Hurricane Dorian Batters the Bahamas Before Barreling Along the U.S. Coast

The storm caused historic damage in the Caribbean islands, where it hovered for some 48 hours

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a9/d9/a9d973cd-1d94-429f-8b08-a47f6f34b8c5/hurricane.jpg)

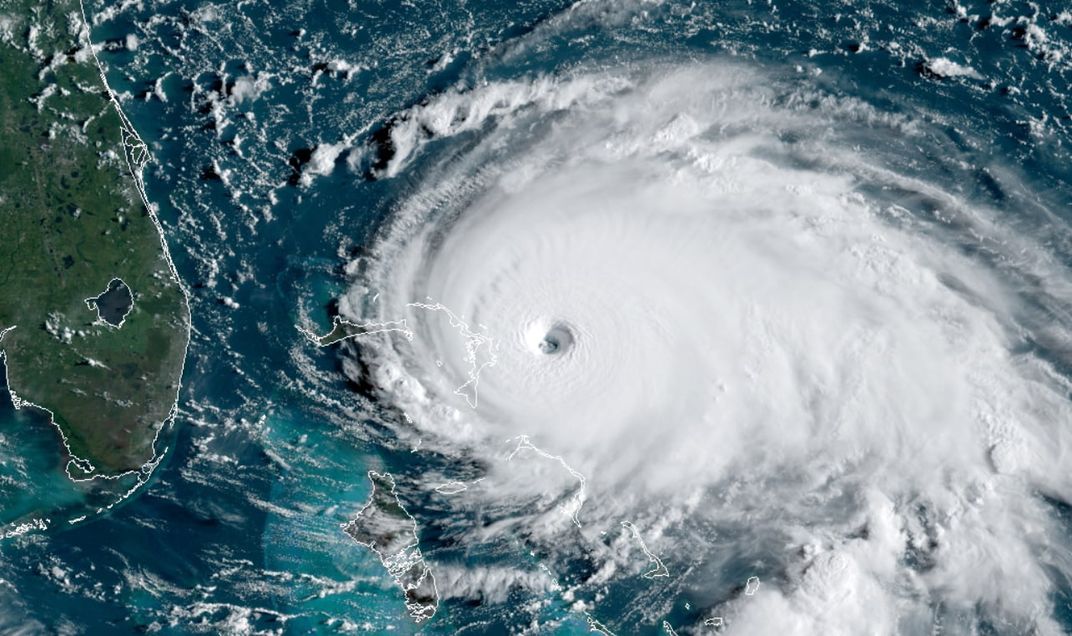

Hurricane Dorian is the strongest storm to ever hit the Bahamas. The storm holds the title for fastest winds this far north in the Atlantic Ocean east of Florida with sustained max speeds of 185 miles per hour. Dorian went from a Category 2 storm to a Category 5 storm in just two days, propelled by a process called rapid intensification, before dropping back to a Category 2 storm on Tuesday afternoon. Its low pressure of 911 millibars tops Hurricane Andrew’s pressure in 1992, and it’s been maintaining a shockingly uniform shape as satellite images have shown, report the Washington Post’s Jason Samenow and Ian Livingston.

In a press conference Tuesday night, Bahamian Prime Minister Hubert Minnis said Dorian is "the greatest national crisis in our country's history."

The hurricane remained a Category 5 storm after it made landfall in the Bahamas and maintained its strength as it slowly crept across the islands. The now-Category 2 storm scraped the Florida and Georgia coasts late Tuesday night, but landfall is still a distinct possibility in the Carolinas from Thursday through Friday morning.

