A Sickly Paleolithic Pupper Only Survived Because of Human Help

The canine wouldn’t have been a good hunter, hinting early humans may have loved their pets for more than athleticism

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/82/c0/82c0a33f-92ae-4b20-aaa1-44c193ce553b/istock-830930102.jpg)

In 1914, stone quarry workers in the German suburb of Oberkassel unearthed the 14,000-year-old remains of a man, a woman and a dog. The humans appeared to have been deliberately buried with their canine companion, making the grave one of the earliest known examples of dogs’ domestication. As Laura Geggel reports for Live Science, recent re-examination of the dog bones indicate that the pup had fallen very ill and likely received care, suggesting that the emotional bond between dogs and humans stretches back to the Paleolithic era.

The new study, published in the Journal of Archaeological Science, was led by Luc Janssens, a veterinarian and PhD candidate at Leiden University in the Netherlands. His analysis of the bones revealed that not one, but two dogs had been buried at the Oberkassel site—a “late juvenile” and an older canine, according to the study.

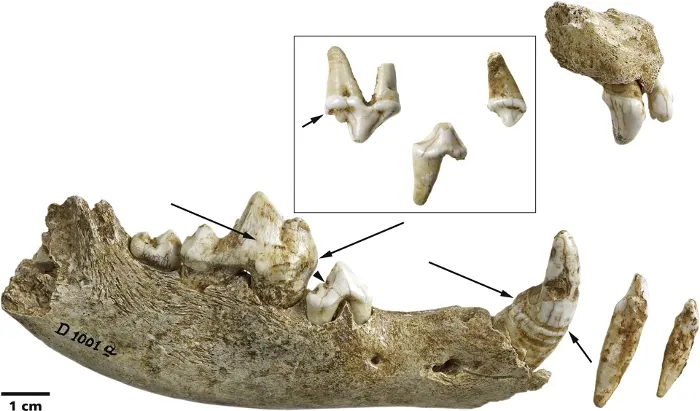

The younger dog was around 27 weeks old at the time of its burial. When Janssens examined the puppy’s teeth, he found evidence of a serious morbillivirus infection. Also known as canine distemper, the virus affects dogs’ respiratory, gastrointestinal and nervous systems. Symptoms begin with fevers, diarrhea and vomiting, and can progress to the point of seizures and paralysis. “Without adequate care, a dog with a serious case of distemper will die in less than three weeks,” Janssens says in a statement.

But the Oberkassel puppy didn’t die within that time frame. It appears to have contracted the virus at around three or four months and suffered two or three periods of illness that each lasted up to six weeks. According to Janssens and his team, it would not have been possible for the ailing pooch to live that long without receiving care from humans. “This would have consisted of keeping the dog warm and clean (diarrhea, urine, vomit, saliva), certainly giving water and possibly food,” the study authors write.

As Mary Bates notes in National Geographic, it is not entirely clear when humans began to domesticate dogs—or why. Most theories suggest that our ancestors used the animals for tasks like hunting and herding.

The new analysis of the Oberkassel bones, however, suggests that there was more nuance to the relationship between Paleolithic humans and their dogs. A gravely ill puppy like the one found in the grave would have been no use as a working animal. “This, together with the fact that the dogs were buried with people who we may assume were their owners, suggests that there was a unique relationship of care between humans and dogs,” Janssens says in the statement.

It seems possible, in other words, that dog has been man’s best friend for a very, very long time.