Diamond Mines Are a Paleo-Climate Scientist’s Best Friend

A column of magma worked its way up from the mantle and drilled its way to the surface, bedazzling itself with diamonds that it picked up along the way

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20120921122008UNIS-AK.jpg)

A long time ago, in a place not that far away, there was a tree. It was just a normal tree, hanging out in the forest with its tree friends, not doing much except photosynthesizing, imbibing in groundwater and growing. Pretty typical tree activities.

Then the world exploded.

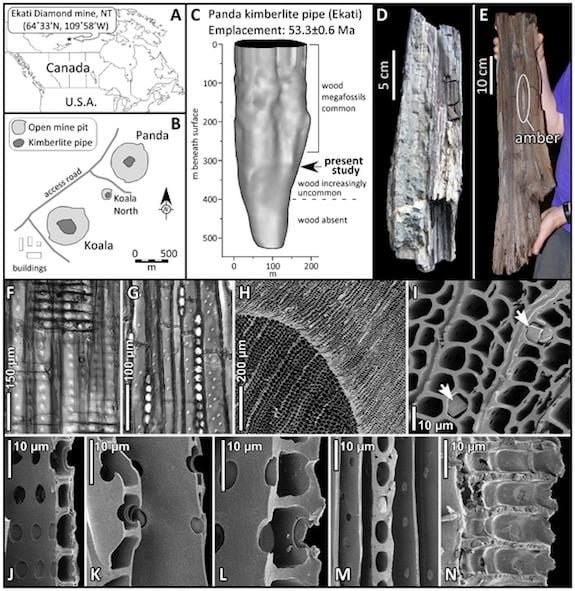

A column of magma had worked its way up from the mantle and drilled its way to the surface, bedazzling itself with diamonds that it picked up along the way. It reached the surface in an explosion that blew up the tree’s happy home and sucked the tree itself (or the bits of it that were left) down 984 feet beneath the surface of the earth before entombing it, along with diamonds in a matrix of kimberlite.

53 million years later, a piece of that tree was recovered from that carrot-shaped deposit in remarkable condition. A group of geologists described the find in a study published in PLoS ONE. There was enough of the tree left, including beautifully preserved cell walls, for the scientists to determine that it was a type of tree called a metasequoia.

The piece of wood also contained amber (fossilized tree resin), and, even more exciting, cellulose. The authors believe that it is the “oldest verified instance of α-cellulose preservation to date,” which is pretty incredible, considering how long ago the tree lived (and died).

By looking at the wood, they were able to draw conclusions about the climate that the tree lived in:

“In the Early Eocene, immediately following peak Cenozoic warmth driven by enhanced greenhouse gas forcing , the subarctic latitudes of the Slave Province harbored Metasequoia in forests developed under conditions 12–17°C warmer and four times wetter than at present.”

It makes sense that there would be arctic redwood forests at that period, given that around the same time, there were palm trees in Antarctica. But determining the paleo-climates of the Canadian north is made more difficult by the fact that most of the evidence left in the area has been scraped away by repeated glaciations, making the diamond mines of the northwest precious to geologists in more ways than one.

More from Smithsonian.com:

Ancient Climate Change Meant Antarctica Was Once Covered with Palm Trees

Media Blows Hot Air About Dinosaur Flatulence