Artist’s Quilts Pay Tribute to African-American Women

Artist Stephen Towns’ first museum exhibition showcases his painterly skill through traditional textile art

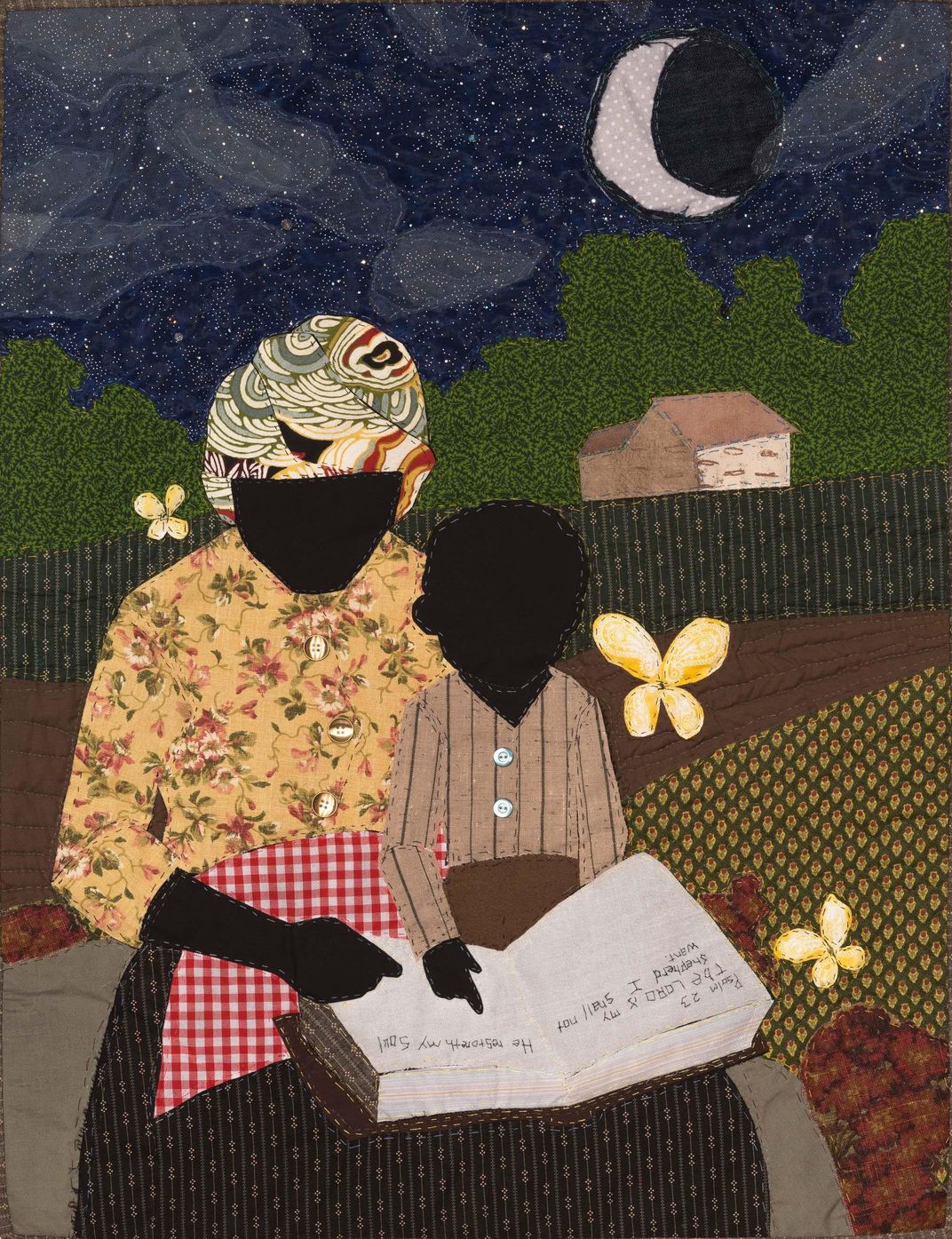

The quilts of Baltimore-based artist Stephen Towns resemble luminous paintings. In his first museum exhibition "Stephen Towns: Rumination and a Reckoning," the textile work sparkles and shimmers with glass beads, metallic thread, rich colors and translucent tulle. Through 10 quilts on display at the Baltimore Museum of Art (BMA), the visual artist tells the story of the slave rebellion Nat Turner led in August 1831 as well as the deeper story of how slavery and the labor of African-American women shaped America.

