Celebrating a Century of Women’s Contributions to Comics and Cartoons

A new exhibit marking the 100th anniversary of the passage of the 19th Amendment features innovative illustrations from the suffragist movement to today

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8d/ea/8dea867f-972e-4c0a-93e2-6e67b50a7fee/nina_e_allender_at_desk.jpg)

Nina Allender saw herself as a painter. But after women’s rights activist Alice Paul visited her in 1913, she shifted focus, beginning a lengthy tenure as a cartoonist for the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage’s flagship publication, The Suffragist. The painter-turned-cartoonist’s creations depicted suffragists as stylish young women patiently waiting for their rights—a portrayal starkly contrasted by anti-suffrage cartoons that caricatured activists as frumpy and nagging. Allender’s work was instrumental in building public support for the 19th Amendment, which banned voting discrimination on the basis of sex upon its ratification in August 1920.

To commemorate the centennial of this landmark event, Ohio State University’s Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum is hosting an exhibition titled “Ladies First: A Century of Women’s Innovations in Comics and Cartoon Art.” Per the museum’s website, the show draws on the experiences of the many female artists who have shaped the genre to trace its evolution from political cartoons to newspaper comic strips, underground “comix” and graphic novels.

“Part of our goal was to really look at how women were pushing comics and cartoon art forward, not just the fact that women made comics,” exhibition co-curator Rachel Miller tells Columbus Alive’s Joel Oliphint. “We wanted to think about, ‘What are the different ways in which this medium has benefited from women who are making comics?’”

The Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum houses the world’s “largest collection of materials related to cartoons and comics,” including 300,000 original cartoons and 2.5 million comic strip clippings and newspaper pages. “Ladies First” showcases dozens of women whose comics and cartooning influenced both their industry and American life.

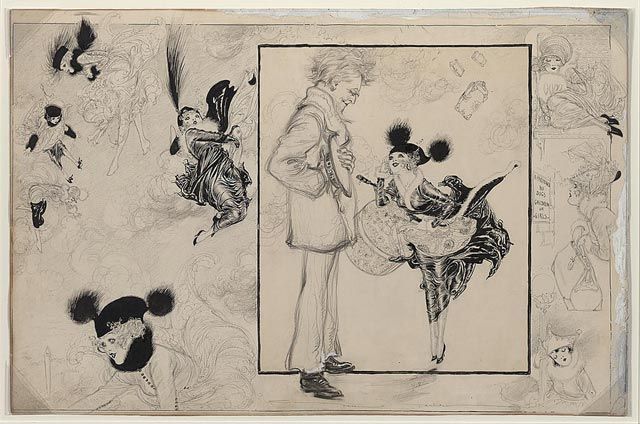

Allender and Edwina Dumm, the first woman to work full-time as a political cartoonist, are among the earliest artists featured in the exhibit. Another near-contemporary, newspaper illustrator Nell Brinkley, challenged how the country imagined modern women, replacing prim and proper figures with independent, fun-loving ones.

The artist’s illustrations were “so popular that … there were even Nell Brinkley hair wavers that were licensed and made all over the country, that young women could buy and style their hair like her cartoon characters,” says co-curator Caitlin McGurk to WCBE’s Alison Holm.

During the 1940s, Jackie Ormes became the first African-American woman cartoonist to have her work distributed nationally. She even licensed a line of upscale dolls modeled on Patty-Jo, one of the two African-American sisters featured in her “Patty-Jo ‘n’ Ginger” comic strip. Rose O’Neill’s “Kewpie” character, meanwhile, was internationally recognized before Disney’s Mickey Mouse. Still, Holm writes, most female cartoonists worked under male pseudonyms until the 1950s.

Around this time, “A group of women cartoonists got together and wrote to the National Cartoonists Society, which was the only and very large at that point professional society for cartoonists, demanding that the National Cartoonists Society either change their name to the National Men’s Cartoonist Society or finally allow women in,” McGurk tells Holm. “And after that moment, they opened their membership up to women and things really began to change.”

“Ladies First” also highlights more recent work, including mainstream comics like Tarpe Mills’ Miss Fury, underground publications such as Wimmen’s Comix and Twisted Sisters, and self-published minicomics. Contemporary comics centered on non-fiction personal narratives—for instance, Alison Bechdel’s “Dykes to Watch Out For” and Raina Telgemeier’s “Smile”—also appear in the show.

“The underground and alternative comics eras and generations are the reason that we have graphic novels the way we know them to be, which are largely a lot of personal stories,” McGurk says to Columbus Alive. “They’re not what old comics were at all, and a lot of these women were a big part in ushering in the autobiographical side of that.”

“Ladies First: A Century of Women’s Innovations in Comics And Cartoon Art” is on view at the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum from November 2, 2019, through May 3, 2020.