Fallen Boulder at the Grand Canyon Reveals Prehistoric Reptile Footprints

313 million years ago, two reptilian creatures crept over this boulder’s surface

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/cf/59/cf59bef6-1da2-4890-a468-ab23425e9668/cliff_image.jpg)

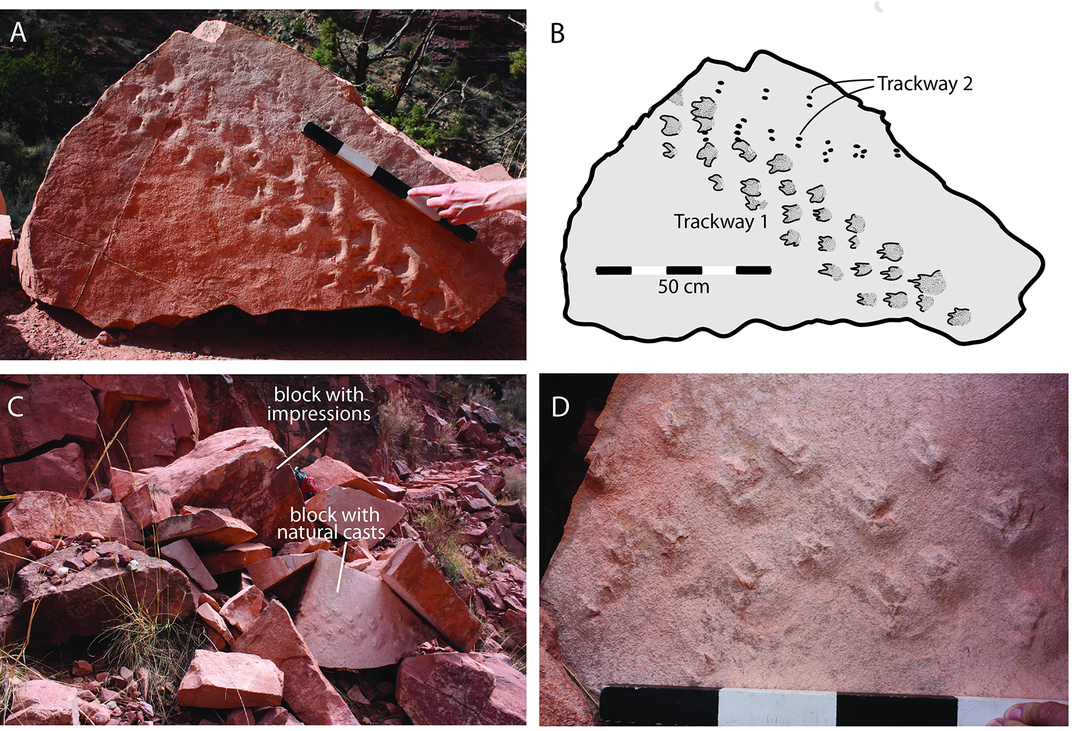

Geologist Allan Krill was hiking along the Grand Canyon National Park’s Bright Angel Trail with a group of students in 2016 when he spotted it: a fallen boulder lying just off the side of the trail, with curious markings that resembled footprints. Krill, who was visiting the University of Nevada, Las Vegas (UNLV) from Norway, sent photos of his find to an old friend and colleague, Stephen Rowland, a UNLV paleontologist.

Krill’s discovery turned out to be ancient fossilized footprints. The find was initially announced at the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology’s Annual Meeting in 2018. Now, in a new paper published last week in PLOS One, Rowland estimates that the imprints could be up to about 313 million years old, making them the oldest vertebrate fossil tracks ever found in the Park, according to a National Park Service statement. Additionally, these footprints could be some of the earliest known evidence of a hard-shelled-egg-laying animal—what’s known as an amniote—in the world, reports Shaena Montanari for the Arizona Republic.

