Newly Documented Aboriginal Rock Art Is ‘Unlike Anything Seen Before’

The ancient paintings depict close relationships between humans and animals

:focal(959x461:960x462)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/af/fc/affcb649-e9d4-4417-9aaf-6f3c7f8a3aec/rock_art_1.jpeg)

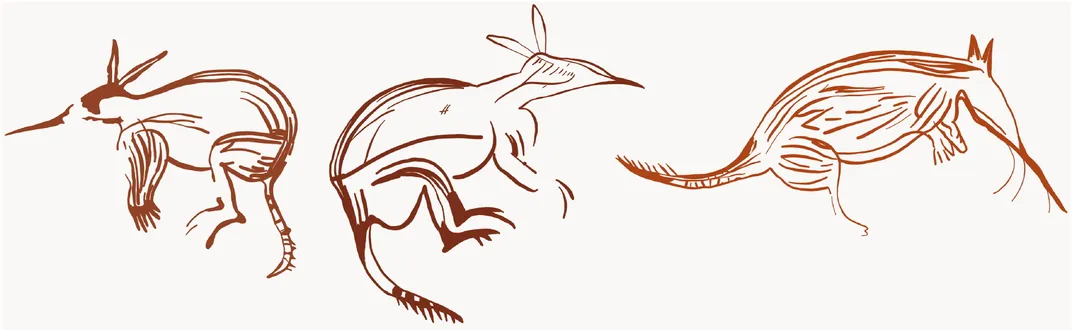

Kangaroos and wallabies mingle with humans, or sit facing forward as if playing the piano. Humans wear headdresses in a variety of styles and are frequently seen holding snakes. These are some of the scenes included in hundreds of newly documented rock paintings found in Australia’s Arnhem Land region.

“We came across some curious paintings that are unlike anything we’d seen before,” Paul S.C. Taçon, chair of rock art research at Griffith University and lead author of a study recently published in the journal Australian Archaeology, tells BBC News’ Isabelle Rodd.

Collaborating closely with the area’s Aboriginal communities over more than a decade, the researchers recorded 572 paintings at 87 sites across an 80-mile area in the far north of Australia, write Taçon and co-author Sally K. May in the Conversation. The area is home to many styles of Aboriginal art from different time periods.

Co-author Ronald Lamilami, a senior traditional landowner and Namunidjbuk elder, named the artworks the “Maliwawa Figures” in reference to a part of the clan estate where many were found. As the team notes in the paper, Maliwawa is a word in the Aboriginal Mawng language.

Most of the red-hued, naturalistic drawings are more than 2.5 feet tall; some are actually life-size. Dated to between 6,000 and 9,400 years ago, many depict relationships between humans and animals—particularly kangaroos and wallabies. In some, the animals appear to be participating in or watching human activities.

“Such scenes are rare in early rock art, not just in Australia but worldwide,” explain Taçon and May in the Conversation. “They provide a remarkable glimpse into past Aboriginal life and cultural beliefs.”

Taçon tells Genelle Weule of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) that the art appears to be a “missing link” between two styles of Aboriginal art found in the area: dynamic figures and X-ray paintings.

Artists created the former, which show subjects in motion, around 12,000 years ago. Like dynamic figures, the Maliwawa art often shows individuals in ceremonial headdresses—but the people and animals portrayed are more likely to be standing still.

The newly detailed works also share some features with X-ray paintings, which first appeared around 4,000 years ago. This artistic style used fine lines and multiple colors to show details, particularly of internal organs and bone structures, according to the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

In addition to offering insights on the region’s cultural and artistic development, the figures also hold clues to changes in the area’s landscape and ecosystems. The archaeologists were particularly interested in pictures that appear to depict bilbies, or small, burrowing marsupials.

“Bilbies are not known from Arnhem Land in historic times but we think these paintings are between 6,000 and 9,400 years of age,” Taçon tells the ABC. “At that time the coast was much further north, the climate was more arid and ... like what it is now in the south where bilbies still exist.”

This shift in climate occurred around the time the Maliwala Figures were made, the researcher tells BBC News.

He adds, “There was global warming, sea levels rising, so it was a period of change for these people. And rock art may be associated with telling some of the stories of change and also trying to come to grip with it.”

The art also includes the earliest known image of a dugong, or manatee-like marine mammal.

“It indicates a Maliwawa artist visited the coast, but the lack of other saltwater fauna may suggest this was not a frequent occurrence,” May tells Cosmos magazine’s Amelia Nichele.

Per Cosmos, animals feature heavily in much of the art. Whereas 89 percent of known dynamic figures are human, only 42 percent of the Maliwawa Figures depict people.

Rock art has been a central part of Aboriginal spiritual and educational practices for thousands of years—and still is today. Important artwork is often found in spiritually significant locations. Much of the art tells stories, which can be interpreted at different levels for children and for initiated adults.

Australians, write Taçon and May for the Conversation, are “spoiled with rock art.” (As many as 100,000 such sites are scattered across the country.) Still, the co-authors argue, rock art’s ubiquity shouldn’t lead anyone to dismiss the significance of an entirely new artistic style.

“What if the Maliwawa Figures were in France?” the researchers ask. “Surely, they would be the subject of national pride with different levels of government working together to ensure their protection and researchers endeavoring to better understand and protect them. We must not allow Australia’s abundance of rock art to lead to a national ambivalence towards its appreciation and protection.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Livia_lg_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b8/65/b865d6a9-bbc1-44ec-9f4b-8b885aa6c83b/rock_art_3a.jpeg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/1f/cb/1fcb93f3-090b-4f33-8909-fb5981250b1c/244466_web.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/04/53/045374c5-b2d6-4f1d-b914-a60dde1f5d3b/244467_web.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Livia_lg_thumbnail.png)