Dolphins May Be Able to Control Their Heart Rates

New study finds trained dolphins slow their hearts faster and more dramatically when instructed to perform long dives than short ones

:focal(356x239:357x240)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/09/03/09030894-ce12-476b-8f97-24daf23602d6/249074_web.jpg)

Along with other marine mammals and even humans, dolphins slow their heart rate before a dive as part of a suite of adaptations referred to as the mammalian diving reflex. But new research published last week in the journal Frontiers in Physiology shows that for bottlenose dolphins, slowing their heart rate isn’t just a reflex.

In a series of experiments, dolphins actually adjusted how much their heart rate slowed depending on how long they were going to dive, reports Ibrahim Sawal for New Scientist. Thumping out a slower rhythm of heartbeats while diving allows dolphins to conserve oxygen and manage decompression sickness, otherwise known as “the bends.”

The researchers behind the new paper trained three bottlenose dolphins to perform breath holds when shown particular symbols. One symbol meant the dolphin should start a short breath hold, and another symbol corresponded to a long breath hold.

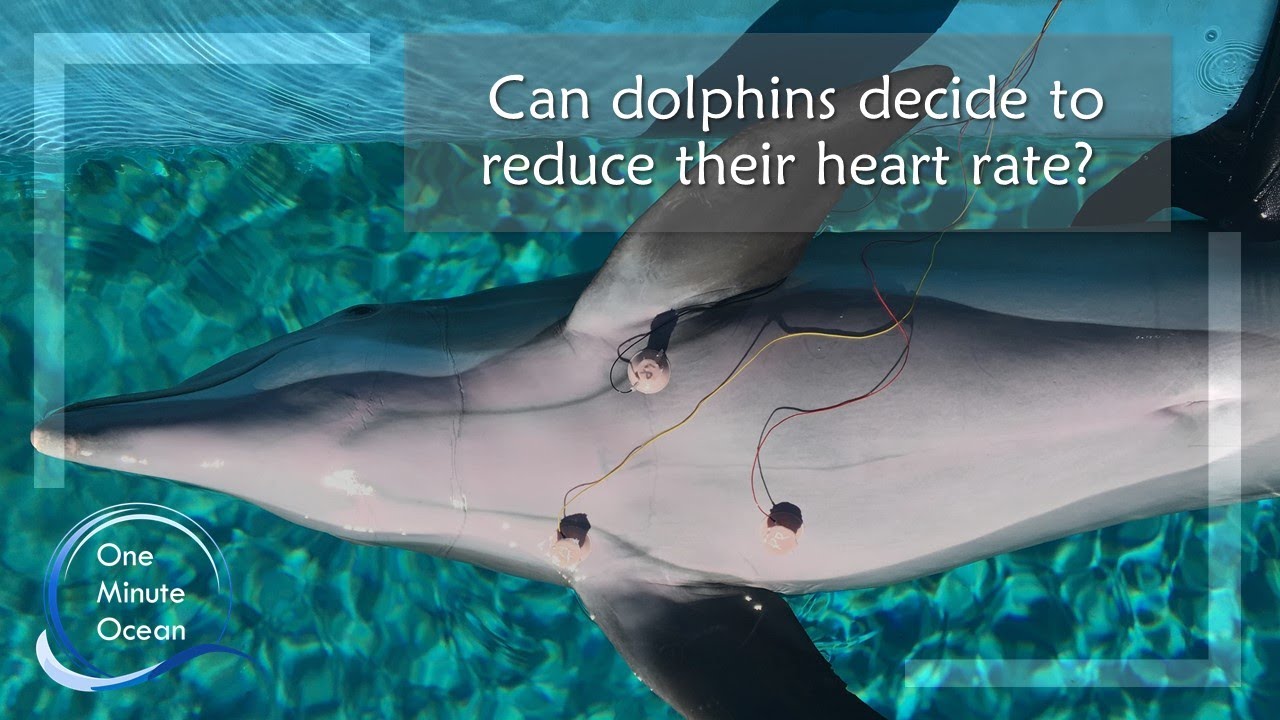

Electrocardiogram sensors attached to the dolphins monitored their heart rates, while another purpose-built device tracked the animals’ breathing, reports Brooks Hays for United Press International.

"When asked to hold their breath, their heart rates lowered before or immediately as they began the breath-hold. We also observed that the dolphins reduced their heart rates faster and further when preparing for the long breath-hold, compared to the other holds," says Andreas Fahlman, the lead author of the new paper and a marine biologist at Fundación Oceanogràfic in Spain, in a statement. The findings suggest that dolphins “have the capacity to vary their reduction in heart rate as much as you and I are able to reduce how fast we breathe,” he concludes.

Controlling how much their heart rates slow down for dives of varying durations and depths gives the dolphins the ability to customize the amount of oxygen their bodies consume. This skill can help maximize their time away from the surface or ensure their muscles are adequately supplied with oxygen during higher intensity swimming at shallower depths. But, Fahlman tells Tara Yarlagadda of the Inverse, it may also help the dolphins avoid the bends.

For air-breathing mammals, carrying lungs full of air into the ever-increasing water pressure of the deep carries risks beyond simply drowning. Though oxygen is what our bodies need to stay alive, Earth’s air is mostly made up of nitrogen. As a diving human, for example, stays underwater the oxygen in their lungs is used up but the nitrogen is not. During especially deep dives, the water pressure is so high that some of this nitrogen dissolves into the blood and tissues of the diver, because gases become increasingly soluble as pressure increases. As the diver surfaces and the water pressure decreases, this nitrogen comes back out of solution. If this decompression occurs too quickly the nitrogen forms bubbles that cause the uncomfortable and potentially fatal symptoms above.

So, when dolphins control their heart rate during dives, they may also be controlling the amount of nitrogen dissolving into their bodies. Specifically, Fahlman thinks this may be a sign of what prior research calls the “selective gas exchange hypothesis.”

"[The theory] proposed that by manipulating how much blood is directed to the lungs and to which region of the lung...[marine mammals] select which gas to exchange," Fahlman tells Inverse. "They can therefore still take up oxygen, remove carbon dioxide and avoid the exchange of nitrogen."

This study does not provide direct evidence of the selective gas exchange hypothesis, but showing that dolphins can actively modulate their heart rates does leave the door open to future investigations of whether they and other marine mammals might be capable of the other types of control over their physiology proposed by the hypothesis.

Fahlman tells New Scientist that while this study likely won’t help humans stay underwater longer, understanding how dolphins control their breathing may help us protect them. Fahlman says the intense blasts of undersea noise created by human activities at sea such as oil drilling and military exercises could interfere with dolphins’ ability to regulate their heart rates, and could put them at a greater risk of death.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/alex.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/alex.png)