Mansion of Woman Falsely Blamed for 1871 Great Chicago Fire Is Up for Sale

Mrs. O’Leary’s son built the house for her after the disaster. Now, the property is on the market—and it comes with a fire hydrant

:focal(596x473:597x474)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/15/fb/15fbd25e-4add-4989-a768-6dda8e278aab/house_front.jpg)

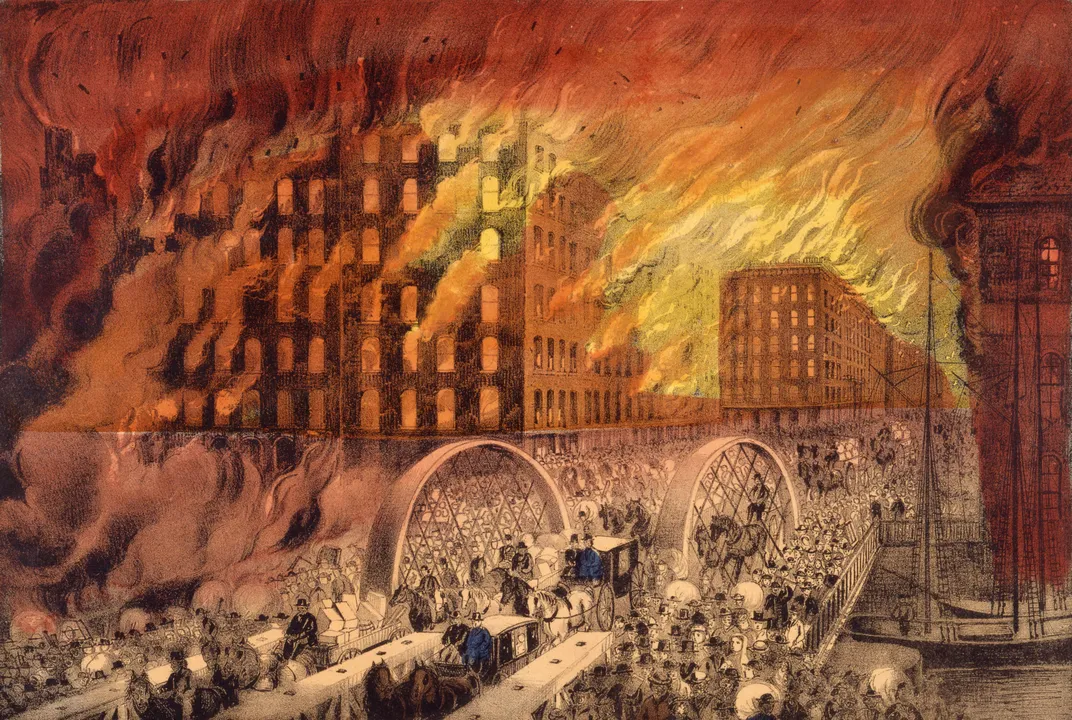

After sparking in Chicago’s southwest side on October 8, 1871, the Great Chicago Fire swept through the city for more than 24 hours. The blaze razed a huge swath of the Illinois metropolis, killing an estimated 300 people and leaving another 100,000 homeless.

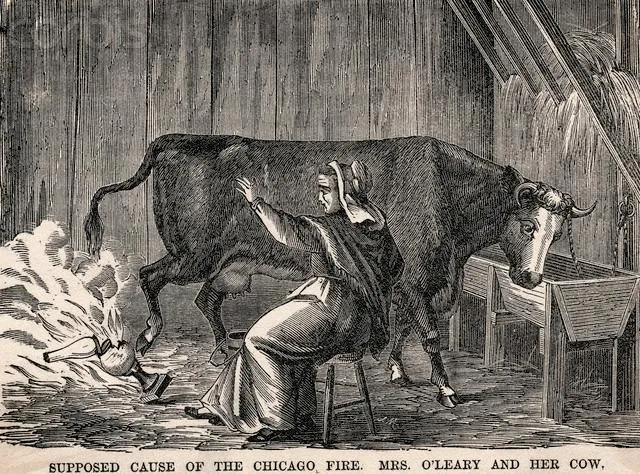

In the aftermath of the fire, reporters singled out 44-year-old Irish immigrant Catherine “Cate” O’Leary as a scapegoat. O’Leary’s unruly cow, they claimed, had kicked over a lantern in the family’s DeKoven Street barn and sparked the inferno. Though the story was a lie (40 years after the fact, journalist Michael Ahern admitted to making the tale up, according to the Chicago Tribune), it nevertheless took hold. For the rest of her life—and beyond—O’Leary’s name would be tied to the infamous 1871 disaster.

Nearly 150 years later, the home where O’Leary lived later in life is back on the market. As Jamie Nesbitt Golden reports for Block Club Chicago, O’Leary’s son, notorious gambling boss and saloon owner James “Big Jim” O’Leary, built the mansion at 726 W. Garfield Blvd. for his mother around 1890. Following her death in 1895, James lived in the Englewood neighborhood home until his own death in 1925.

Ironically, O’Leary’s mansion may be the only house in the city to have its own dedicated fire hydrant.

“James was very afraid of his property burning down, so he had a fire hydrant installed directly behind his property, in the alley,” listing agent Jose Villaseñor told Realtor.com’s Tiffani Sherman last November.

Speaking with Block Club, Villaseñor notes that the 12-bedroom, 5.5-bath property has two large vaults on its first floor and in the basement. Blueprints indicate that a secret tunnel once connected the mansion to a home next door—perhaps a remnant of a Prohibition-era getaway, the realtor suggests.

Though the property will require refurbishment, “[i]t’s truly a beautiful place, from the hardwood floors [to the coffered ceilings, the wainscoting,” says Villaseñor to Block Club. “… [I]t’s like going back in time.”

The property, which includes a two-story coach house and the three-story brownstone, is listed at $535,770.

Crain’s Chicago Business reports that the house was previously listed for sale in 2007. Villaseñor tells Block Club that the current owner is ready to leave the mansion after owning it for 30 years.

Ward Miller, president of Preservation Chicago, tells Block Club that he hopes the new owner will consider pursuing historic landmark status for the mansion, whose interior is in need of significant upgrades. A buyer interested in converting the space into smaller condominiums may be able to do so, but this work “would have to be done carefully, with certain … rooms kept intact,” he adds.

Buildings tied to history hold “wonderful stories that are sometimes overlooked,” says Miller to Block Club. “We would like to see the city be more proactive in protecting these buildings and promoting them.”

Mrs. O’Leary, for her part, bore the weight of the historic fire for the rest of her life, as historian Karen Abbott wrote for Smithsonian magazine in 2012. Newspapers and members of the public encouraged vitriolic depictions of O’Leary that played into ethnic stereotypes, prevailing nativist fears and anti-Irish sentiment by depicting her as “shiftless” or a “drunken old hag.”

The woman herself shunned press coverage. But in 1894, the year before her death, O’Leary’s physician offered a telling comment to the press: “That she is regarded as the cause, even accidentally, of the Great Chicago Fire is the grief of her life.”

The doctor added that O’Leary refused reporters the chance to reproduce an image of her face, lest she become the subject of further mockery.

“She admits no reporters to her presence, and she is determined that whatever ridicule history may heap on her it will have to do it without the aid of her likeness,” he said. “… No cartoon will ever make any sport of her features. She has not a likeness in the world and will never have one.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)