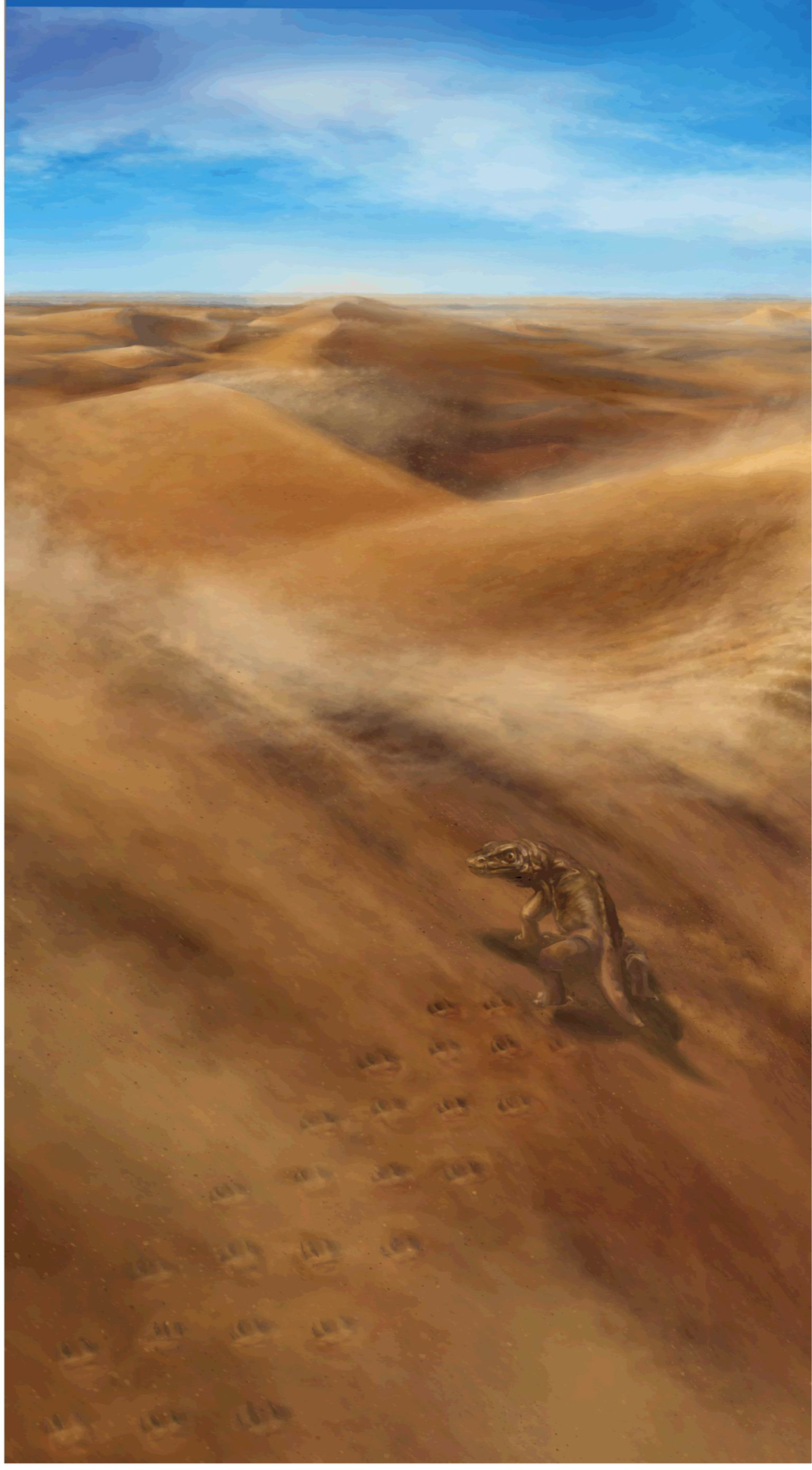

“These are by far the oldest vertebrate tracks in Grand Canyon, which is known for its abundant fossil tracks” says Rowland in the statement. What’s more, he adds, “they are among the oldest tracks on Earth of shelled-egg-laying animals, such as reptiles, and the earliest evidence of vertebrate animals walking in sand dunes.”