The centerpiece of exhibition, which was previewed in the New York Times, is a seven-and-a-half foot tall tapestry that shows a black woman nursing a white infant in front of the first official flag of the United States. The woman's profile is tall, her face bent towards the babe. The piece hangs suspended above a bed of earth piled on the gallery's wood floor, inches above but not touching. Towns calls the piece "Birth of a Nation."

The piece was the very first quilt that Towns worked on, he says in an interview with Los Angeles-based artist Mark Bradford, hosted in early March by the BMA. "I had tried various different ways to create the work, to create the message— the idea that black women have in many ways fed a nation," he says. "They are the very foundation of America. And through painting and drawing it just didn't work. So I decided to do quilting."

Towns' has a BFA in Studio Art from the University of South Carolina. The sensibilities he brings to his oil and acrylic paintings spills over into his textile art. While he says he picked up sewing from his mother and his sisters as a youngster, he actually turned to YouTube to teach himself quilting for this project.

"Quilting was the only way to get it done because it's an old tradition; it's a tradition that African-Americans have used for many years; it's a way of preserving memory through fabric," Towns tells Maura Callahan of Hyperallergic.

According to historian Pearlie Johnson an expert in African-American quilting history, since the 17th century, cultures in Ghana have been practicing strip textile weaving. While in West Africa, traditionally it was the men who were employed as weavers and commercial textile creators, in the United States, "gendered labor division" shifted that role to women on slave plantations.

"Quilt making had an important role in the lives of enslaved African-American women. It is possible that quilt making was one laborious activity that brought them a sense of personal accomplishment. Since then, African women passed... down these aesthetic traditions from one generation to the next generation of African-American women," Johnson writes in IRAAA+.

The familial connection to the women of Towns' family is manifested literally in "Birth of a Nation": The background flag's white stripes are cotton once worn by his mother, Patricia Towns, reports Mary Carole McCauley for The Baltimore Sun. The woman's headwrap and shirt are a pattern of green, red and blue fabric that Town's late sister, Mabel Ancrum, wore.

Towns recalls how his sister would clean wealthy people's offices and homes when he was young. He says the lack of respect she encountered made a deep impression on her. "Mabel would talk about the level of uncomfortableness she felt in that situation," he tells McCauley. "'Why do they treat me that way,' she would say, 'when my great-grandmother fed their grandfather?'"

