Christie’s Is First to Sell Art Made by Artificial Intelligence, But What Does That Mean?

Paris-based art collective Obvious’ ‘Portrait of Edmond Belamy’ sold for $432,500, nearly 45 times its initial estimate

On Thursday, the AI-generated “Portrait of Edmond Belamy” sold for $432,500—some 45 times its estimated value—in a sale trumpeted by Christie’s as the first auction to feature work created by artificial intelligence.

It’s a moment likely to be marked in the timeline of both AI and art history, but what, exactly, does the sale signify? For the AI community, the Verge’s James Vincent writes in the days preceding the bidding war, the auction provoked controversy among those who argued that the humans behind the canvas (a trio of 25-year-olds best known as the Paris-based art collective Obvious) relied heavily on 19-year-old Robbie Barrat’s algorithms yet failed to sufficiently credit him.

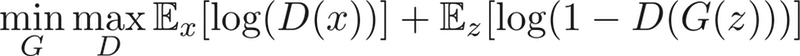

Then again, the entire draw of the otherwise mundane portrait is its attribution to an intimidating mathematical equation:

If the work was truly authored by this string of numbers and letters, does it matter who built and trained the AI? And, given the relatively blurred, imprecise vision the portrait—which Vulture art critic Jerry Saltz scathingly describes as “100 percent generic”—offers of its dour-looking subject, does “Edmond Belamy” even deserve a place in the art history canon?

There are no straightforward answers to these questions. The boundaries between AI, artists and AI-produced art are still amorphous, a fact readily exemplified by the current conflict between Obvious and Barrat. But before diving into the issue at hand, it’s worth revisiting the basics of the technology at the heart of this debate.

Back in August, Hugo Caselles-Dupré, one of Obvious’ three co-founders, outlined the collective’s creative process to Christie’s Jonathan Bastable. As he explained, Edmond and the sprawling network of Belamys depicted in a series of family portraits emerged thanks to a machine-learning algorithm known as the Generative Adversarial Network (GAN). American AI researcher Ian Goodfellow developed GAN in 2014, and as TIME’s Ciara Nugent notes, the rough French translation of “Goodfellow”—bel ami—provided the inspiration for the fictional family’s name.

Obvious’ GAN consists of two parts: the Generator, which produces images based on a data set of 15,000 portraits painted between the 14th and 20th centuries, and the Discriminator, which attempts to differentiate between manmade and AI-generated works.

“The aim is to fool the Discriminator into thinking that the new images are real-life portraits,” Caselles-Dupré said. “Then we have a result.”

The Verge’s Vincent likens the training process to tricking a bouncer at a club. At first, a drunk individual may not be able to act sober enough to gain entry, but with enough practice, an inebriated person’s performance may convince a bouncer to change their tune.

“The networks know how to copy basic visual patterns, but they don’t have a clue how they fit together,” Vincent writes. “The result is imagery in which boundaries are indistinct, figures melt into one another, and rules of anatomy go out the window.”

Barrat, a recent high school graduate now conducting research at a Stanford University AI research lab, has been at the forefront of this algorithm-powered revolution, which is tentatively termed GANism. In an interview with the Washington Post’s Meagan Flynn, Barrat explains that he started experimenting with the technology two years ago, first training GAN to produce original rap songs based on a set of 6,000 Kanye West lyrics and later expanding to surreal landscapes and nude portraits.

After fine-tuning his code, Barrat uploaded it to the sharing platform GitHub, where it was freely available to aspiring AI artists like Caselles-Dupré and the remaining members of his three-man team, Pierre Fautrel and Gauthier Vernier. GitHub exchanges between Barrat and Obvious further speak to the former’s contributions, with Caselles-Dupré repeatedly asking Barrat to tweak the code.

It’s worth noting, too, that Tom White, a New Zealand-based academic and AI artist, conducted tests designed to compare Barrat’s model with those produced by Obvious. As he tells the Verge, the series of Barrat portraits produced by the analysis look “suspiciously close” to that of Edmond Belamy.

(You can judge for yourself below.)

left: the "AI generated" portrait Christie's is auctioning off right now

— Robbie Barrat (@DrBeef_) October 25, 2018

right: outputs from a neural network I trained and put online *over a year ago*.

Does anyone else care about this? Am I crazy for thinking that they really just used my network and are selling the results? pic.twitter.com/wAdSOe7gwz

Caselles-Dupré readily acknowledges that Obvious drew heavily on Barrat’s work, but he tells the Verge the collective tweaked the algorithm to develop a unique portrait style.

“If you’re just talking about the code, then there is not a big percentage that has been modified,” Caselles-Dupré says. “But if you talk about working on the computer, making it work, there is a lot of effort there.”

Obvious’ borrowed code isn’t the only factor contributing to AI art world ire. As the New York Times’ Gabe Cohn writes, many members of the community find the Belamy portraits wholly underwhelming. Vincent points out that critics have further identified technical shortcomings, including low resolution and smeared textures.

In an interview with Cohn, Mario Klingemann, a German artist who has worked extensively with GANs, likened “Edmond” to a “connect-the-dots children’s painting.”

Speaking separately with the Post’s Flynn, Klingemann added, “It’s horrible art from an aesthetic standpoint. You have to put some work into it to call it art. … You have to put your own handwriting on it, make your own mark with these tools. That takes some learning and work and finding something different to say.”

Still, the debate over authorship barely begins to address larger questions of AI autonomy. Christie’s has been quick to capitalize on the Belamy portrait’s singular status, defining its medium with a heady catch-all description: “generative Adversarial Network print, on canvas, 2018, signed with GAN model loss function in ink by the publisher, from a series of eleven unique images, published by Obvious Art, Paris, with original gilded wood frame.” Obvious itself initially marketed the work as “created by artificial intelligence,” but Caselles-Dupré tells the Verge he now regrets using such definitive language.

Jason Bailey, the digital art blogger behind Artnome, explains why such phrasing is misleading, arguing that “anyone who has worked with AI and art realizes” algorithms are tools, not active collaborators or autonomous agents.

Regardless of Edmond Belamy’s true nature, the Christie’s sale marks a turning point. As a specific example of AI-generated art, it isn’t the revolution of Marcel Duchamp’s “Fountain”—an actual urinal turned on its side that sparked the rise of modern and conceptual art—but the kind of work the painting (if you can call it that) represents certainly points to a departure from traditional definitions of art. And, judging by the hefty price tag seen at yesterday’s auction, collectors with large pockets, at least, certainly seem ready to embrace the burgeoning field of AI-led art.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/eb/3c/eb3cf811-df19-4018-9c71-90d78bb7c7d9/edmond.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)