Explore the Seedy Reality of a London Long Gone

Charles Booth explored the poorest parts of England’s capital—and changed the way social scientists think about the world

Imagine a walk through London at the end of the 19th century. The city is alive with pedestrians and horses. It’s also crowded, dirty and filled with prostitution, drugs and crime. If you need an aid or two to jog your imagination, there’s no better place to look than the maps of Charles Booth, a social researcher and reformer whose exploration of the city’s seedier side helped change the way the world views social problems.

Booth’s work can now be found online thanks to Charles Booth’s London, a project dedicated to digitally documenting Booth’s groundbreaking work.

These days, Booth is viewed as a kind of godfather of statistics and sociology, a social reformer who recognized the need to face issues of poverty and crime head-on. Born to wealthy parents and a socially conscious family (his cousin was Beatrice Webb, who invented the term “collective bargaining), he became interested in the issues of urban life through charitable work. At the time, Victorian Britain was both wildly powerful and extremely poor. While working on how to allocate a relief fund in London, he realized that the census data he was using didn’t really show how poor London’s people were.

Then he read a book by Henry Hyndman, a Marxist who claimed that 25 percent of Londoners lived in poverty. That figure nagged at Booth, who felt it was much higher. But he didn’t have any data to prove his point. So he set out to get it himself. Over the course of nearly 20 years, he ran an inquiry into the condition of London’s workers that proved that in fact the number was more like 35 percent, called, appropriately, "Inquiry into the Life and Labour of the People in London."

At the time, the social sciences were in their infancy. Booth and his colleagues winged it, making up their own methodology as they went along. They gathered data by going into the hardscrabble streets of London themselves, even going along with police officers as they went about their business. Along the way, they gathered data on everything from prostitution to drug abuse to poverty and working conditions. The data Booth collected helped lead to Britain’s pension system and also influenced social reformers like Jane Addams and Florence Kelley, who used his methods to map out poverty around Hull House in Chicago.

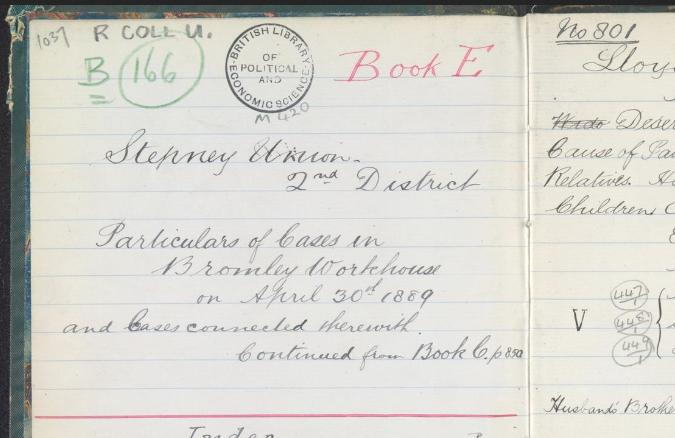

Social scientists still use some of Booth’s methods, and historians use his papers for a rare glimpse into what life really was like in turn-of-the-century London. A huge collection of Booth’s notebooks, maps, observations and other work is housed in the archive of the London School of Economics, and his "Inquiry into the Life and Labour of the People in London" has since been inscribed in Unesco's Memory of the World register.

Now, thanks to Charles Booth’s London, Booth's work is an easy read for anyone who wants to take a historical journey through a city whose seedier side was just as fascinating as its tonier pleasures. So take a virtual walk—and thank Booth for preserving information about London’s poor even as he tried to wipe out the conditions that made their lives so difficult.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erin.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erin.png)