Archaeologists Found a Hand-Dug Holocaust Escape Tunnel

The tunnel was dug by desperate prisoners using spoons

Before the Second World War, Lithuania had 160,000 Jews. But during the Holocaust, an estimated 90 percent of them were murdered—many in places like Ponar, where up to 100,000 Jews were massacred and flung into open graves. Now, writes Nicholas St. Fleur for The New York Times, modern technology has laid one of the secrets of Ponar bare: a hand-dug escape tunnel that was long thought to be only a rumor.

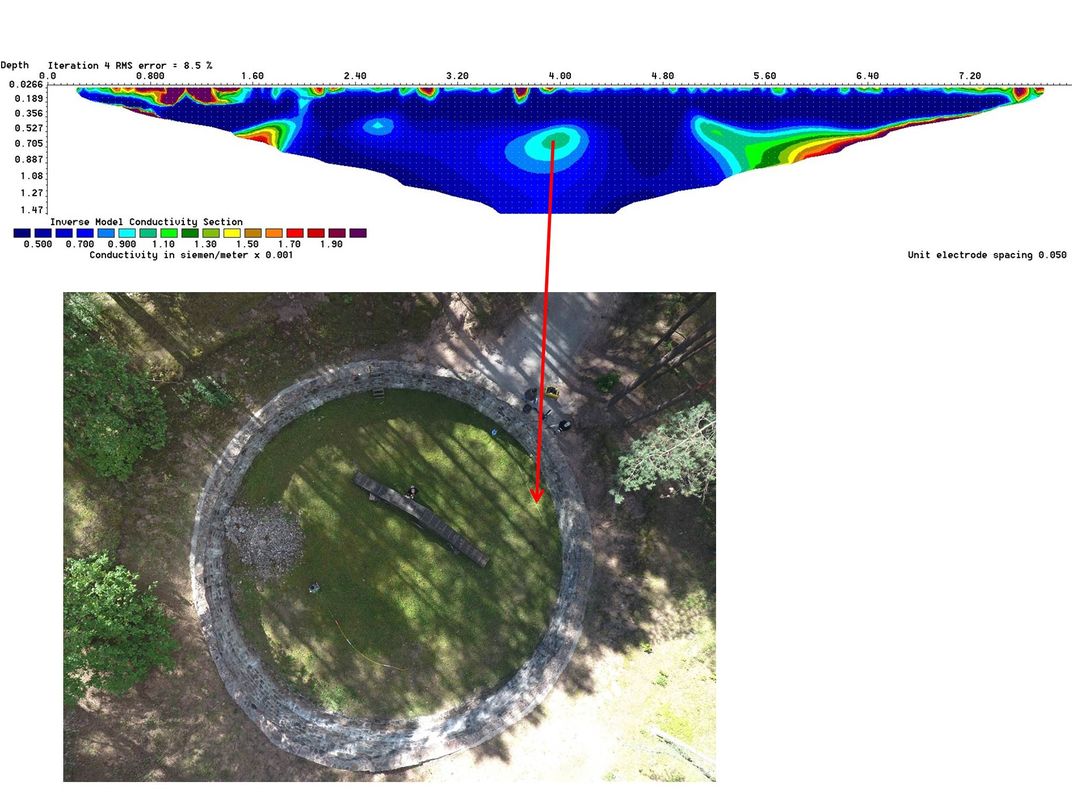

The tunnel was uncovered by archaeologists using ground-penetrating radar (GPR) and electrical resistivity tomography (ERT), both of which lay bare the secrets beneath the surface of the ground. St. Feuer reports that the tools were used to avoid disturbing the thousands of human remains in what was once a gigantic burial pit at Ponar. Both tools revealed something astonishing: a 100-foot-long escape tunnel dug by hand by about 80 prisoners bent on escape.

NOVA will air details on the find in a documentary next year, as Julia Davis reports for NovaNext. While memories of the attempted escape were passed down orally over the years, nobody knew exactly where the tunnel might be until now. With the help of GPR and ERT, Richard Freund, a historian who has led multiple archaeological projects focused on Jewish history, led a noninvasive virtual excavation that revealed a map of the subsurface. Underneath, the team discovered the bodies of people who had died while digging the tunnel, their corpses still clutching the spoons they used to attempt to flee. (Click here to view exclusive video of the find on NovaNext.)

St. Fleur writes that the prisoners who dug the tunnel were forced by Nazis to cover up signs of the mass extermination that took place at Ponar by exhuming and burning bodies from the pits where they had been thrown. They took advantage of the opportunity to dig the tunnel. In 1944, 80 prisoners attempted to escape through the tunnel; 12 succeeded and of those, 11 survived the remainder of the war.

Mass graves were all too common during the Holocaust—as Cornelia Rabitz reports for Deutsche Welle, historians and archaeologists are racing to uncover as many as possible while survivors still live. The team at Ponar didn’t just uncover signs of life; they also discovered previously unknown burial pits containing the ashes and bodies of even more victims. Perhaps with the help of new technologies like those used at Ponar, historians can gain an even clearer picture of the horrors of the Holocaust in Europe—and of the passion that drove victims to survive.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erin.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erin.png)