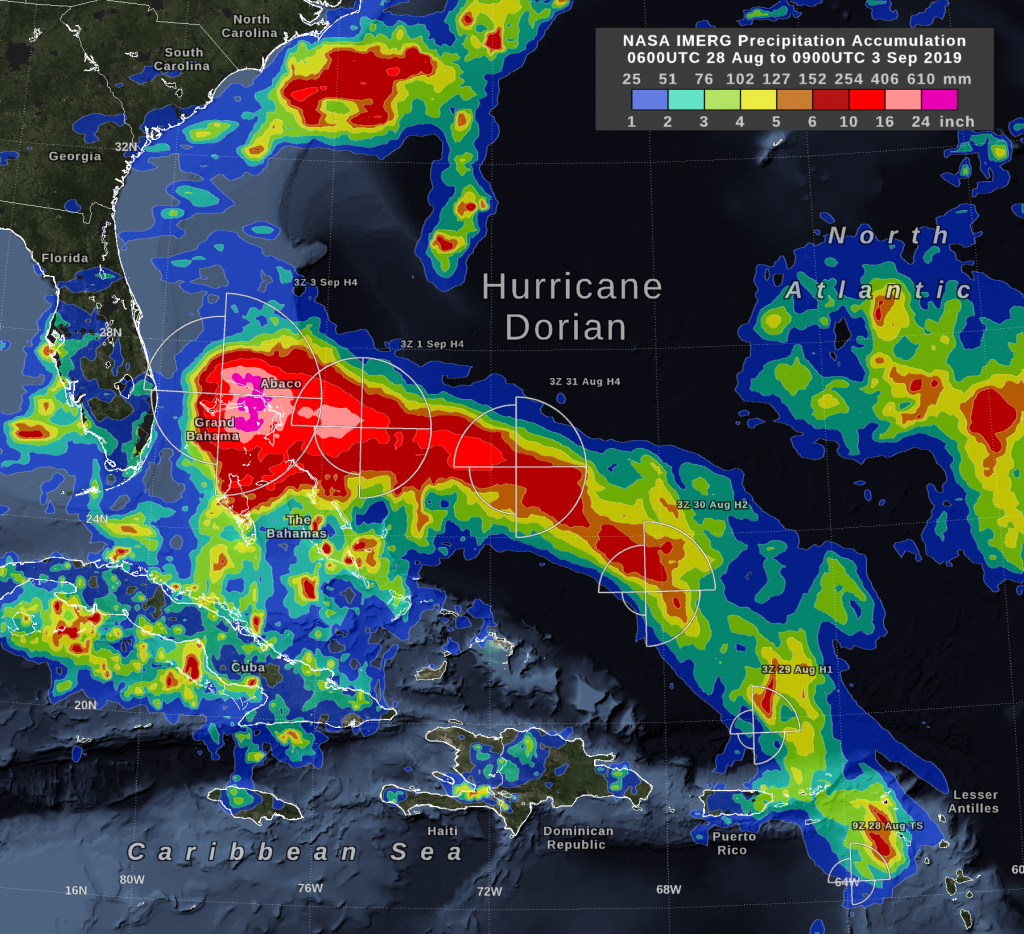

Hurricane Dorian struck land in Elbow Cay, Abaco Islands, at 12:40 p.m. ET on Sunday afternoon. It slunk across the Abaco Islands to Grand Bahama Island where the eye of the storm stayed parked for 48 hours into Tuesday afternoon, according to NOAA. The storm moved only 30 miles in 30 hours, report CNN’s Patrick Oppmann, Jason Hanna and Christina Maxouris.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/81/68/8168959e-7fa4-4c29-b574-7582d0d6a136/190904085957-nick-hague-dorian-eye-exlarge-169.jpg)

It was a storm unlike anything the islands had ever experienced. Hurricane conditions remained in the Bahamas through Tuesday night. Winds ravaged the area, shredding buildings and snapping trees like twigs. Flooding caused by more than 30 inches of rainfall and storm surges as high as 23 feet left many stranded on top of whatever structures remained standing.

On the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale, damage increases exponentially. According to a National Weather Service chart of damage potential from hurricanes, a Category 5 storm with 185 mph winds can be 1,371 times more damaging than a Category 1 storm with 75 mph winds.

Nearly 400,000 people live in the Bahamas, and areas of top concern include parts of the Abaco Islands where Haitian migrants live in shantytowns, as Kevin Harris, director general of the Bahamas Information Center, tells the New York Times’ Patricia Mazzei, Frances Robles and Nicholas Bogel-Burroughs. The Red Cross reports that nearly half of the homes, or 13,000, in Abaco and Grand Bahama Island are damaged or destroyed, according to the Associated Press. An estimated 62,000 people are without clean water, and the Grand Bahama International Airport now resembles a lake.