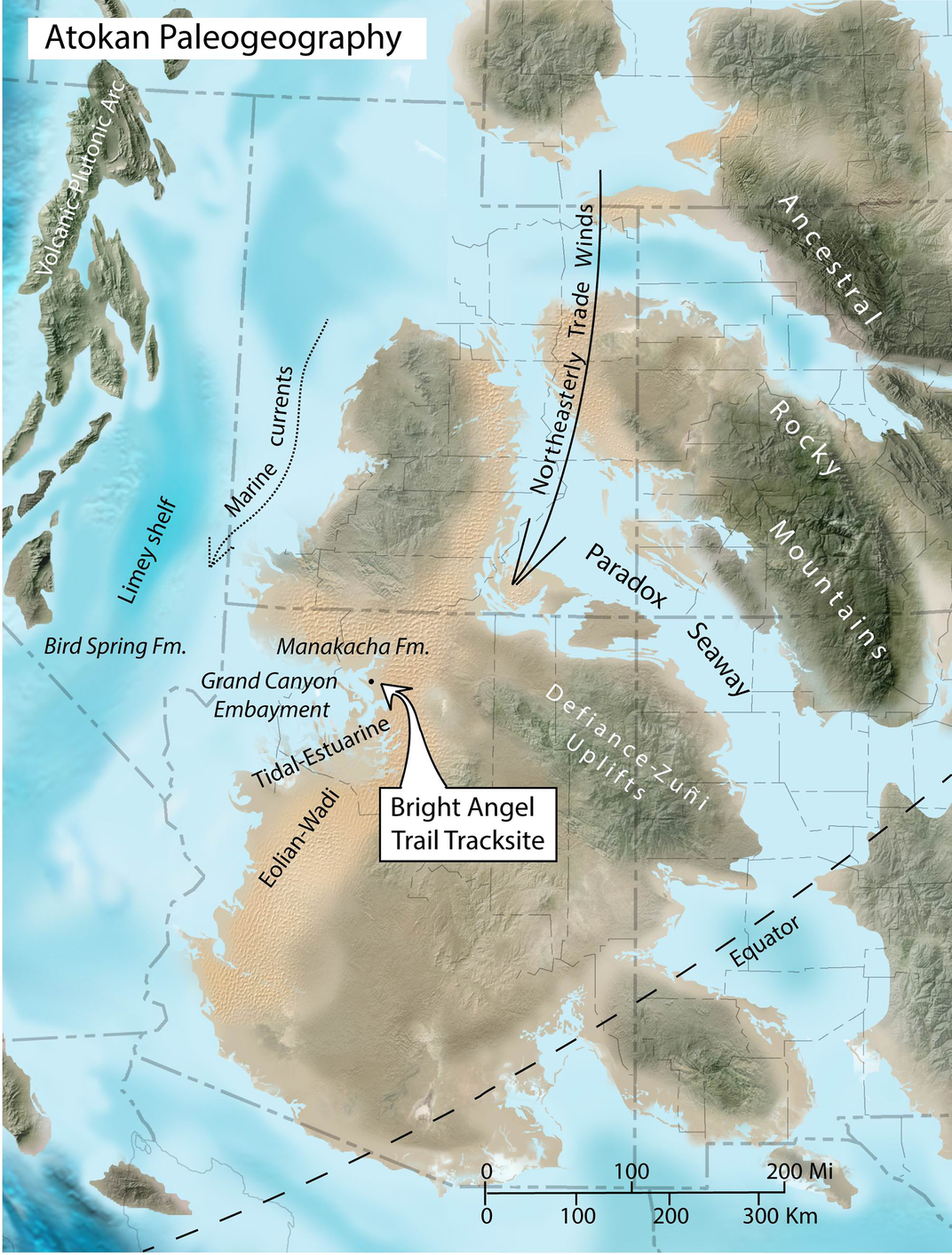

The track-bearing boulder weighs hundreds of pounds and had fallen from the Manakacha Formation, a large outcropping of sandstone that’s about 314 million years old, reports Harmeet Kaur for CNN. The tracks formed when they got wet and then were covered in sand, which preserved the markings for millions of years, reports George Dvorsky for Gizmodo.

