. But it took a push by Pew working with local conservation groups Beta Diversdad, CODEMAR and the Mexican Ministry of the Environment to move the project forward.

Rand says the reserve has all of the elements identified to make a great ocean sanctuary. “There was a key study in Nature three years ago that found the five key elements to successful marine reserves are that they are large, fully protected, old, well-enforced and isolated,” Rand says. “This marine reserve will have all of that except age, and that will come.”

Of course, a successful reserve is only as good as its enforcement, and Rand says he currently doesn’t have many details on how the Mexican government will implement the no-fishing rules.

In recent years, however, technology has greatly improved and with it the ability for conservationists to police marine reserves, he says. For instance, Oceana’s Global Fishing Watch platform uses satellite signals from vessels on the ocean to track the fishing fleet around the world and the conservation organization OceanMind uses satellites and other technology to monitor marine protected areas as well.

The new reserve is part of a wave of recent ocean preserves. In 2016 then-President Barack Obama expanded the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument in Hawaii, which now clocks in at some 582,500 square miles. This same year, President Obama also established the 4,913-square-mile Northeast Canyons and Seamounts Marine National Monument off New England shores. Also that year, an international body declared a 600,000-square-mile reserve in Antarctica’s Ross Sea. In 2015, Great Britain declared the 322,000 square miles around the Pitcairn Islands a fully protected reserve. In October, Chile created two new reserves the size of France.

Rand tells Smithsonian.com that these recently established reserves, as well as proposed projects in places like the South Sandwich Islands, are an encouraging sign. The current scientific consensus is that at least 30 percent of the ocean needs to be fully protected to conserve biodiversity and healthy ecosystems. Less than 10 percent is currently protected, says Rand, and less than two percent is highly protected.

“We have a long way to go," he says. "But there’s been incredible growth in the concept of large-scale marine protected areas. It’s almost becoming a race. Hopefully it’s starting to snowball.”