“We are already hearing from residents that whole towns have been wiped out and devastated,” Harris tells the Times. “This is going to be a big search-and-rescue and rebuilding effort. I don’t think we have seen anything as bad as this. This one is for the history books.”

Volunteers and survivors of the storm are leading current search-and-rescue efforts. Seven are confirmed dead, but government officials expect that total to rise. When the Bahamian government is finally able to fully assess the situation, the U.S. Department of Defense has authorized 5,000 Coastguardsmen, 50 to 60 highwater vehicles, and 40 to 50 helicopter crews to assist with rescue and recovery efforts, reports Barbara Starr at CNN. Three different hospital ships are also within a few days sailing of the island, should they be needed.

By Tuesday afternoon, the storm was reduced to a Category 2 hurricane with 110 mph winds as it headed northwest toward Florida. It is, however, expected to gain speed and strength along its path.

The storm is so large that hurricane-strength winds stretch 60 miles out from the storm center, and tropical storm-strength winds stretch out 175 miles, according to CBS News. Because of this, Floridians and Georgians were spared the brunt of the storms power, but still experienced high winds and heavy rainfall on Tuesday evening. Thousands in Florida were left without power by Wednesday morning.

The storm’s effects are worsened by the fact that Florida’s King Tides—highest of high tides—are at their peak this week, reports CNN’s A.J. Willingham. This round of King Tides is intensified by two factors: The close proximity of the moon and warmer water temperatures that are common during autumnal King Tides.

"The sun has baked the ocean all summer in the tropics and the ocean literally expands," explains CNN meteorologist Brandon Miller. Because warm water feeds hurricanes, this could mean significantly more intense storm surges, or rapid flooding, on Florida’s coast.

By Wednesday morning, however, Dorian shifted further westward on its route north, bringing worsening tropical storm conditions to the Georgia and South Carolina coasts. As it continues on that path, it could make landfall in North Carolina or southeastern Virginia later this week, according to the Weather Channel.

Last year, Hurricane Florence hit just north of Wilmington, North Carolina, as a Category 1 hurricane. Significant storm surges caused flooding in some cities as the storm slowed moving inland. Hurricane Dorian is currently headed for the same region. Historically, the Carolinas have dredged deeper in their ports to accommodate larger container ships, expanding their tidal range in certain areas and priming inland areas for devastating storm surges, Jim Morrison reported for Smithsonian.com last year. (Charleston, South Carolina, for example, has ports dredged up to 50 feet deeper than natural depths. Millions in the state have been under evacuation orders this week pending the arrival of Hurricane Dorian.)

In our warming world, sea level rise is one of the many factors contributing to a future with more devastating hurricanes. “By 2100, storm surges will happen on top of an additional 8 inches to 6.6 feet of global sea level rise,” according to NOAA’s Climate Toolkit. Because water weighs 1,700 pounds per cubic yard, bigger waves moving at 10 to 15 mph can steamroll structures that aren’t built to last.

Higher water temperatures mean wetter and slower moving storms, too, according to a 2018 study produced by the National Center for Atmospheric Research. 2017’s Hurricane Harvey produced four feet of rain alone in some areas. And Hurricane Dorian was particularly slow moving in the Bahamas, inching along at just at one mile per hour. Climate change won’t necessarily yield more storms, but rather, stronger storms.

Does this mean we need to add Category 6 to the hurricane scale, or revise how we categorize hurricanes? It’s complicated. The Saffir-Simpson scale is based on wind speed, which isn’t exactly a holistic view of how hurricanes cause devastation. A sixth category would hypothetically start at 182 mph, explains meteorologist Ryan Moue on Twitter. And experts do expect storms to get more powerful, some forecasting 200 mph storms in the next few decades, report the Miami Herald’s Alex Harris, Douglas Hanks and Alex Daughtery. Hurricane Dorian’s sustained 185 mph wind speeds place it alongside several storms as the second-strongest in the Atlantic, just after the 1980’s Hurricane Allen, which hit 190.

Gabriel Vecchi, a geoscientist at Princeton University, tells the New York Times’ John Schwartz that there have “been strong storms in the past,” and it would be inaccurate to attribute every intense storm to climate change. That’s not what experts mean.

Rather, Vecchi says, “[Hurricane Dorian] looks like what we’re going to have more of in the future.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/rachael.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/rachael.png)