127-Million-Year-Old Baby Bird Fossil Offers Peek Into Ancient Avian Development

The baby enantiornithe had a soft sternum and likely could not fly

:focal(565x449:566x450)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/dd/06/dd06c384-2d1a-46f1-bf9a-ec41232c5862/1920_reconstruction.jpg)

Back when dinosaurs roamed the Earth, a sub-class of birds known as enantiornithes soared through the skies. These ancient avians differed from living birds in several key ways; they had teeth, for one, and clawed fingers protruding from each wing. Now, as Helen Briggs reports for the BBC, new analysis of an exceptionally rare baby enantiornithe fossil is revealing new details about how the prehistoric birds developed.

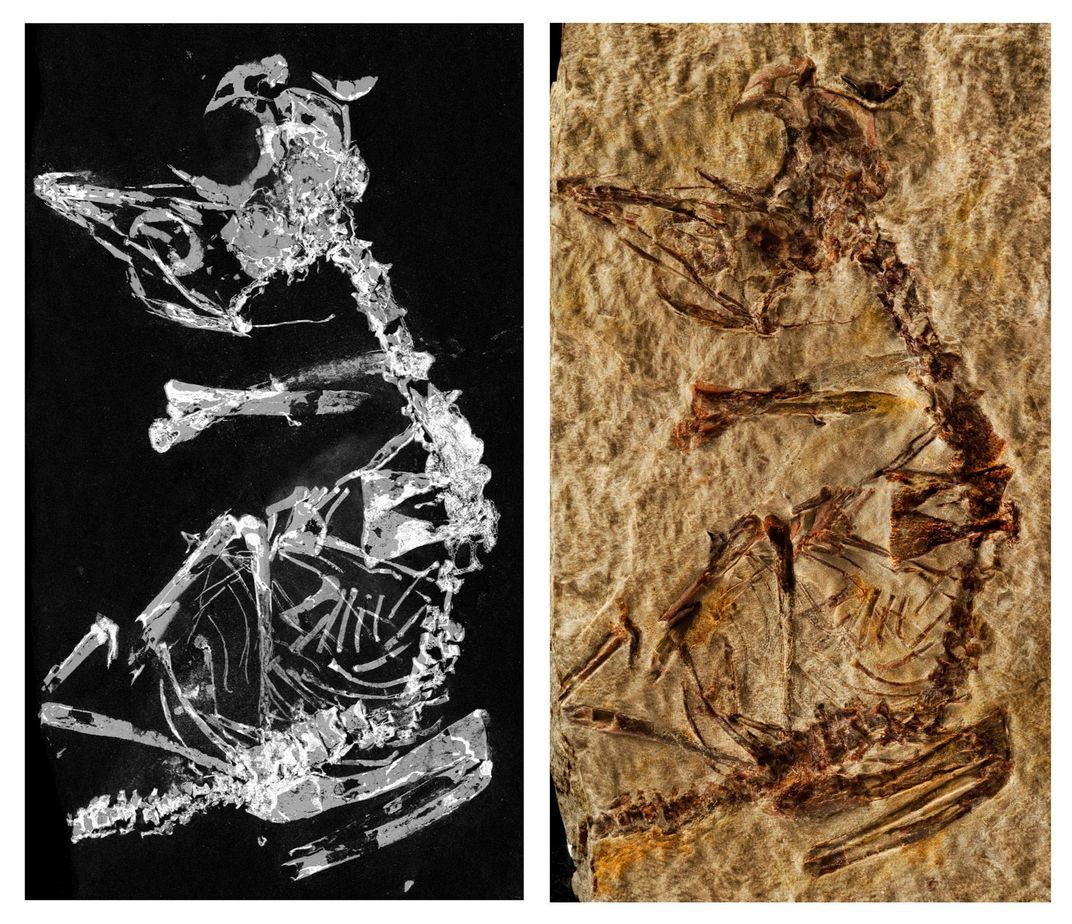

The fossil was discovered “many years ago” at Las Hoyas, a paleontological site in Spain, Briggs writes. But the 127-million-year-old fossil was largely unstudied until recently, when an international team of researchers decided to re-examine the relic using a synchotron, or particle accelerator that can shine very bright light on a fossil, allowing scientists to study it in minute detail.

Researchers are particularly interested in the Las Hoyas fossil because it preserves a baby bird that appears to have died not long after its birth. Describing their analysis in the journal Nature Communications, the researchers note that by studying the bird’s ossification, or bone development, they can gain important insights into its evolution.

“The evolutionary diversification of birds has resulted in a wide range of hatchling developmental strategies and important differences in their growth rates,” Fabien Knoll, a senior research fellow at the University of Manchester and lead author of the new study, explains in a statement. “By analyzing bone development we can look at a whole host of evolutionary traits.”

At the time of its death, the little enantiornithe was less than two inches long—smaller than the average human’s little finger, the statement notes. The bird weighed just 0.3 ounces when it was alive. Researchers were also able to see that the chick’s sternum, or breastbone, was largely made of cartilage and had not hardened into solid bone. This, the team writes in the study, hints that the little critter likely couldn't fly.

Because of its limited flying abilities, the baby bird was probably highly reliant on its parents for care and feeding, but this is not a foregone conclusion. Modern bird species exist on a spectrum that ranges from “altricial,” which describes birds that are unable to move after birth and are completely reliant on their parents, to “precocial,” which refers to critters that hatch with feathers and are able to leave the nest after two days. As the study authors note, “semi-precocial and many precocial species are able to walk at an early age, but are unable to fly until almost fully grown.” The baby enantiornithe, in other words, may have been able to get around even though it couldn’t fly.

Intriguingly, as Laura Geggel of Live Science notes, the patterns of ossification observed in the Las Hoyas fossil are different from those seen in among other baby enantiornithines. This in turn suggests that the birds “may have been more diverse than previously thought,” the study authors write.

Enantiornithes do not have any living descendants; the birds we know today evolved from a group of small, carnivorous dinosaurs known as maniraptoran theropods. But parallels exist between modern birds and ancient enantiornithes. In 2016, an analysis of wings preserved in amber, which most likely belonged to a juvenile enantiornithe, revealed that the bird’s feathers were similar in arrangement and microstructure to the feathers of living avians. And the new study suggests that baby enantiornithes may have developed in a similar way to their modern cousins.

“This new discovery, together with others from around the world, allows us to peek into the world of ancient birds that lived during the age of dinosaurs,” Luis Chiappe, directors of the Dinosaur Institute at the LA Museum of Natural History and the study’s co-author, said in the University of Manchester statement. “It is amazing to realize how many of the features we see among living birds had already been developed more than 100 million years ago.”