As “Dord” Shows, Being in the Dictionary Doesn’t Always Mean Something’s a Word

Even dictionaries can make mistakes, although Merriam-Webster maintains this is their only one

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/35/0b/350bcd76-1b0e-482f-bf83-d8d6b7c70a43/istock-491264114.jpg)

Dord.

Sounds made-up, right? It is. And on this day in 1939, a suspicious editor of Webster’s New International Dictionary, second edition, thought just that after finding it in the dictionary. He went looking for its origins. When he found that the word had none, it was panic at the dictionary office.

Among lexicographers, this incident is famous. The dictionary’s second edition was printed in 1934, writes rumor-debunking site Snopes, and due to a series of editing and printing errors it contained the word dord, defined as a synonym for density used by physicists and chemists. That word appeared on “between the entries for Dorcopsis (a type of small kangaroo) and doré (golden in color.)”

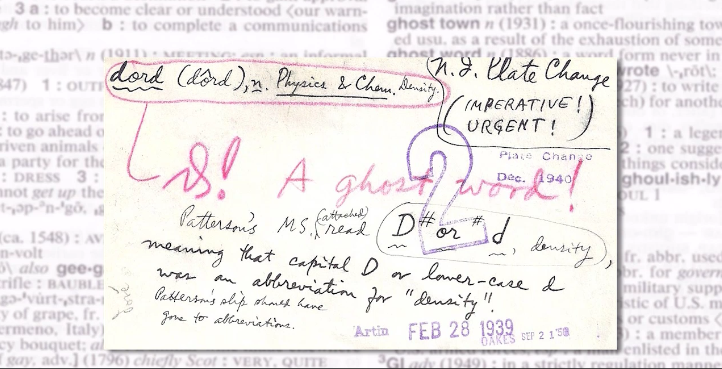

This spooky apparition is known among lexicographers as a “ghost word.” It didn't exist, but there it was, on page 771 of the dictionary. And there it stayed until 1939, when an editor figured out what was happening and wrote this note declaring dord to be “&! A ghost word!” ("&!" is presumably a proofreader's mark, not polite cursing.)

“But for some reason, the change wasn’t actually made until 1947,” says Merriam-Webster’s Emily Brewster in a video. Subsequent dictionaries didn’t contain the word, but like any good ghost, “it continued to rematerialize in the dictionaries of careless compilers for years afterwards,” according to Snopes.

Prior to the existence of the internet, the dictionary was the final arbiter of what did or did not constitute a word. From one perspective, the web has changed this by introducing a culture where errors are tolerated and spelling and grammar don’t matter as much. But then again, the internet’s effect on English (one of its dominant languages) has been, in the words of one linguist, to “increase the expressive richness of language, providing the language with a new set of communicative dimensions that haven’t existed in the past.” And many of the internet’s words make it back to the dictionary, like meme, NSFW and jegging.

What sets these words apart from dord is that they have an origin story and they’ve been used as words: in other words, an etymology. No physicist or chemist had ever used dord, but NSFW is used all the time.

Dictionary-making is serious work. A lot of people have to fail at their jobs for dord to make it in: the writer, the etymolygist, the proofreader. But in fairness to them, a lot of legitimate words do sound made-up. Taradiddle, widdershins and dipthong are just three of the most well-known on a Merriam-Webster list of weird words. Some are esoteric but still used—like taradiddle, which the list notes was recently used by J.K. Rowling but saw more play in the work of Gilbert and Sullivan, Honoré de Balzac and G.K. Chesterton. Others, like widdershins, came to English from another language, in this case German. And some, like dipthong, are technical terms.

Still: dord.