Two sets of tracks made by ancient animals are clearly visible on its surface. By looking at previous studies of the age of the Formation, scientists were able to date the footprints to about 313 million years old, give or take half a million years, per the statement.

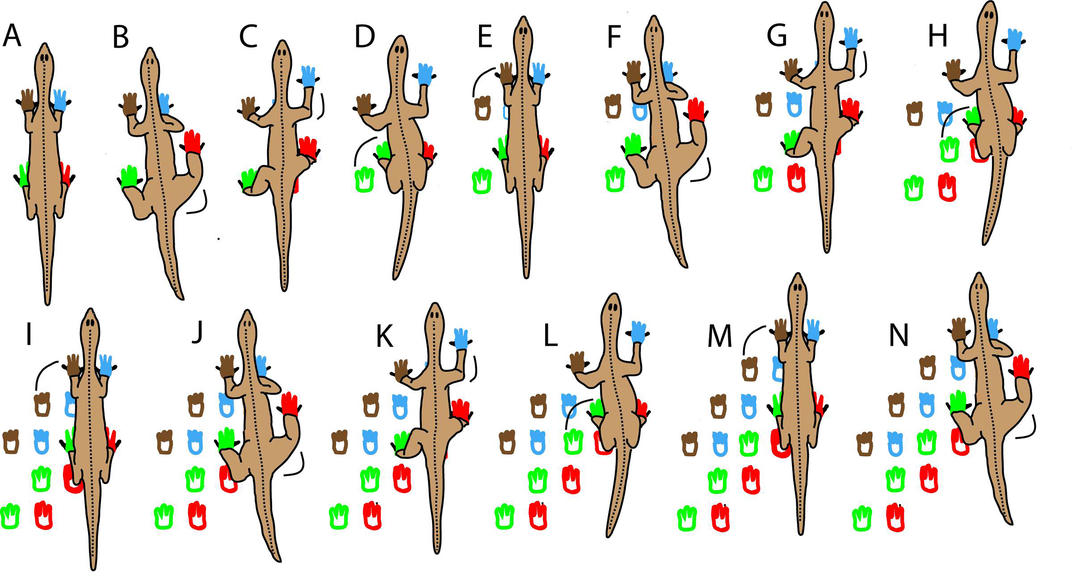

From what Rowland can make of the tracks, two separate reptilian animals crossed diagonally over this spot. One of the animals was about a foot long, and “uses a lateral sequence walk, where the left rear foot moves and then the left front, and then the right rear and the right front and so on,” Rowland explains to the Arizona Republic.

Scientists can’t be sure if the tracks come from two separate animals or the same animal at different times, reports Gizmodo. The second set of tracks are moving slightly faster than the first.

“Living species of tetrapods―dogs and cats, for example―routinely use a lateral-sequence gait when they walk slowly,” notes Rowland in the statement. “The Bright Angel Trail tracks document the use of this gait very early in the history of vertebrate animals. We previously had no information about that.”

Around 300 million years ago, what is now Arizona was a “coastal plain, with wind-blown dunes close to the equator,” notes Montanari. As Felicia Fonseca reports for the Associated Press, both the creatures and the sandstone formation predate dinosaurs.

As Rowland and co-authors write in the study, this find also represents the earliest evidence of amniotes living in sand dunes, predating other evidence by at least 8 million years.

Mark Nebel, the paleontology program manager at the Grand Canyon, tells the AP that some of the conclusions in Rowland’s study might prove controversial. “There’s a lot of disagreement in the scientific community about interpreting tracks, interpreting the age of rocks, especially interpreting what kind of animal made these tracks,” says Nebel.

Still, Nebel says that the find is an exciting one—especially because the boulder was lying in plain sight. “A lot of people walk by it and never see it,” says Nebel. “Scientists, we have trained eyes. Now that they know something’s there, it will draw more interest.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)