Exceptional Fossils Show Ancient Winged Mammals May Have Glided Above the Dinosaurs

The discovery of two flying squirrel-like fossils suggest mammal diversity began earlier than previously thought

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d0/26/d026a24a-02b8-4b14-9cd7-b912c68c3558/01-maiopatagium-fossiladapt9451.jpg)

Gliding mammals, like flying squirrels, sugar gliders and colugos are pretty impressive creatures, with some capable of flying up to 300 feet in a single jump between trees. While gliding might seem like a novelty among modern mammals, as Shaena Montanari at National Geographic reports, two new fossils found in China suggest that the mammalian ancestors likely figured out how to glide during the age of the dinosaurs, 160 million years ago.

The two well-preserved fossils were discovered in the Tiaojishan Formation in Hebei Province, China in sediments from an ancient lake. As Montanari reports, the fossils include well-preserved bones and teeth as well as imprints of the skin flaps the creatures used to glide. The research was published this week in two papers in the journal Nature.

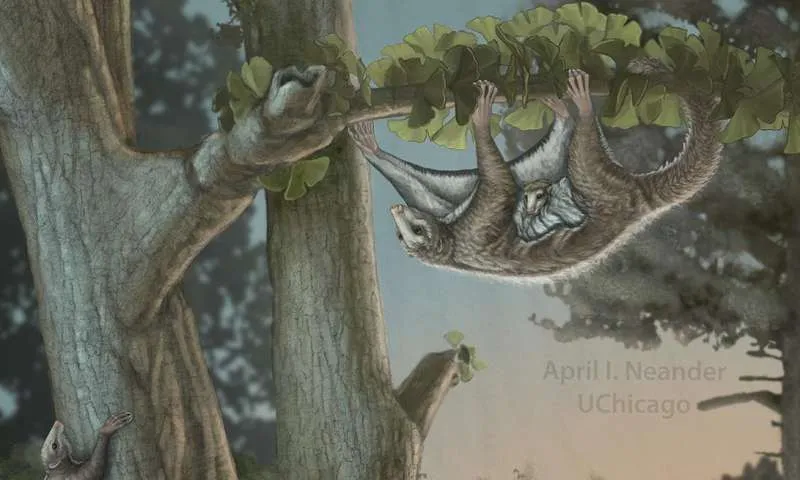

One specimen, Maiopatagium furculiferum, was about the size of a squirrel and had simple teeth like modern species that gnaw on soft fruit. The other species, Vilevolodon diplomyos, was closer in size to a mouse and had ridged molars, similar to modern seed-eating species, though, according to a press release, both species lived at a time before the dawn of flowering plants and likely specialized in eating parts of the ferns, conifers and gingkoes that dominated the Jurassic.

Ten other gliding mammals from the Jurassic era have been previously found in recent years, suggesting that the strategy of gliding and the ecological niches it opened up was well-established during the period. However, these two new specimens are the oldest gliders discovered so far.

As Carl Zimmer at The New York Times reports, in the past, paleontologists believed that proto-mammals during the Mesozoic Era which lasted 252 to 66 million years ago were not very diverse. Most, they thought, were little nocturnal insect-eaters scurrying around after the dinosaurs went to bed. But in the last decade, researchers have found that’s not true.

Besides the gliding animals they’ve also discovered a range of species, Zimmer reports. There were otter-like swimmers, raccoon-like critters that predated on eggs, and even aardvark-like creatures that chowed down on insect nests. “We consistently find with every new fossil that the earliest mammals were just as diverse in both feeding and locomotor adaptations as modern mammals," Luo says in a press release. “The groundwork for mammalian success today appears to have been laid long ago.”

Both of the new gliders are haramiyidans, which are an extinct branch of pre-mammals. As Zimmer reports, in many ways they are very different from mammals of today. They likely laid eggs and did not have the unique bones mammals use to hear. At the same time they look similar to the furry, warm-blooded gliders we have today.

"I was stunned when first seeing these specimens — they looked as if they just fell flat into a shallow lake, with limbs and their gliding membranes spread perfectly out, fossilized for eternity,” Luo tells Laura Geggel at LiveScience. “They are almost like modern mammal gliders!”

The ancient gliders died out well before the dawn of modern mammals. According to the press release, the fossils are a great example of convergent evolution, in which unrelated species develop similar evolutionary strategies. Two branches of modern mammals developed gliding at least 100 million years later, leading to today's marsupial sugar gliders and flying squirrels.