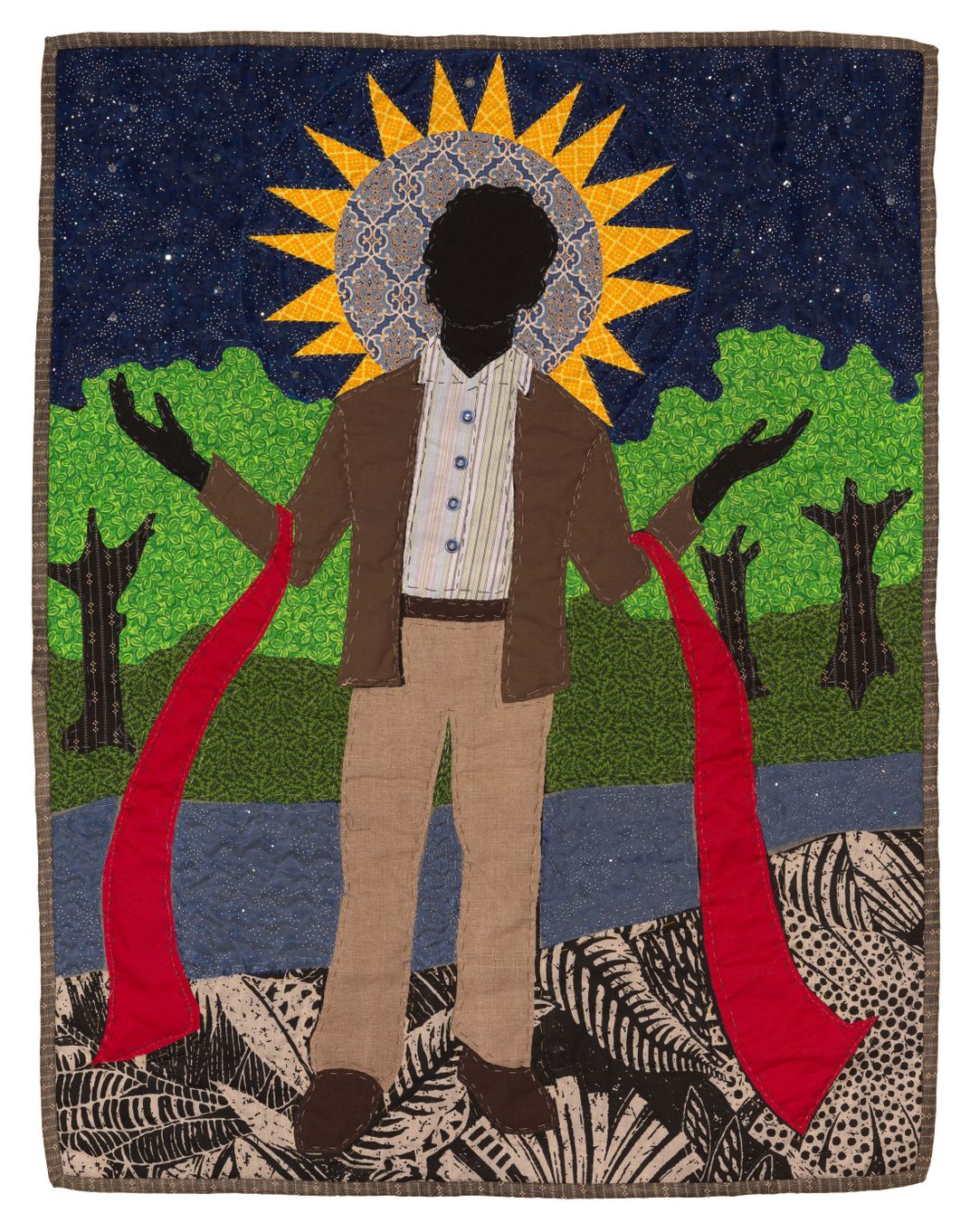

Other pieces in the exhibition depict events in the story of Nat Turner, who led a bloody rebellion of free and enslaved black people in 1831. Turner saw a solar eclipse in February of that year and took it as a sign from God. “And about this time I had a vision—and I saw white spirits and black spirits engaged in battle, and the sun was darkened,” Turner wrote in The Confessions of Nat Turner. Lauren LaRocca for Baltimore magazine notes that the sun, the moon and stars feature prominently in Towns' series inspired by Turner. In the piece "The Prophet," Turner's head is haloed by the sun, much like the moon during a solar eclipse.

For a previous exhibition at Goucher College, Towns painted portraits of formerly enslaved African-Americans who were hung after the Nat Turner rebellion. But when a female African-American security guard was offended by the paintings of men with nooses around their necks, McCauley reports that Towns voluntarily took down the work to respect her experience. He returned to the subject of the rebellion through quilting, using the medium to consciously engage in the narrative and craft of black women.

His work is personal, though none more so than "Birth of a Nation." As Towns tells McCauley, he made that quilt specifically as a tribute to his sister Mabel.

Stephen Towns: Rumination and a Reckoning is on display at the Baltimore Museum of Art now through September 2, 2018. Admission to the museum and the exhibition is free.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/18/b3/18b3a8b3-988e-4b92-bc0f-93a53d717e74/stephentowns_birthnation.jpg)